By Louis Betz

Approximately 80% of the United States population engage in sports and fitness activities. Engaging in athletics provides benefits to physical health, social behavior, and developing soft skills like leadership and teamwork, especially in adolescents and young adults1. Despite the benefits of sports, it is important to identify and minimize potential health risks, especially in contact sports like football and rugby. One of the most common and dangerous injuries in contact sports is concussion, and the accumulation of multiple concussions can lead to irreversible brain damage. Great strides have been made over the past few decades to engineer better helmets, coach player safety, and alter the rules of sports to minimize injuries and hits to the head and neck area. With the significant impact (pun absolutely intended) that sports have on the lives of countless individuals, it is crucial to explore how we continue to make the sports we all love safe and enjoyable for all.

Concussions are directly related to intensity and player on player contact

In contact sports, concussions, also known as mild traumatic brain injuries (mTBI), occur when a blow to the head causes the brain to move within, and possibly collide with, the skull. Concussions are not immediately life threatening; however, they increase the risk for future TBIs, stroke, and broken blood vessels in the brain. Concussions are also associated with an increased risk of memory loss and neurodegeneration, or irreversible death of neurons in the brain.

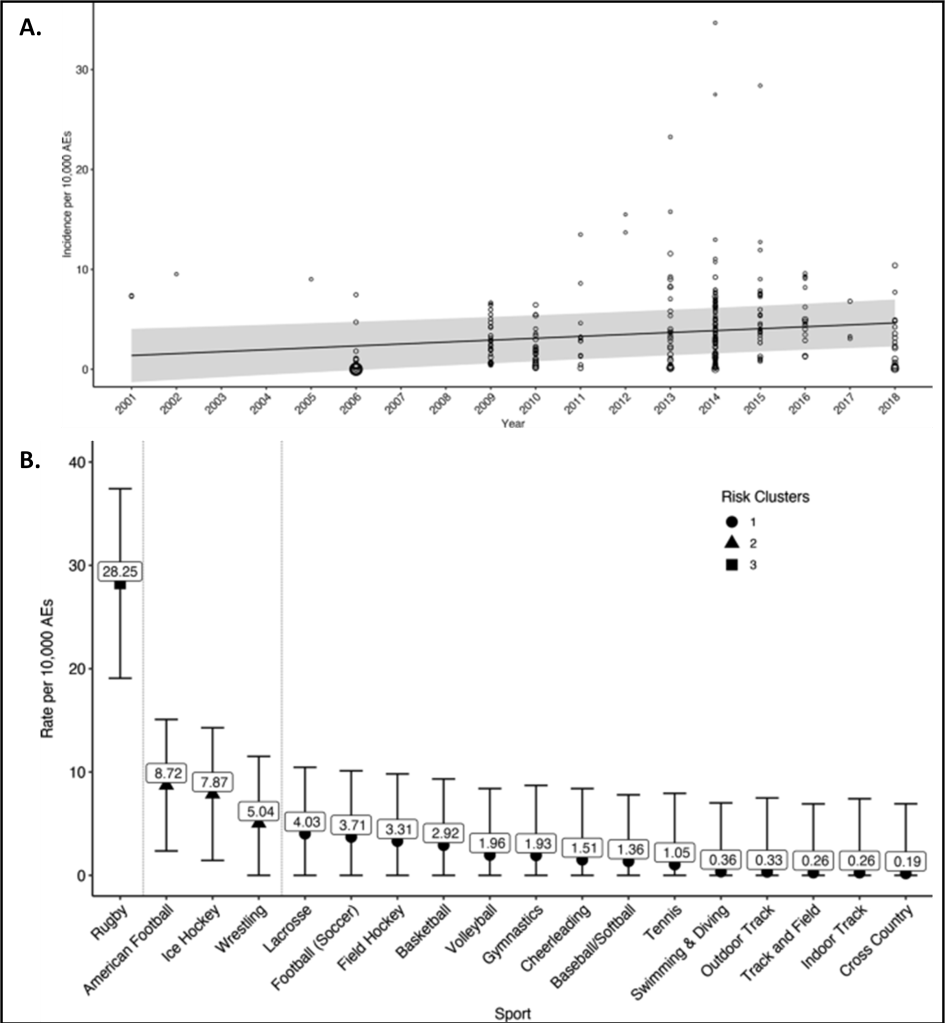

The incidence of concussion diagnoses has risen over the last 20 years (Fig. 1A)2. This increase is most likely due to an increase in awareness of concussions, rather than an actual increase in concussion rate. A recent study performed on high school and collegiate level athletes identified areas of need and the populations most at risk for mTBIs. This study identified the risk of concussion for any athletic event (AE), including games and practices, in 18 of the most popular sports. The top five sports that presented the highest risk for concussion were rugby (28.25 per 10,000 AE), American football (8.72 per 10,000 AE), ice hockey (7.87 per 10,000 AE), wrestling (5.04 per 10,000 AE), and lacrosse (4.03 per 10,000 AE) (Fig. 1B)2. These sports are associated with the highest incidence of concussion because they involve more physical contact between athletes. Rugby carries a much larger risk of concussion compared to all other sports studied, likely because there is no enforcement for helmets or headgear for this sport.

This study also concluded that the incidence of concussion was greater during games rather than during practices across all sports (2.01 more per 10,000 AE), especially for high contact sports like American football (22.3 more per 10,000 AE), rugby (15.4 more per 10,000 AE), ice hockey (16.9 more per 10,000 AE), and lacrosse (9.5 more per 10,000 AE). These findings could be attributed to the fact that athletes tend to play harder and more aggressively during games compared to practices.

Concussions in high contact sports such as rugby, American football, and ice hockey occurred at a similar rate at the high school and collegiate levels. However, collegiate athletes received more concussions than high school athletes in medium contact sports like soccer (1.3 more per 10,000 AE), field hockey (1.54 more per 10,000 AE), and basketball (0.83 more per 10,000 AE)2. Collegiate athletes in medium contact sports may be at a higher risk of concussions compared to their high school counterparts for a few reasons. Athletes tend to be stronger at the collegiate level, they kick harder, throw the ball harder, and hit the ball harder, thus there is an increased risk for a projectile causing a concussion for college athletes compared to high school athletes. Another potential cause for this is that college athletes may play harder and put themselves or others around them in situations of danger. These data suggest that athletes in high intensity scenarios in medium and high contact sports are a vulnerable population for concussions. These populations present the largest need for safer equipment, coaching towards safer play, and rule changes to minimize concussions.

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy

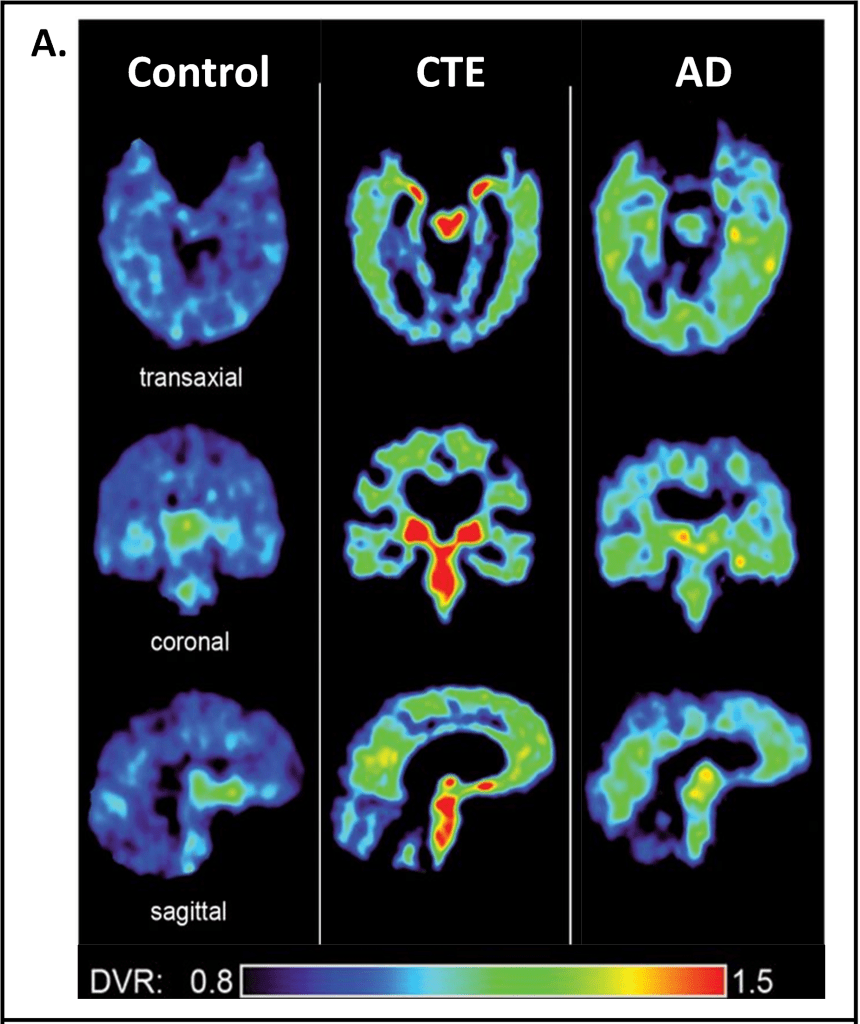

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) is a disease linked to repetitive brain trauma and an accumulation of numerous mTBIs. CTE was first identified postmortem in American football players but has since been diagnosed postmortem in amateur athletes as well. CTE pathology involves phosphorylated tau proteins aggregating around blood vessels, astrocytes (glial cells that support neurons), and cortical gray matter in the brain3,4. Tau is a protein that stabilizes microtubules, which are cytoskeletal proteins that contribute to structural integrity and communication between neurons. When tau is overly phosphorylated (addition of a phosphate group to the molecule causing changes to its function), it no longer binds to microtubules in the neurons, leading to the destabilization and eventual death of neurons5. Phosphorylated tau is implicated in other brain diseases like Alzheimer’s disease and is hypothesized to be a cause of neurodegeneration. Interestingly, the pattern of phosphorylated tau observed in CTE is distinct from that of Alzheimer’s disease, suggesting that CTE has a different etiology (Fig. 2)6. CTE is associated with a range of symptoms, the most common being extreme changes in mood (depression and hopelessness), behavior (extreme impulsiveness and physical/verbal violence), cognitive decline, and impaired motor abilities like gait7.

A shift towards safer equipment

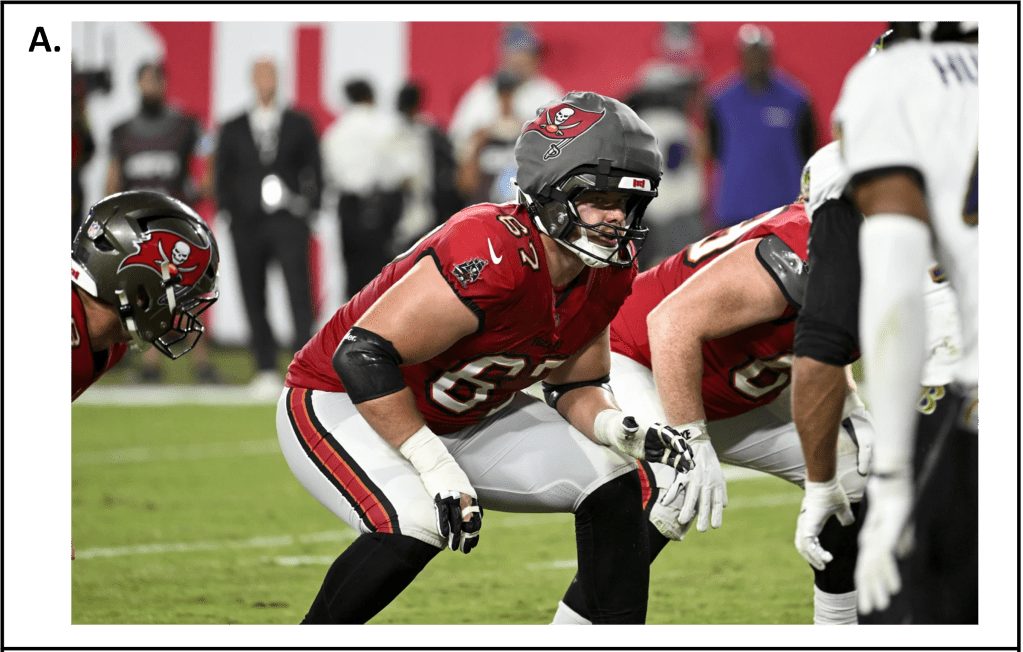

In the United States, football season spans from late August to early February. American football is played at all levels, from the professional National Football League (NFL) to elementary school children in “pee wee” football. If you have been watching NFL or college football this year, you may have noticed players wearing a foam cover on their helmets. These padded football helmet covers are commonly called “Guardian Caps”, after the most popular branded product of the sort. Guardian Caps are the latest development in athletic gear that might protect wearers from concussions and CTE (Fig. 3). The NFL has mandated that all athletes must wear Guardian Caps during practices, and they are optional for games. In college high school, and youth football, Guardian Cap mandates are program-dependent, but players are allowed to wear them during games. The NFL claims that the use of Guardian Caps has reduced the concussion rate 50% during the 2022 and 2023 preseason training camps. However, this data was collected by the NFL and has not been peer reviewed. Two recent studies examined the kinetics of the Guardian Cap, and they found that there is no significant reduction in impact from a hit when wearing a Guardian Cap8,9. While Guardian Caps may not prevent concussions resulting from a massive blow to the head, they may be useful for the small, repetitive hits that chronically contribute to brain injury. Since guardian caps are a new technology, no peer reviewed clinical data is available. We can expect to see more data on the efficacy of these caps in the coming years.

Some NFL players have advocated for Guardian Caps, urging other players to protect themselves from injury. Indianapolis Colts Tight End Kylen Granson stated the following:

“There’s no amount of aesthetic that could outweigh what a TBI (traumatic brain injury) could do to you, and one of the more unknown things is that not only is it the big hits that you have to worry about, it’s the culmination of a bunch of little hits.”

“I want to inspire kids to think that health and safety is also cool. You can do cool things out on the football field and still wear a Guardian Cap. I want my (future) children to wear helmets when they ride a bike. … Because there’s no amount of cool that would be worth walking into a hospital room and your child’s in a vegetative state because they weren’t wearing a helmet. Because they didn’t want to look dumb.”

Although there is no peer reviewed data confirming that Guardian Caps are effective for reducing football-related concussions, the resulting discussions are bringing the concern of concussions to the forefront and prioritizing advancements to make contact sports safer. By furthering the technology in helmet design, athletes will be able to play longer and mitigate the risks of concussion and CTE.

TL;DR

- Concussions are on the rise in medium and high contact sports.

- Repeated concussions can cause chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a progressive degenerative brain disorder.

- Guardian Caps are the newest development for potentially preventing concussions and chronic traumatic encephalopathy in American football players.

Reference

1. Wankel, L. M. & Berger, B. G. The Psychological and Social Benefits of Sport and Physical Activity. J. Leis. Res. 22, 167–182 (1990).

2. Van Pelt, K. L., Puetz, T., Swallow, J., Lapointe, A. P. & Broglio, S. P. Data-Driven Risk Classification of Concussion Rates: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. Auckl. NZ 51, 1227–1244 (2021).

3. Asken, B. M. et al. Factors Influencing Clinical Correlates of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE): a Review. Neuropsychol. Rev. 26, 340–363 (2016).

4. McKee, A. C. et al. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE): criteria for neuropathological diagnosis and relationship to repetitive head impacts. Acta Neuropathol. (Berl.) 145, 371–394 (2023).

5. Mietelska-Porowska, A., et al., Tau protein modifications and interactions: their role in function and dysfunction. Int J Mol Sci, 2014. 15(3): p. 4671-713.

6. Barrio, J. R. et al. In vivo characterization of chronic traumatic encephalopathy using [F-18]FDDNP PET brain imaging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 112, E2039–E2047 (2015).

7. Montenigro, P. H. et al. Clinical subtypes of chronic traumatic encephalopathy: literature review and proposed research diagnostic criteria for traumatic encephalopathy syndrome. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 6, 68 (2014).

8. Sinnott, A. M. et al. Efficacy of Guardian Cap Soft-Shell Padding on Head Impact Kinematics in American Football: Pilot Findings. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 20, 6991 (2023).

9. Quigley, K. G. et al. Preliminary Examination of Guardian Cap Head Impact Kinematics Using Instrumented Mouthguards. J. Athl. Train. 59, 594–599 (2024).