By Katie Kimbark

“Any man could, if he were so inclined, be the sculptor of his own brain.” – Santiago Ramón y Cajal

Brain injuries are diverse and complex, ranging from strokes to traumatic brain injuries (TBIs), and impact millions of individuals globally each year. Over the past several decades, scientific consensus on brain injuries, specifically regarding recovery, has shifted dramatically. Many organs, like skin, have the capacity to renew their component cells, which explains why superficial wounds can heal relatively quickly. In contrast, the brain was long considered to be a “nonrenewable organ” because it was thought to lack stem cells – unspecialized cells capable of differentiating into the diverse cell types needed for tissue maintenance and repair.1,2 However, the last 50 years of research have revealed that the brain is much more adaptable than previously believed.

We now know that the brain possesses the ability to reorganize existing circuits to compensate for lost or damaged connections.2 If there’s one takeaway you have from this article, I hope it’s that brain injury recovery is far more dynamic than we used to think and that recent findings are providing newfound hope for patients.

The evolution of perspectives on neural repair

Prior to the 1960s, the “no new neurons” dogma was widely accepted. This theory suggested that the brain contained a finite number of neurons and fixed neural circuits. Simply put, this means that scientists believed that the brain possessed negligible capacity for regeneration. However, this dogma was clearly not absolute, as many patients with brain injuries demonstrated at least partial recovery. Their ability to gradually regain basic motor and cognitive functions indicated at least some capacity for recovery.

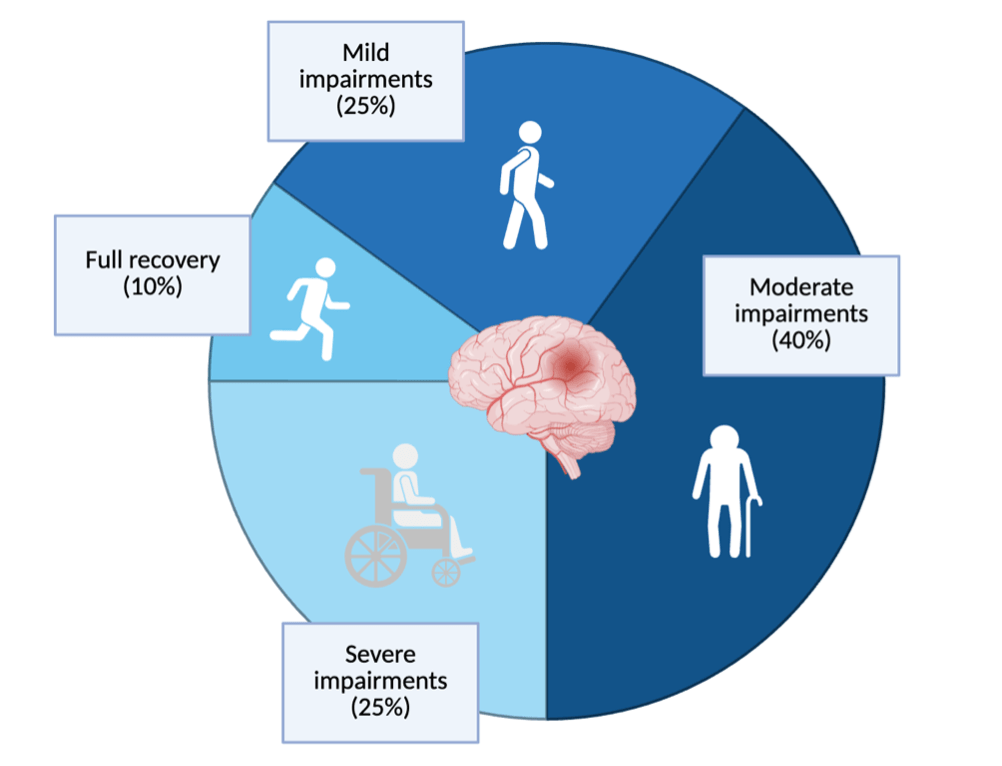

Numerous studies have since provided evidence of the production of new neurons in fully developed brains and of the brain’s ability to rewire existing circuits to regain function,2 thereby introducing the possibility for repair following injury. Still, recovery in these patients is often incomplete: few survivors achieve full restoration of function. This restriction suggests that the brain contains some inherent mechanism that limits its regenerative capacity. Accordingly, strokes and TBIs remain the leading causes of disability among adults globally due to the long-term functional deficits that come with incomplete recovery.3 Only around 10% of patients make a fully recovery (Figure 1), highlighting the need for increased understanding of the underlying physiology of brain injuries and recovery.3

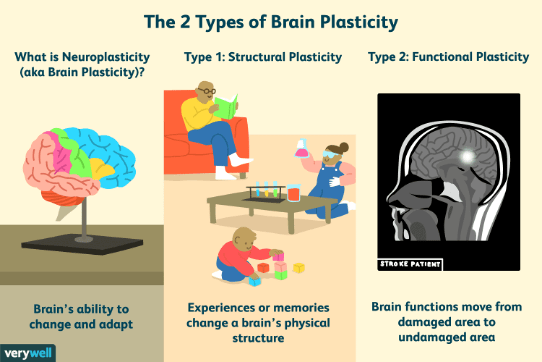

Cumulatively, the ability of the brain to adapt and reorganize is defined by the term “neuronal plasticity,” or neuroplasticity (Figure 2). Neuroplasticity can be broken into two categories: structural, when the brain rewires to make new connections (which is what happens when we learn something new or make a memory), and functional, which is when the brain modifies pre-existing circuits in an effort to restore function following damage.2 Neuroplasticity underlies the brain’s adaptive potential, and thus its ability to recover from injury. Yet, definitive mechanisms that regulate neuroplasticity – and, therefore, that regulate recovery – have, for a long time, remained largely unknown.

The emerging role of CCR5 in regulating neuronal plasticity

Substantial overlap exists between a) learning and memory processes, and b) neuroplasticity in response to injury, as both involve the formation (or reformation) of neural circuits. As such, and reflective of the often serendipitous nature of scientific discovery, Dr. Alcino Silva – a leading researcher in learning and memory at UCLA – made an unexpected finding. He uncovered that CCR5, a receptor well known for its role in immune function, is also a key regulator of neuronal plasticity.

Initially, Dr. Silva and his team identified this novel role for CCR5 via a comprehensive genetic screening for mouse strains with superior learning and memory. Through this screening, they identified that mice lacking CCR5 displayed enhanced cognitive performance.6 Upon further characterization of this mouse strain, they discovered that these mice exhibited enhanced memory across numerous tasks due to increased neuroplasticity via the building and refinement of neural circuits involved in cognition.

To further verify the relationship between CCR5 expression and memory function, they generated mice that expressed more CCR5. They found that these mice exhibit cognitive deficits and reduced neuroplasticity, further emphasizing the inverse relationship between CCR5 expression and cognitive function. However, while these findings established a clear link between CCR5 and learning and memory under normal conditions, its role in the restoration of function following injury or neurodegeneration had yet to be investigated.

With these exciting new findings, Dr. Silva partnered with Dr. S. Thomas Carmichael, the Chair of the Department of Neurology at UCLA and a practicing neurologist, for his expertise in stroke and brain injury rehabilitation. Together, they employed microscopy techniques to visualize where CCR5 is expressed in the brain before and following a stroke. Interestingly, they discovered that CCR5 expression is normally very minimal, but that following a stroke, CCR5 is found in large amounts in the neurons directly surrounding the injured area, which is sustained for weeks following the initial injury.7

Using advanced genetic techniques, they were able to reduce the expression of CCR5 in the pre-motor cortex of the brains of these mice. Their results showed that inhibition of CCR5 in that brain region improved motor function recovery following stroke, and that these improvements were dependent on neuronal plasticity.7 Simply put, existing neurons extend new axons (which are the protruding components of neurons that facilitate their communication with other neurons) to rebuild damaged circuits and restore function. To further emphasize the clinical relevance of their findings, Drs. Silva and Carmichael identified a mutation in humans that encodes a dysfunctional version of CCR5. They investigated whether having this mutation led to better functional recovery in stroke patients. Their inquiry revealed that patients with this mutation, and thus impaired CCR5 function, displayed improved recovery compared to those without the mutation,7 which emphasizes the potential for targeting CCR5 as a novel therapeutic for brain injuries.

Repurposing an HIV drug for brain injury recovery

Fortunately for Drs. Silva and Carmichael, a therapy targeting CCR5, called maraviroc, was already on the market for the treatment of HIV. HIV binds to CCR5 to infect cells, and maraviroc binds to CCR5 to block this receptor’s activity. Maraviroc has some capacity to cross the blood-brain barrier (the barrier that controls what can enter the brain from the bloodstream), suggesting that it could be effective in the brain. In keeping with this, clinical studies have published that treatment with maraviroc improves neurocognitive function in HIV patients8 – further emphasizing its potential as a therapy for neurological disorders.

To investigate this potential, Drs. Silva and Carmichael treated mice with maraviroc immediately following induction of a stroke. They saw that the animals treated with maraviroc exhibited improved motor recovery accompanied by increased survival of neurons and a rebuilding of broken circuits, suggesting that pharmacological interventions with drugs targeting CCR5 show promise in brain injury recovery.7 A phase II clinical trial is currently underway to investigate the effectiveness of maraviroc in stroke patients in improving extremity motor recovery,9 the results of which will offer critical insight into future therapeutic strategies for brain injury recovery.

I do want to note that, although these collective findings are very exciting, there are clear caveats to the use of maraviroc for treatment of brain injuries. As evidence of this, the results of Drs. Silva and Carmichael’s study suggested that genetic manipulation of CCR5 expression proved more effective as a treatment for brain injuries compared to the maraviroc treatment. Maraviroc’s effects, although significant, were not exceedingly biologically relevant (in other words, there is substantial room for improvement in terms of efficacy).7 This may be partially due to limitations in maraviroc’s ability to enter the brain, which would in turn inhibit its neurological effects. Accordingly, other novel compounds targeting CCR5 that cross the blood-brain barrier more readily are in development and show great promise. 10 As these therapies move closer to clinical reality, they offer a powerful reminder that a more complete recovery from brain injuries is not only possible – it is within reach.

TL; DR

- The brain can repair and rewire itself more than once believed – a process we now know is partially controlled by the immune receptor CCR5.

- Blocking CCR5 with the HIV drug maraviroc may boost recovery after stroke or brain injury, with clinical trials now underway.

Reference

- Poliwoda S, Noor N, Downs E, et al. Stem cells: a comprehensive review of origins and emerging clinical roles in medical practice. Orthop Rev. 2022;14(3):37498. doi:10.52965/001c.37498

- Fuchs E, Flügge G. Adult Neuroplasticity: More Than 40 Years of Research. Neural Plast. 2014;2014:541870. doi:10.1155/2014/541870

- Alawieh A, Zhao J, Feng W. Factors affecting post-stroke motor recovery: Implications on neurotherapy after brain injury. Behav Brain Res. 2018;340:94-101. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2016.08.029

- Rancic NK, Mandic MN, Kocic BN, Veljkovic DR, Kocic ID, Otasevic SA. Health-Related Quality of Life in Stroke Survivors in Relation to the Type of Inpatient Rehabilitation in Serbia: A Prospective Cohort Study. Medicina (Mex). 2020;56(12):666. doi:10.3390/medicina56120666

- Lakhan S, MD, PhD, et al. How Neuroplasticity Works. Verywell Mind. Accessed November 10, 2025. https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-brain-plasticity-2794886

- Zhou M, Greenhill S, Huang S, et al. CCR5 is a suppressor for cortical plasticity and hippocampal learning and memory. eLife. 5:e20985. doi:10.7554/eLife.20985

- Joy MT, Assayag EB, Shabashov-Stone D, et al. CCR5 Is a Therapeutic Target for Recovery after Stroke and Traumatic Brain Injury. Cell. 2019;176(5):1143-1157.e13. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2019.01.044

- Gates TM, Cysique LA, Siefried KJ, Chaganti J, Moffat KJ, Brew BJ. Maraviroc-intensified combined antiretroviral therapy improves cognition in virally suppressed HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder. AIDS. 2016;30(4):591. doi:10.1097/QAD.0000000000000951

- University of Calgary. The CAMAROS Trial: The Canadian Maraviroc Randomized Controlled Trial To Augment Rehabilitation Outcomes After Stroke. clinicaltrials.gov; 2024. Accessed November 10, 2025. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04789616 10. Wu QL, Cui LY, Ma WY, et al. A novel small-molecular CCR5 antagonist promotes neural repair after stroke. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2023;44(10):1935-1947. doi:10.1038/s41401-023-01100-y