By Seth Kabonick

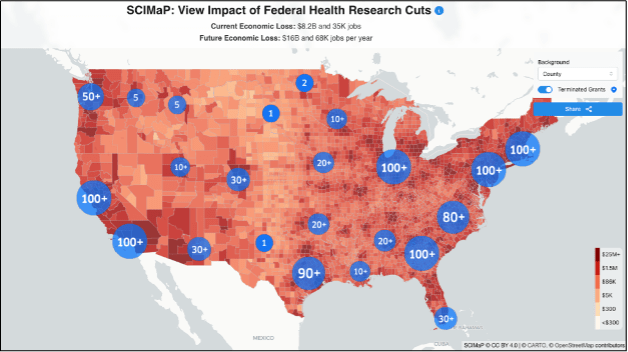

Ernest Hemingway describes the rising of the morning sun as something that happens slowly at first, then all at once. This quote has been used to illustrate everything from financial markets to drunkenness, but I believe it also applies to recent challenges plaguing the scientific community. It has been a long and bumpy few months for science as we have reached the end of the new administration’s first year. Institutional cuts in research funding, which are necessary to pay students and employees or cover operating costs, are becoming more frequent1 (Figure 1), distinguished professors are having funding revoked over political disagreements involving their universities2, and our acting director of health continues to doubt vaccine efficacy, a position which – while lacking in scientific merit – has proven a personally profitable facade. While I typically enjoy writing about cool science, both casually and professionally3, I feel compelled to offer a sobering outlook on the public perception of our work and why it matters so much that we advocate for common sense research that is performed rigorously and founded on solid findings.

Today, the broader academic community is suffering acute effects caused by the distrust in science because of sweeping policy changes that have largely affected basic research efforts rather than translational medicine. But if the political and social pressure against academics continues to increase, we will almost certainly see a catastrophic increase in research funding cuts and misguided research regulations that culminate in worsened patient care and a sharp reduction of innovative treatments. At that point, we will have fallen off the metaphorical cliff.

I hope this piece provides insight into what is currently happening to the public’s opinion, government funding, and the scientific job market. I will also provide some avenues to help invoke change to all the above.

The turmoil surrounding established science

I grew up deep in the hills of central Pennsylvania, so I am no stranger to scientific distrust. It is striking how many people believe that vaccines – and apparently, now Tylenol – cause autism (despite this being a long-debunked notion4,5), that evolution is a hoax, and that the earth is flat. According to a 2021 POLES survey, 19% of all Americans doubt the earth is a globe6. Pause a minute and let that really simmer.

Potentially most alarming is the disinformation surrounding scientific studies and their safety, efficacy, and validation. Multiple projects, such as mRNA vaccines for cancer or HIV/AIDS treatments, have been caught in bipartisan crossfire during the transition between administrations. This means that treatments which dramatically improve patient outcomes could be deprioritized or entirely removed. Such is the case for mRNA vaccines, where funding was universally pulled, totaling more than $500 million in cuts7. In my experience, large public budget cuts frequently sway public opinion about ongoing research and seed distrust about productivity. This, coupled with drastic employee cuts across the NSF and NIH have created a perfect storm that has derailed many near-future therapeutics.

Other examples of turmoil include factually incorrect public statements by elected officials on the way scientific studies are performed and the validity of their findings. In a recent interview, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., goes directly against the ethos of medical research and practicing clinicians:

“Every level, from the doctors, to the hospitals, to the insurance companies, the pharmaceutical companies, people make money by keeping Americans sicker.”

I want to be clear: the administration has every right to change the priorities for allocation of NIH funding, and this commonly happens as leadership turns over every few years. However, many of the arguments put forward to justify these current changes are not about what type of research to prioritize, but whether research should be prioritized at all.

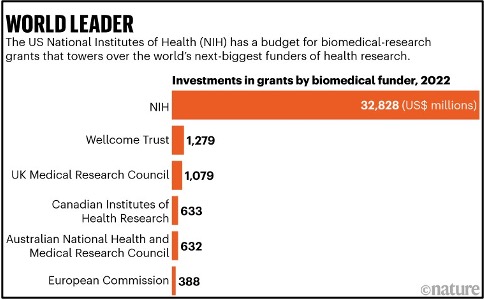

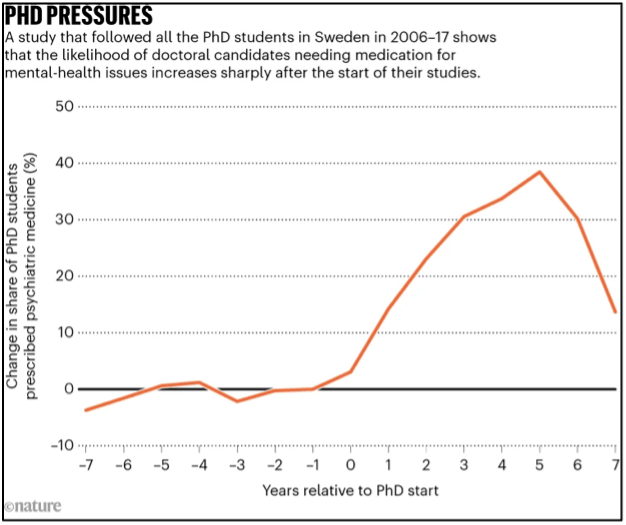

Importantly, it seems that rather than coordinating the next generation of basic and translational research, the administration has put itself at odds with many agencies that established the United States as a juggernaut of research (Figure 2). It is difficult to predict what outcomes these decisions will yield in the next few decades, but it is undeniable these cuts have already left the scientific community feeling tired and wary about the future of the system in which they have invested so much time and energy, with many PhD students needing to seek out professional help (Figure 3).

While it often feels that there is little that can be done by academic researchers with regard to federal management of research funds, it is clear that academics are not doing enough to communicate their science effectively to the general public, and this further erodes the crumbling trust between scientific and lay communities.

No matter how baseless the attacks against our work’s credibility seem, the responsibility to defend against false claims about research integrity and findings will always fall on our shoulders. In the age of misinformation, we would do well to open dialogue that stems from a place of understanding rather than condescending authority; this kind of earnest engagement and conversation will be the first and greatest step in (re)gaining trust. In many ways, graduate students at Penn State College of Medicine are actively doing this by writing for Lions Talk Science, participating in local science fairs, and presenting at nearby undergraduate institutions. Outside of the academic circle of Penn State, organizations, such as Stand Up for Science, can also provide an outlet for our time and resources to counter the negative repercussions of scientific misinformation.

The agencies that fund basic and translational research have begun to turn on many projects for a variety of reasons. In some cases, funding has been reduced or even directly terminated for the mention of terms in grants that could be interpreted as diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives. A good example of this is the complete termination of F31-Diversity applications (the primary graduate student funding opportunity from the NIH) this past April, which indiscriminately set many students back several months following the submission of the more than 50-page application package. This termination action was especially surprising given that F31-Diversity applications do not differ significantly from the standard F31 format. Despite this, submissions were outright rejected rather than considered with the other study sections, which I interpret as a direct attack on minority communities and the future of academic science.

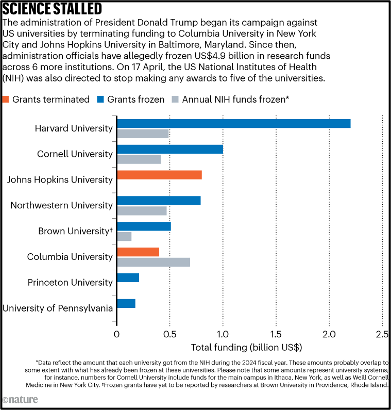

Previously untouchable universities, like Harvard and Columbia, have engaged in major bouts of funding disputes with the administration over DEI studies and policies (Figure 4). This struck fear into Penn State and other public universities, which are not strongly supported by private donors and therefore far less capable of weathering sudden changes in funding. For example, roughly 60% of all NIH funding acquired by investigators at Penn State are allocated as operating costs that help keep the lights on in the research institutions, which was temporarily cut to 15% nationally, resulting in a predicted 41.4 million dollar loss. If government funding were to be pulled, it would affect much more than basic research. It would be crippling for the development of novel therapies to save lives.

Restricting funding at the individual and institutional level has injected an unhealthy dose of unpredictability into the lives of scientists that ultimately slows productivity. This, paired with the innumerable responsibilities of a principal investigator (lab leader) and increasingly competitive funding paylines, has contributed to a record level of early career burnout, and record numbers of researchers finding positions abroad8.

The public and private job market sectors are recruiting fewer employees

The unpredictability of government funding decisions incites fear in both the academic and private job market sectors. Historically, chaos forces institutions and companies to be more conservative in hiring candidates that are promising but have little work experience, and more proactive in cutting corners on more risk-adverse research. Job market surveys confirm this, with many organizations initiating hiring freezes and consolidating employee numbers9. This floods the job market with candidates that have 1-5 years of experience, which consequently stifles the recruitment of those directly out of undergraduate or graduate school. Similarly, in the academic sector, dramatic cuts to funding have also left many labs hesitant to add new post-doctoral students or technicians10. These challenges have left many unanswered questions surrounding career paths for graduate and post-doctoral students, myself included.

So, what’s the silver lining?

Honestly, in the short-term, I don’t know, maybe yoga with guided mediation for peace? With several more years left of the current political administration, and few signs of a dramatic change in course, things will likely get much worse before the scientific community sees any improvement.

However, as I sought out sources for this piece, one positive aspect continually revealed itself: the passion and persistence of the scientific community. As scientists, we experience daily failures as a part of research, which fosters a resilience that also extends into our character. Moreover, the scientific community has universally condemned these changes while supporting its members through writing, discussions, and even funding in some cases. I was compelled to write this article to encourage a similar rallying of the community at the Penn State College of Medicine. The only way we really improve the situation surrounding science and the public is to empathetically engage in dialogue with non-scientists so we can bridge the gap in understanding and better learn how to ensure that our research has the greatest and most useful real-world community impact. I am excited to learn what challenges come up next, how they affect Penn State, and how our community adapts.

TL; DR

- There is much turmoil surrounding academic and industrial sciences

- Government funding for needed research continues to decline

- The job market for academics is becoming increasingly more challenging

- It is imperative to engage with non-scientists about the effects of these cuts

Reference

- Garisto, D. & Kozlov, M. US Supreme Court allows NIH to cut $2 billion in research grants. Nature 645, 18–19 (2025).

- Brave, H. of the. I’m an award-winning mathematician. Trump just cut my funding. https://newsletter.ofthebrave.org/p/im-an-award-winning-mathematician (2025).

- Kabonick, S. et al. Hierarchical glycolytic pathways control the carbohydrate utilization regulator in human gut Bacteroides. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41467-025-59704-3 (2025) doi:10.1038/S41467-025-59704-3.

- Eggertson, L. Lancet retracts 12-year-old article linking autism to MMR vaccines. CMAJ Can. Med. Assoc. J. 182, E199–E200 (2010).

- Andersson, N. W., Bech Svalgaard, I., Hoffmann, S. S. & Hviid, A. Aluminum-Adsorbed Vaccines and Chronic Diseases in Childhood. Ann. Intern. Med. 178, 1369–1377 (2025).

- Conspiracy vs. Science: A Survey of U.S. Public Beliefs. Carsey School of Public Policy https://carsey.unh.edu/publication/conspiracy-vs-science-survey-us-public-beliefs (2022).

- US government slams mRNA vaccine research. Nat. Biotechnol. 43, 1400–1400 (2025).

- Witze, A. 75% of US scientists who answered Nature poll consider leaving. Nature 640, 298–299 (2025).

- Masson, G. & Incorvaia, D. Fierce Biotech Layoff Tracker 2025. https://www.fiercebiotech.com/biotech/fierce-biotech-layoff-tracker-2025 (2025).

- Uncertain times. Nat. Mater. 24, 805–805 (2025).