By Arrienne Butic

In 2001, avid snake collector Tim Friede embarked on a mission that was equal parts bold and dangerous – in a bid to obtain immunological protection from his venomous reptilian charges, he began dosing himself with snake venom.

Over a 17-year period, Friede injected himself with venom more than 850 times and was bitten by snakes more than 200 times. Friede’s unusual self-experimentation drew the attention of Jacob Glanville, an entrepreneur and immunologist interested in developing a multitude of immunotherapies, from broad-spectrum vaccines to COVID-19 therapeutics. At the time, Glanville was interested in developing a snake antivenom from human antibodies.

“I remember calling [Friede] and being like, ‘Look, I know this is awkward, but I would love to get my hands on a little bit of your blood,’” Glanville said in a statement to Science. In a quote to The Guardian, he notes, “I contacted him because I thought if anyone in the world has these properly neutralizing antibodies, it’s him.” With Friede’s blood, Glanville sought to develop something that has eluded toxinologists for ages: a universal snake antivenom.

Snakebite envenomation: the problem, the treatment, and the problems with the treatment

Envenomation refers toexposure to venom typically through a bite or sting from a venomous animal. The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies snakebite envenomation as a neglected tropical disease because the majority of global cases occur in low- and middle-income in the tropics1. According to the WHO, 4.5 to 5.4 million people are bitten by snakes annually, with 1.8 to 2.7 million developing clinical illness and 81,000 to 138,000 dying from fatal complications.

The only current treatment for snakebite envenomation is snake antivenom, which is produced by immunizing an animal host with low doses of venom. Introduction of small amounts of venom into the bloodstream prompts the immune response to generate venom-specific antibodies. These antibodies are specialized proteins generated by the immune system that can recognize and neutralize, or render ineffective, toxins found in snake antivenom2.

Antibodies act on toxins either directly or indirectly. During direct inhibition, antibodies directly bind to the toxin, preventing it from interacting with its intended target by competing for the interaction site. Antibodies can indirectly inhibit venom toxins in multiple ways. One way is through allosteric inhibition, which occurs when an antibody binds to a toxin and causes the toxin molecules to change shape. Shape is paramount for biological interactions. Like how a key needs to fit its lock, two biological entities – such as an antibody and its recognized target, or a toxin and its receptor – need to fit together properly to trigger downstream effects. By altering the shape of the toxin, antibodies can keep the toxin from binding to its receptor, ultimately preventing the toxin from causing harm. Moreover, some toxins are composed of multiple components; an antibody can also indirectly inhibit toxins by interfering with the coming-together of these components, thereby preventing the formation of complete toxins.3

Although antibodies produced from snake venom are useful, they exhibit shortcomings that limit their effectiveness as treatments. On the one hand, antivenom is highly effective when utilized against the matching target; on the other, antivenoms are only specific to a single species or a small group of related species2. Due to the diversity and complexity of snakes and their venom composition, no universal antivenom exists4. Thus, proper identification of the offending snake is required for choosing the right antivenom, something that is not always possible.

Glanville, who grew up in Guatemala, spoke on this subject with The Guardian. After one is bitten by a snake, it is recommended that “you try to catch the snake and bring it in in a plastic bag so they can determine if they have an appropriate antivenom,” he says. “It’s not a great option to go chasing after the snake that’s just bitten you.” Additionally, although development of antivenom has significantly improved since its genesis, adverse reactions, such as anaphylaxis, can still occur due to the antivenom’s non-human origins5. A universal snake antivenom developed from human antibodies would bypass these issues, making it an incredibly valuable goal in antivenom development.

A three-part antivenom cocktail targeting three snake toxins

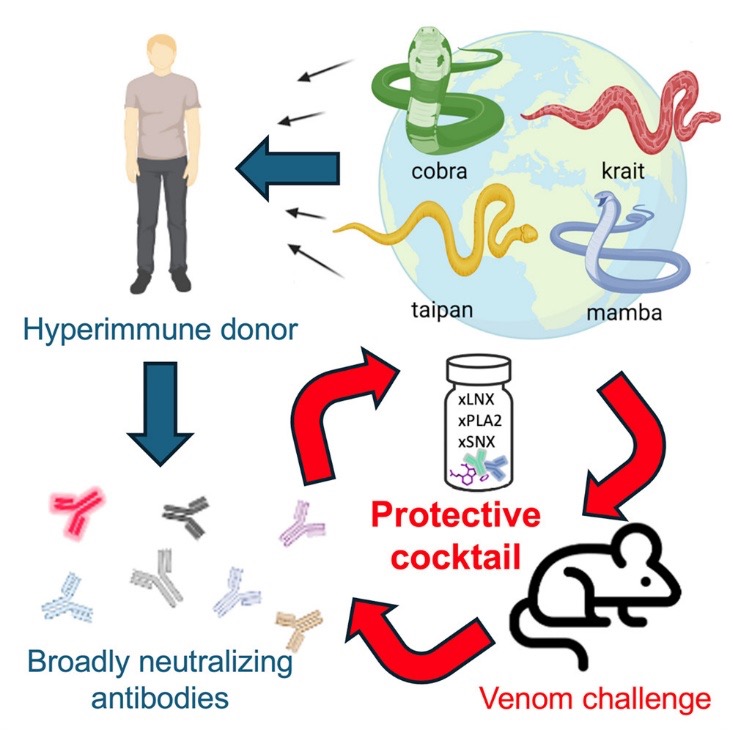

By the time Glanville reached out to Friede, Friede had dosed himself with venom from mambas, cobras, rattlesnakes, water cobras, and taipans, a few krait species (common and banded), the Eastern coral snake, the tiger snake, and the Eastern brown snake. In a study published in Cell earlier this year6, Glanville and colleagues isolated neutralizing antibodies that targeted particular snake venom toxins from Friede’s plasma and assessed the antibodies’ effectivity in vivo – specifically, in mice (Figure 1).

The authors focused on venom toxins from the Elapidae family, which encompasses almost half of existing venomous snake species7. Elapidae venom is primarily composed of three-finger neurotoxins (3FTXs), a family of toxins that binds multiple types of ion channels. Ions are charged molecules, and molecular channels for many – like sodium and potassium – are essential for keeping cells alive. Unsurprisingly, venom blocking these passageways can lead to major health crises8.

3FTXs also bind other cell surface receptors, such as receptors for acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter important for neuromuscular signaling – thus leading to muscle paralysis. As 3FXTs are a diverse group of toxins, they are associated with a wide range of effects, from seizures and cardiac arrests to alterations in blood pressure, coagulation, and cell adhesion7. The broad umbrella of 3FXTs includes two sub-groups of toxins: long-chain neurotoxins (LNXs) and short-chain neurotoxins (SNXs)2. As if that weren’t enough molecular weaponry to wreak havoc on a snake-bitten victim, Elapidae venom also includes phospholipase A2s (PLA2s), which disrupt the integrity of cell membranes, particularly those of muscle cells, and can thus induce muscle damage, as well as a variety of other serious health issues.9

Glanville and colleagues initially identified one LNX-specific antibody from Friede’s blood, which they named LNX-D09. After demonstrating that LNX-D09 selectively bound a panel of LNX homologs (other molecules shaped like LNX toxins), researchers assessed whether LNX-D09 could protect mice from snake venom made up of 3FTXs (remember, that’s the larger umbrella group that LNX toxins fall under). With LNX-D09 administration, mice were protected from three cobra species, the black mamba, and the king cobra.

To combat the PLA2s in Elapidae venom, researchers combined varespladib, a broad-spectrum PLA2 inhibitor, with LNX-D0910. Both LNX-D09 and varespladib worked together to provide protection from three additional species, drastically increasing the efficacy of antivenom as a treatment for snake bites.

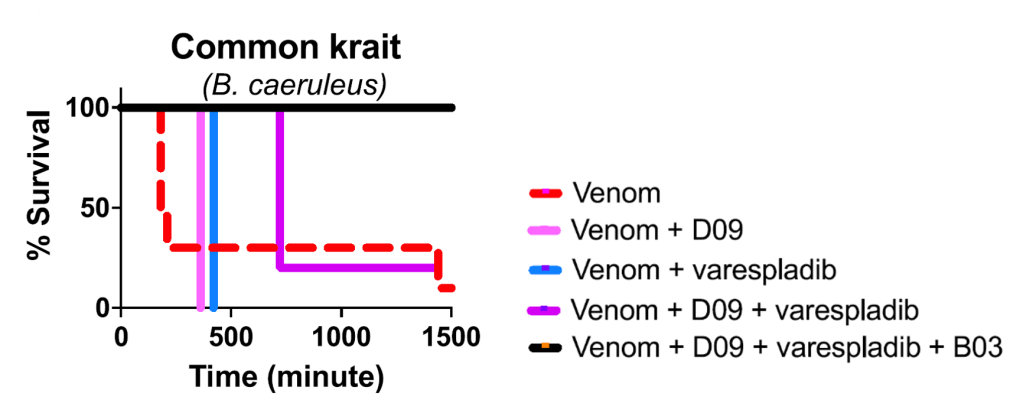

Friede’s plasma also yielded a second neutralizing antibody that targeted SNXs, which they called SNX-B03. After some preliminary investigation of the antibody, Glanville and colleagues added SNX-B03 to the LNX-D09 and varespladib mixture. They hypothesized that the resulting cocktail, which targets three common venom toxins, should be effective against a wide range of Elapidae species. The cocktail was tested in vivo by injecting mice with a venom-cocktail mixture in controlled doses. Although common krait venom, which is composed of 64.5% PLA2 and 19% 3FTX, typically induces death in mice as early as 3 hours, adding either LNXD09 or varespladib increased survival time to 6 and 7 hours. Utilizing the three-part cocktail (containing SNX-B03, LNX-D09, and varespladib) fully protected (in other words: they lived!) the mice from common krait venom (Figure 2).

Ultimately, the three-part cocktail was tested in mice against a panel of 19 Elapidae snakes, species that the WHO has listed as medically concerning6. The cocktail provided full protection against ten WHO Category 1 snakes, which are defined as medically significant species that are widespread, extremely venomous, and cause several snakebites, resulting in morbidity, disability, or mortality. The cocktail also afforded protection for three WHO Category 2 snakes – highly venomous snakes also capable of causing high morbidity, but which are less frequently observed (due to behavior or habitat) or for which less epidemiological data is available. Partial protection was observed for five WHO Category 1 snakes and one WHO Category 2 snake6. The authors concluded that the three-part cocktail provided in vivo protection against a variety of Elapidae species, thus offering as-yet unparalleled broad-spectrum protection and marking a major breakthrough in the development of a universal antivenom.

Caveats and future directions

Although this is undoubtedly an exciting new direction in the field of toxinology, all in vivo results were conducted in mice and are thus still preliminary. As the authors themselves pointed out, the cocktail needs to be tested in larger model organisms6. Furthermore, the study’s experimental setup for examining effect on survival, which involved administering the venom along with the antibody cocktail at the same time, is not representative of the dynamics of a real-life snakebite envenomation rescue. Nicholas Casewell, a toxinologist at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, observes that experiments in which there is a delay between venom administration and cocktail injection may “more closely mimic the situation in humans.”

Moreover, the study focused on Elapidae species, which only comprises around half of venomous snake species. The Viperidae family constitutes the other half, with a handful of venomous snake species in the Atractaspididae, Colubridae, and Hydrophidae families11. Creating more broadly specific antibodies to neutralize venom from these families of snakes would be valuable and necessary in formulating a true universal antivenom.

Additionally, if the three-part cocktail successfully makes it through clinical trials, the cost of production and accessibility may be a significant barrier to treatment. As a Neglected Tropical Disease, snakebite envenomation typically affects individuals in countries with underdeveloped health infrastructure and unregulated pricing structures, meaning poor geographic access to antivenom and prohibitively expensive prices12. A universal antivenom will ideally be effective, economically feasible to produce on a large scale, and accessible to those who need it.

Moving forward, Glanville plans to collaborate with veterinarians in Australia for opportunities to assess the cocktail’s effectiveness in dogs bitten by venomous snakes. Meanwhile, Friede, who now serves as the Director of Herpetology at Glanville’s biotech company, Centivax, no longer self-immunizes with snake venom. As he tells The New York Times, “I’m really proud that I can do something in life for humanity, to make a difference for people that are 8,000 miles away, that I’m never going to meet […].” This unexpected partnership between a reptile enthusiast and an immunologist yielded work that marks a promising step towards a world in which a venomous snakebite could be an easily treatable – if painful – plot twist in a person’s life story, rather than marking the end of one.

TL; DR:

- To advance science, a man injected himself with different snake venoms over 17 years

- Scientists isolated and identified two venom-specific antibodies from that man’s blood

- Researchers combined these antibodies with varespladib, a known inhibitor of a specific snake venom toxin

- The resulting three-part cocktail was tested in mice and found to protect against venom from a range of different snake species

Reference

- Chippaux, J.-P. Snakebite envenomation turns again into a neglected tropical disease! J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis 23, 38 (2017).

- Silva, A., Cristofori-Armstrong, B., Rash, L. D., Hodgson, W. C. & Isbister, G. K. Defining the role of post-synaptic α-neurotoxins in paralysis due to snake envenoming in humans. Cell Mol Life Sci 75, 4465–4478 (2018).

- Dias da Silva, W. et al. Antibodies as Snakebite Antivenoms: Past and Future. Toxins (Basel) 14, 606 (2022).

- Jiang, Y. et al. Venom gland transcriptomes of two elapid snakes (Bungarus multicinctus and Naja atra) and evolution of toxin genes. BMC Genomics 12, 1 (2011).

- León, G. et al. Pathogenic mechanisms underlying adverse reactions induced by intravenous administration of snake antivenoms. Toxicon 76, 63–76 (2013).

- Glanville, J. et al. Snake venom protection by a cocktail of varespladib and broadly neutralizing human antibodies. Cell 188, 3117-3134.e11 (2025).

- Kelly, C. M. R., Barker, N. P., Villet, M. H. & Broadley, D. G. Phylogeny, biogeography and classification of the snake superfamily Elapoidea: a rapid radiation in the late Eocene. Cladistics 25, 38–63 (2009).

- Hiremath, K. et al. Three finger toxins of elapids: structure, function, clinical applications and its inhibitors. Mol Divers 28, 3409–3426 (2024).

- Xiao, H., Pan, H., Liao, K., Yang, M. & Huang, C. Snake Venom PLA2, a Promising Target for Broad-Spectrum Antivenom Drug Development. Biomed Res Int 2017, 6592820 (2017).

- Xie, C. et al. Varespladib Inhibits the Phospholipase A2 and Coagulopathic Activities of Venom Components from Hemotoxic Snakes. Biomedicines 8, 165 (2020).

- Tednes, M. & Slesinger, T. L. Evaluation and Treatment of Snake Envenomations. in StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL), 2025).

- Potet, J. et al. Access to antivenoms in the developing world: A multidisciplinary analysis. Toxicon X 12, 100086 (2021).