By Jackson Radler

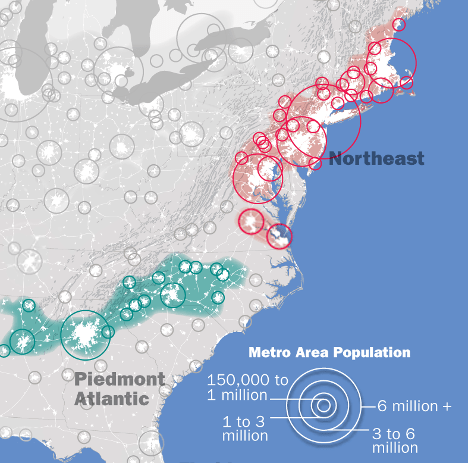

Many major cities in the Northeastern region of the United States, such as New York City and Boston, are ports, and as such are situated directly on the coast. However, as you look farther south, the major metro areas move inland, straying away from the shores of the Atlantic Ocean (Figure 1).

The geographically inclined among you may notice that in the eastern region of the United States, major cities tend to loosely follow the eastern border of the Appalachian Mountains. This makes sense to a certain degree—the tightly packed ridges and valleys of the Appalachians themselves (passing just north of Harrisburg) don’t leave much room for development. But there’s plenty of land between the Appalachians and the coast, especially in the south. Why did settlers time and time again set up shop at the base of these ancient mountains? The answer is due to a combination of geology, rivers, and human nature.

Part 1: Geology

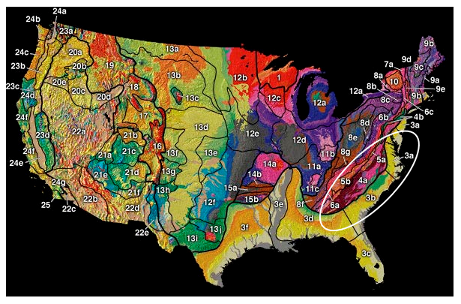

To make sense of the ground we stand on, geologists divide the earth into physiographic regions, provinces, and sections, a hierarchy based on geologic similarity.[1] For example, all areas in Figure 2 labeled with a number 4-10are part of the Appalachian Mountain Region, but 4 and 5 are different provinces within the region. Areas with shared geologic history have often been exposed to similar environments (and thus display similar features), so this becomes a useful tool for comparing large swaths of land.[2] The two provinces relevant to our discussion are the Piedmont (4a in Figure 2) and the Atlantic Coastal Plain (3a-f in Figure 2).

The Piedmont province (region 4a in Figure 2) is a rocky plateau composed of igneous and metamorphic rock, just east of the true ridges-and-valleys of the Appalachians, and runs north-south from the New York harbor to Georgia.[3] The name piedmont is from the Italian, and translates to ‘foothill’.[3] In Pennsylvania, the Piedmont province extends from the outskirts of Philadelphia all the way to Middletown, stopping just short of Hershey.

The Atlantic Coastal Plain province is a low-lying region between the Piedmont and the Atlantic Ocean. It is composed primarily of sedimentary rocks and loose sediment, left there from erosion of the once-mighty Appalachian Mountains and the cyclic rising and falling of sea levels.[5] During the Late Cretaceous Period (100–66 million years ago), sea levels rose hundreds of feet, covering the Coastal Plain and depositing marine sediments. The result of this marine erosion and deposition is a low-lying region that is remarkably flat, sloping eastward towards the ocean at an average angle of less than 1°.[4]

The dramatically different geology of these two regions (rocky plateau vs sandy plains) results in a boundary known as the Atlantic Fall Line. The Fall Line is an escarpment (a cliff or steep hill, see Figure 3) that extends 900 miles from New Jersey to Alabama, and it has a considerable impact on the rivers that traverse this region on their way to the ocean.[5]

Part 2: Rivers

Many towns are established on the banks of rivers, as they provide a source of fresh water and easy navigation. When available, settlements also benefitted from proximity to waterfalls, providing a source of easily harnessed hydropower, no doubt a boon to burgeoning milling and textile industries.[6] Dozens of rivers flow from the Piedmont to Coastal Plains, including the Schuylkill, Susquehanna, Potomac, and Savannah, to name a few. In all cases, the sharp drop across the Atlantic Fall Line causes turbulence, resulting in waterfalls or rapids developing in a predictable location. The consistent topography of the Fall Line, and resulting whitewater in the rivers that cross it, proved an obstacle to navigation by boat.

Part 3: Human Nature

It turns out that rowing a boat upstream in whitewater is hard, so white settlers traveling upstream on the mighty east coast rivers often stopped when they could go no further by boat (the ‘head of navigation’). In fact, Augusta GA was explicitly founded in this manner. In 1736, James Oglethorpe ordered troops to travel upstream on the Savannah River, and to build a settlement when they could travel no further.[7] This pattern of founding cities at the head of navigation has resulted in cities being situated where nearly every major river on the east coast crosses the Atlantic Fall Line.

These include:[6]

- Trenton, NJ, on the Delaware River

- Philadelphia, PA, on the Schuylkill River

- Havre de Grace, MD, on the Susquehanna River

- Baltimore, MD, on Herring Run, Jones Falls, and Gwynns Falls

- Washington, D.C., on the Potomac River

- Richmond, VA, on the James River

- Augusta, GA, on the Savannah River

- Tuscaloosa, Alabama, on the Black Warrior River

Though we may not always be able to see it, geology has a direct effect on our everyday lives. The boundary between two dissimilar types of rock created topography that generates river rapids. This may have been a non-issue, had the preferred method of travel been different, but these rapids proved an obstacle to boats exploring inland from the coast. These common factors resulted in a similar pattern of settlement along the Atlantic coast, spanning an area over 900 miles long.

TL:DR

- There’s a geologic boundary called the Atlantic Fall Line that extends from NJ to AL, and causes rapids in rivers.

- White explorers, traveling upstream by boat, stopped at the rapids and settled down.

- Ancient rocks have a greater influence on our modern world than we often realize.

References

1. Fenneman N. M. (1917). Physiographic Subdivision of the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 3(1), 17–22. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.3.1.17

2. A Tapestry of Time and Terrain, USGS, https://pubs.usgs.gov/imap/i2720/.

3. “piedmont”. Dictionary.com. 2023. https://www.dictionary.com/browse/piedmont

4. Maryland Geology, Maryland Department of Natural Resources, http://www.mgs.md.gov/geology/

5. The Atlantic Coastal Plain, Department of Geography and Environmental Science, City University of New York, http://www.geo.hunter.cuny.edu/bight/coastal.html

6. Freitag, Bob; Susan Bolton; Frank Westerlund; Julie Clark (2009). Floodplain Management: A New Approach for a New Era. Island Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-59726-635-2.

7. Robertson Jr., Thomas Heard (2002). “The Colonial Plan of Augusta”. Georgia Historical Quarterly. 86 (4): 511.