By Coryn Hoffman

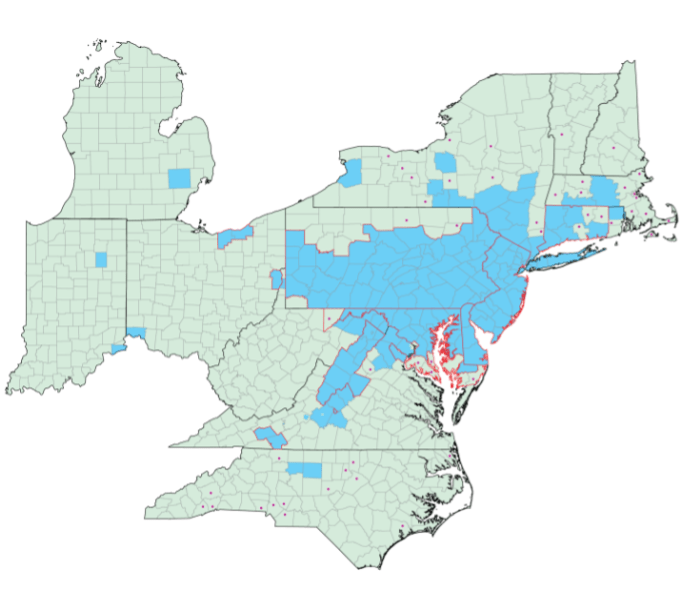

The spotted lanternfly (Lycorma delicatula) is a planthopper that is native to China, India, and Vietnam (Figure 1). These insects have become invasive in northeast America over the past decade, causing significant environmental damage. The first sighting of spotted lanternflies in the United States was in Berks County, Pennsylvania in 2014. These pests can be unintentionally spread across long distances by moving infested materials or items containing egg masses; the first lanternfly populations in North America are thought to have arrived as egg masses on a stone shipment in 20121. By 2021, populations of the spotted lanternfly had spread across the northeast United States with some populations being found as far west as Ohio, Michigan, and Indiana2,3 (Figure 2). Despite efforts to eradicate this pest, its ability to reproduce exponentially and lack of natural predators have made them very difficult to contain.

Environmental Threats

Spotted lanternflies pierce the bark of trees using a “piercing-sucking mouth part” to feed on the sap, much like mosquitos sucking blood from a victim. They also excrete a clear, sticky substance called “honeydew” that coats the trees and allows the growth of a black, sooty mold that decreases photosynthesis. Lanternfly feeding causes trees to lose nutrients that they need to continue growing, causing them to grow more slowly, wilt, and eventually die from the branches inwards toward the trunk in a process known as dieback. This stress makes host plants more susceptible to environmental damage4.

Spotted lanternflies primarily target the Tree-of-Heaven (Ailanthus altissima), an invasive tree brought to North America from China in the 1700s2 (Figure 3). The Tree-of-Heaven is the preferred host, and invasive spread has provided ample habitat for spotted lanternflies. The real problem is that spotted lanternflies also feed on a wide range of economically valuable crops and native plants, including Christmas trees, hardwood trees, walnuts, fruit trees, grapes, and hops. These infestations have had the most notable impact on the lumber industry as well as local vineyards and breweries5. Penn State College of Agricultural Sciences estimates that the economic impact that lanternflies have on agriculture is about $42.6 million per year in Pennsylvania alone6. If lanternflies continue to spread, that number could grow to $324 million annually, presenting a need for more public awareness and effective eradication methods.

The Lifecycle of the Spotted Lanternfly

In order to eradicate the spotted lanternfly, it is important to know how to identify them throughout all developmental stages of their lifecycle, as they look very different at each stage (Figure 4). The first instar stage begins in May-June, when eggs hatch into nymphs, known as instars, that are wingless and black with white spots which will feed on leaves and branches of host trees7.

The second and third instar stages occur between June-July. They do not change in appearance, but they get larger and begin feeding on a variety of trees, moving up and down the tree when they feed. The fourth instar stage begins in July, when they begin to look red and eventually molt and become an adult. They later develop bright red underwings that can be seen when they fly/hop between plants. While the immature nymphs feed on a large range of trees, adult lanternflies only feed on a few species, causing significant damage to these infested host trees7.

In the late summer/early fall, adults begin to mate and females lay eggs on trees, stones, or other outdoor objects. The females lay their eggs in groups and cover them with a white, waxy secretion, creating an egg mass that eventually turns brown and begins to dry up and crack as the eggs hatch the following spring. A single lanternfly lays up to 100 eggs in its lifetime, which easily leads to overpopulation when these insects have no natural predators8.

How can YOU stop the spread?

Spotted lanternflies are easily spread across the country by hitchhiking or laying their egg masses on cars, trucks or trains2,5. If you are traveling through a potentially infested area, you should thoroughly check your vehicles, trailers, and even clothing to prevent accidentally spreading lanternflies or egg masses. Parking with your windows closed and at least 15 feet away from trees, when possible, will also help prevent unintentional transport of the spotted lanternfly3,5.

Spotted lanternfly egg masses are about an inch long and resemble a smear of mud (Figure 5). In addition to vehicles, these egg masses are commonly found on tree trunks and other outdoor objects like lawnmowers, bikes, grills, propane tanks, and outside furniture. If you find an egg mass, destroy it by scraping it into a plastic bag containing hand sanitizer or rubbing alcohol, then zip the bag shut and dispose of it in the trash, making sure to keep it in the alcohol solution3. Furthermore, you should crush nymphs or adult lanternflies if you see them. Their eyes are located on the sides of their head, so if you sneak up on them from the front when you try to stomp on them, they are less likely to jump away.

In addition to crushing the insects, you should inspect trees on your property for infestations. This is best done at dusk, as lanternflies gather in large groups on tree trunks overnight3. In particular, you should remove the Tree-of-Heaven if possible5. An effective method of killing lanternflies is by removing 90% of the Tree-of-Heaven in an area and then keeping the other 10% as “trap trees” that have sticky tree tape around the base (Figure 6). The best time to tape your trees is in early May when the nymphs emerge from egg masses and move up and down tree trunks as they feed9. They become more difficult to trap with the tape in the following stages7.

You should also report infestations and ask for control recommendations in your area. In Pennsylvania, contact the Penn State Extension program. Outside of Pennsylvania, contact your state agricultural department to report infestations outside of quarantined areas5. If you report sightings early, you could help prevent an infestation in a new area.

Current Research

Cornell and Penn State University have been at the forefront of spotted lanternfly research. In collaboration, researchers have identified two types of native fungi, Batkoa major and Beauveria bassiana, that are toxic to these insects but harmless to humans10. When lanternflies encounter these fungal spores, they germinate and colonize the body, killing the fly in a few days. Fungal infection is marked by white fuzz that emerges from the fly’s body a few days after contact, which contains more spores that can infect other insects (Figure 7).

In an experiment at Penn State, areas in Norristown park that had dense populations of both lanternfly nymphs and the Tree-of-Heaven were divided into different plots- control and experimental groups. Using hydraulic sprayers, the control areas were treated with water, while the experimental areas were treated with a commercial biopesticide containing the Beauveria fungus. There were 50% less lanternflies observed in fungus-treated areas, suggesting that it might be an effective way to eradicate this pest. Research on such biopesticides is ongoing to determine its efficacy on adult lanternfly populations and to ensure minimal risk to beneficial insects, such as pollinators. Penn State is also collaborating with researchers from the USDA to study spotted lanternfly biology and behavior as well as new detection and eradication techniques. Officials are also working to help the public understand how citizens can help contain and manage the spread of this invasive insect10.

To learn more about the spotted lanternfly, how to manage infestations, and how to report a sighting, visit the Penn State Extension website at https://extension.psu.edu/spotted-lanternfly.

TL:DR

- The spotted lanternfly is an invasive pest that threatens native plants and agriculture in northeast America.

- You can help stop the spread by:

- Crushing adults and nymphs

- Destroying egg masses

- Placing sticky tape on host trees

- Removing Tree-of-Heaven wherever possible

References

- “Spotted Lanternfly Reported Distribution Map.” Cornell College of Agricultural and Life Sciences. https://cals.cornell.edu/new-york-state-integrated-pest-management/outreach-education/whats-bugging-you/spotted-lanternfly/spotted-lanternfly-reported-distribution-map#:~:text=Spotted%20lanternfly%20(SLF)%2C%20Lycorma,altissima%2C%20or%20Tree%20of%20Heaven.

- Hale, Frank A. “The invasive spotted lanternfly is spreading across the eastern US – here’s what you need to know about this voracious pest.” The Conversation. July 28, 2021. https://theconversation.com/the-invasive-spotted-lanternfly-is-spreading-across-the-eastern-us-heres-what-you-need-to-know-about-this-voracious-pest-162919.

- Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. “Spotted Lanternfly.” U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/resources/pests-diseases/hungry-pests/the-threat/spotted-lanternfly/spotted-lanternfly#:~:text=The%20Spotted%20Lanternfly%20(Lycorma%20delicatula,in%20Pennsylvania%20in%20September%202014.

- “THREAT: SPOTTED LANTERNFLY.” Ohio Department of Natural Resources. https://ohiodnr.gov/discover-and-learn/safety-conservation/about-odnr/forestry/forest-health/insects-diseases/threat-spotted-lantern-fly#:~:text=SLF%20feed%20on%20a%20wide,heaven%2C%20grapes%2C%20and%20hops.

- Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. “Businesses Can Help Stop the Spotted Lanternfly.” U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/resources/pests-diseases/hungry-pests/slfbiz/slf-business-page.

- Schmidt, Maddy. “Could Spotted Lanternflies Be a Good Thing?” Peril & Promise- The Challenge of Climate Change. August 17, 2022.https://www.pbs.org/wnet/peril-and-promise/2022/08/could-spotted-lanternflies-be-a-good-thing/#:~:text=A%20study%20at%20Penn%20State%27s,loss%20of%20about%202%2C800%20jobs.

- “What Is The Spotted Lanternfly Lifecycle?” Spotted Lanternfly Killers. https://spottedlanternflykillers.com/pages/spotted-lanternfly-lifecycle.

- “Spotted Lanternfly.” Penn State Extension. https://extension.psu.edu/spotted-lanternfly-what-to-look-for.

- “Spotted Lanternfly Management.” Cornell College of Agricultural and Life Sciences. https://cals.cornell.edu/new-york-state-integrated-pest-management/outreach-education/whats-bugging-you/spotted-lanternfly/spotted-lanternfly-management

- Duke, Amy. “Organic control of spotted lanternfly is focus of study by Penn State, Cornell.” Penn State University. August 19, 2019. https://www.psu.edu/news/research/story/organic-control-spotted-lanternfly-focus-study-penn-state-cornell/