By: Ikram Mezghani

Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) is not a condition most people expect to encounter outside the pages of a neurology textbook. Globally, it is considered rare, affecting only one to two people out of every 100,000 per year. However, in August of this year, news reports began emerging from Gaza where doctors described an alarming rise in GBS cases among children.

In the report from the World Health Organization, one terrified patient’s mother described her normally-playful son, Waleed Ghalibeh suddenly unable to move his limbs (Figure 1). Within hours, he lost the ability to speak or swallow, his lower jaw paralyzed, and his eyes remained open, tearful, unable to blink. For days he suffered, until he was brought to Al-Aqsa Hospital, one of the only hospitals still in operation in Gaza. His lungs had failed, and he was placed on a ventilator for seventeen days, where doctors diagnosed him with GBS. Reading about Waleed made me want to understand the illness that had stolen his ability to walk, the impact of the ongoing genocide in Gaza on patients like him, and how we, as members of the scientific and healthcare communities, can more effectively advocate for and support those who are oppressed.

Understanding Guillain-Barré Syndrome

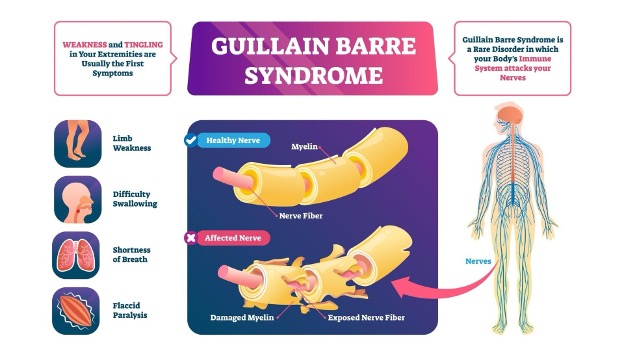

GBS is a rare autoimmune disorder in which the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks its own peripheral nerves, or the nerves that are responsible for motor control and sensation. GBS often develops after an infection, most commonly gastrointestinal or respiratory. Infectious agents such as Campylobacter jejuni, enteroviruses, Epstein-Barr virus, influenza, and Zika virus are well-known triggers, particularly in individuals with weaker immune systems3. Other factors like malnutrition and deficiencies in key nutrients, including iron, folate, vitamin B12, and zinc, can make the body more vulnerable by weakening immune defenses and slowing nerve repair4. The prolonged destruction in Gaza, combined with the ongoing blockade, has severely exacerbated both infectious disease spread and nutrient deficiencies, likely contributing to the stark rise in GBS and influencing the severity of its neurological effects, as seen in Waleed’s sobering case.

Normally, the immune system fights infections by targeting foreign germs such as bacteria or viruses. In GBS, however, some of these infections can trigger a process called molecular mimicry, where the immune system mistakes parts of the body’s own nerve cells for the invading germs1. This causes antibodies and immune cells to attack the nerves, leading to the autoimmune damage characteristic of GBS.

One key target of this attack is the myelin sheath, an insulating layer of fatty material that wraps peripheral nerves and facilitates rapid transmission of electrical signals between the brain and the rest of the body, like conductive armor2 (Figure 2). The degradation of the protective myelin sheath causes disruption in nerve signaling and can result in muscle weakness, tingling, changes in sensation, and, in severe cases, paralysis.

How Does the Immune Response to GBS Work?

Several types of immune cells drive the autoimmune response in GBS5. It begins with B-cells producing antibodies that mistakenly bind to gangliosides, complex sugar-lipids found on the surface of nerve cells that play a role in communication and cell signaling (Figure 3). The antibodies flag these nerve cells for attack, marking them for the immune system to recruit cells such as neutrophils, which release cytokines, chemicals that trigger inflammation. The cytokines then signal for macrophage recruitment, which attack and physically engulf and degrade the myelin sheath surrounding the nerves.

Other immune components, such as proteins from the complement system – a part of the immune system made up of blood proteins that boost the effects of antibodies – join the site. These proteins act like amplifiers, increasing inflammation and, in some cases, punching holes in cell membranes, which damages the nerves and the protective myelin sheath. In turn, this slows or completely blocks signal transmission of the nerves.

Symptoms and Diagnosis

Symptoms of GBS vary in severity and can progress rapidly over hours, days, or weeks. Early signs often include tingling or numbness in the hands and feet and weakness in the lower legs. Weakness can ascend to the arms, chest, and face, potentially leading to paralysis. If respiratory muscles are affected, patients may require mechanical ventilation or other interventions, like in Waleed’s case.

Diagnosing GBS requires a combination of careful clinical evaluation and specialized tests. Nerve conduction studies, for instance, can reveal slowed or blocked electrical signals along the peripheral nerves. A lumbar puncture may detect abnormal changes in the cerebrospinal fluid, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can help rule out other conditions that can present with similar symptoms as GBS such as tick paralysis, poliomyelitis, systemic vasculitis, lead poisoning, and botulism. However, amid the systemic destruction of Gaza’s healthcare system and the deliberate targeting of its medical workers, which has rendered most hospitals inoperative, access to such tests is nearly impossible. For patients like Waleed, delayed diagnosis means enduring devastating and irreversible consequences that could have been prevented with early diagnosis.

Treatment and Rehabilitation

There is no cure for GBS. However, early treatment is effective when started within two weeks of symptom onset and can reduce symptom severity, halt disease progression, and support recovery.

Two primary therapies are used: intravenous immunoglobulin, which provides a concentrated pool of antibodies that help neutralize the immune system’s attack on peripheral nerves, and plasma exchange, which removes harmful antibodies from the bloodstream that are damaging the nerves. Both therapies aim to modulate the immune response and prevent further nerve injury.

Alongside these interventions, supportive care is essential throughout the disease course. Physiotherapy helps preserve joint mobility, prevent contractures, and maintain muscle strength. As recovery progresses, physiotherapists guide patients through endurance and functional exercises to promote independence in daily activities. Assistive devices, such as leg braces or wheelchairs, may be recommended to support mobility and safety during rehabilitation. In addition, respiratory support, including mechanical ventilation if breathing muscles are affected, ensures adequate oxygenation. Nutritional support is also critical to maintain overall health and facilitate recovery, especially when prolonged weakness or paralysis limits mobility and self-care. By combining both acute and supportive care, long-term disability can be minimized with maximized functional recovery in patients affected by GBS.

However, in Gaza, these treatments are virtually inaccessible. The blockade, hospital bombardments, and severe shortages of medical supplies and electricity have made treatments nearly impossible to provide to patients like Waleed, leading to devastating, lifelong disabilities.

Science and Medicine Alone Cannot Heal

Waleed’s heartbreaking story and the rise in prevalence of once-rare Guillain-Barré in Gaza captures the cruel reality of medicine in an ongoing genocide: when a combination of politics, blockade, and starvation strip a population of the most basic tools of care, illnesses that are treatable elsewhere become life-threatening emergencies. The most straightforward “treatment” to this danger, of course, would be a stop to the genocide itself. If children had access to adequate nutrition, clean water, functioning hospitals, and uninterrupted medical supplies, cases like Waleed’s could be managed successfully. Instead, systemic violence and neglect create preventable suffering. This intersection of medicine and human rights underscores an urgent truth: science alone cannot protect life when political forces are at work, conspiring to deny access to basic tools of health.

As a scientist and an activist, I choose to advocate not only for treatment of life-threatening illnesses, but for the complete cessation of the conditions that make such preventable conditions possible. If you feel motivated to do the same, I encourage you to seek out local resources in your community, forge community connections, speak out, act, and make a difference.

TL; DR

- GBS is a rare autoimmune disorder where the immune system attacks the peripheral nerves, damaging the myelin sheath.

- GBS has become a public-health emergency in Gaza due to the ongoing genocide, blockade, and systemic targeting of healthcare workers and infrastructure.

Reference

- Rojas M, Restrepo-Jiménez P, Monsalve DM, Pacheco Y, Acosta-Ampudia Y, Ramírez-Santana C, Leung PSC, Ansari AA, Gershwin ME, Anaya JM. Molecular mimicry and autoimmunity. J Autoimmun. 2018 Dec;95:100-123. Epub 2018 Oct 26. PMID: 30509385.

- Fallon M, Tadi P. Histology, Schwann Cells. [Updated 2023 May 1]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544316/

- Hughes RAC. Guillain-Barré syndrome: History, pathogenesis, treatment, and future directions. Eur J Neurol. 2024 Nov;31(11):e16346. Epub 2024 May 16. PMID: 38752584; PMCID: PMC11464409.

- El Bilbeisi AH. Malnutrition and nutritional deficits as aggravating factors in Guillain-Barré Syndrome: a call for nutritional intervention in the Gaza Strip. Front Public Health. 2025 Sep 24;13:1681063. PMID: 41069834; PMCID: PMC12504248.

- Hughes RAC. Guillain-Barré syndrome: History, pathogenesis, treatment, and future directions. Eur J Neurol. 2024 Nov;31(11):e16346. Epub 2024 May 16. PMID: 38752584; PMCID: PMC11464409.