By: Zekiel Factor

Humans, like all animals, instinctively rely on the assumption that the sensations we experience such as touch and sight reproduce reality. Touching a hot stove activates temperature sensors in the skin that convey pain and trigger reflexive hand withdrawal; an object moving quickly in our peripheral vision draws our gaze to enable us to dodge quickly. Although sensation has evolved to convey critical information about our environment, the information we receive is far from infallible. A hallucination is any sensory perception generated internally without external input, such that the brain mistakenly perceives the sensation as coming from the external world.1They have a wide variety of causes, including psychosis and sensory loss.2 Hallucinations stem from the complexity of the brain-body interface, with its network of critical connections which can be easily perturbed by any number of changes in functioning.

In fact, the idea that our perception may deceive us is far more fundamental than its clinical relevance to hallucinations alone. Centuries ago, the philosopher René Descartes put his perception of reality through a series of logical hurdles to determine what beliefs could be proven true when he purposefully doubted everything he knew, even his own senses. He imagined that some “evil demon” was deliberately distorting his entire experience of the eternal world, such that he could not trust what he was perceiving. Descartes’ account of systematic doubt was one of the earliest attempts on record to analyze the disconnect between the external world and our perception of it. Such pursuits helped shape the framework of epistemology, the field that studies the foundations of knowledge itself. Thus, as we continue to confront the subjectivity of our own perceptions, it is only natural that we must conceptualize hallucinations not merely as some pathological state, but as a piece of the larger perceptual puzzle giving rise to life “as we know it.”

Mapping and mismapping brain to body

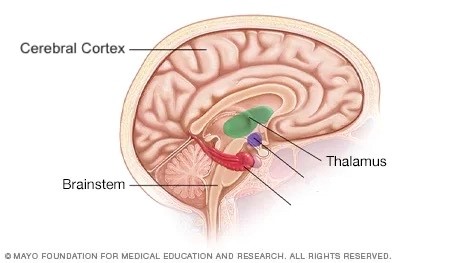

As I have discussed in a previous article, the nervous system transmits sensory signals via firing of electrical impulses through connections between areas of the brain, often termed circuits.3 Most circuits that drive sensory perception connect via the brainstem to a processing hub called the thalamus (Figure 1). The function of the thalamus is to regulate and coordinate sensations it receives from the sensory organs of the body (e.g., eyes, ears, mouth, skin).These sensations are then sent to the cerebral cortex, which is the complex outer layer of the brain (Figure 1). The cerebral cortex further processes and integrates sensations to use for higher-order cognition, such as the use of sensory perception for learning, memory, and decision making. The critical circuits between the thalamus and the cortex, also known as thalamocortical circuits, involved in sensory processing seem to be integral in the generation of hallucinations across a wide variety of underlying causes.2, 4-5

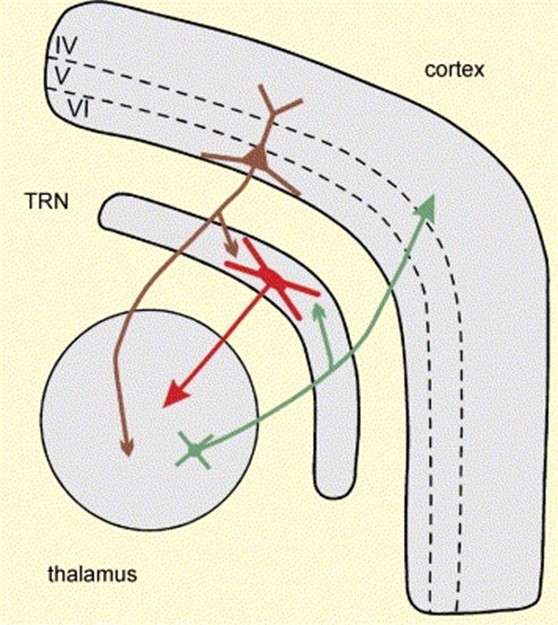

Because thalamocortical circuitry is fundamental for most sensory transmission, perturbations to this circuit may play a role in multiple different causes of hallucinations. For example, one potential shared mechanism for hallucinations could relate to the thalamic reticular nucleus (TRN), a specialized region of the thalamus. The TRN modulates communication between the rest of the thalamus and the cortex, mainly by acting like a gate that stops extraneous signals, such as those that do not come from external sensations (Figure 2). If the TRN acts like a “leaky gate” by letting extraneous signals through, this causes the internal generation of sensory cortical signals without external input, increasing vulnerability to hallucinations2, 6. Therefore, the critical role of the TRN helps to prevent the conscious perception of these spontaneous signals and facilitates selective attention to only important sensory inputs.

Sensory loss and input-output disentanglement

Although hallucinations can stem from many different causes, sensory loss leading to hallucinations is a well-documented phenomenon across multiple senses, including sight (visual release hallucinations, AKA Charles Bonnet syndrome), hearing (tinnitus and musical ear syndrome), and body sensations (phantom limb). Visual release hallucinations are characterized by vivid visual imagery perceived after vision loss. Tinnitus is an internally generated ringing in the ears following hearing loss. Musical ear syndrome is a more complex manifestation of tinnitus, resulting in entire songs being hallucinated, ranging from pop music to spiritual hymns. Phantom limb syndrome is the experience of body sensations (touch, pain, movement, and position in space) from a limb that has been lost. All these cases rely on the brain being wired by lived experience to expect input of sensation prior to losing it, showing shared neural underpinnings. In contrast, people who are born deaf, blind, or with limb differences do not experience these perceptual disturbances.8 This distinction gives us a clue about the etiology of these hallucinations: they require the brain to lose input it has already gotten used to working with.

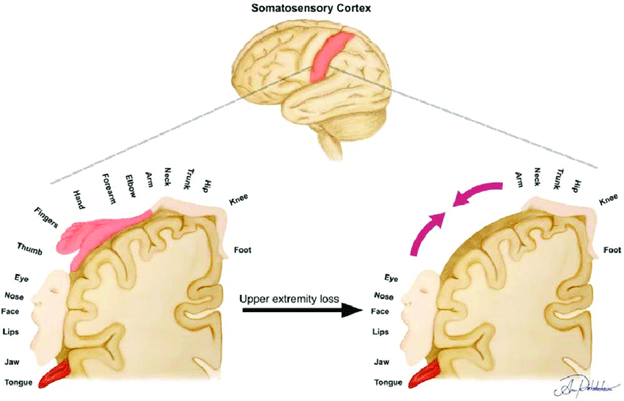

Senses are first transmitted via peripheral inputs, external signals from sensory organs (e.g., eyes, mouth, skin). Deafferentation—the loss of peripheral inputs—means that sensory networks, pathways which transmit information from the body to the brain, are no longer being regulated by inputs from sensory organs. This loss of peripheral control allows signals to be transmitted without any external trigger, tricking the brain into sensing something where there’s actually nothing. 8-10 For example, deafferentation that occurs after limb loss can cause now-unused neural networks to be integrated into usable circuits (Figure 3). More recent studies8-9 have also demonstrated that the thalamus may rewire itself in a similar way to the cortex. “Crossed wires” during reorganization, both cortical and thalamic, are theorized to contribute to phantom limb pain. However, recent evidence highlights that increased reorganization does not drive pain severity, implicating more specific patterns of rewiring that may play a role, termed maladaptive plasciticy.17-18 Abnormal processing of peripheral inputs (e.g., touch, temperature, pain, or body position in space) can also play a role, with nearby tactile sensations being mistakenly localized to where a lost limb used to be.8-10

Seeing and believing

Insight is someone’s self-awareness that they have a condition that is distorting their perception, for example causing them to hallucinate. Insight is facilitated by reality monitoring, which is the ability to accurately distinguish between internally generated experiences (hallucinations) and external reality (what is happening in the external world). The ability to accurately reality monitor differs for each person depending on the circumstances and underlying cause of hallucinations. Insight that one’s condition is causing hallucinations is generally intact in sensory loss. For example, those with musical ear syndrome can recognize the songs they hear are not externally generated because they know that they are deaf.8, 10

Conversely, insight is generally impaired during psychotic episodes. The constellation of cognitive and behavioral changes that define psychosis includes hallucinations, delusions, and disorganized thought patterns.13 Psychosis generally entails some loss of accurate reality monitoring.16 Psychosis itself has many causes, although psychiatric causes such as schizophrenia or bipolar mania are the most well-known. Because it is generally not possible to convince someone without insight that their hallucinations are not real, a cardinal rule of engaging with people experiencing psychosis is not to deny or attempt to disprove their perceptions, as it can foster mistrust. Rather, the goal is typically to reassure and support them within the context of these experiences, not explicitly endorsing hallucinations or delusions as true but also not attempting to prove them false.

Psychosis and the internal world

It is important to establish that our mechanistic understanding of psychosis is extremely incomplete. A theory centering the role of the chemical messenger dopamine, which serves many important functions including learning, motivation, and movement, is the foundation upon which antipsychotic therapies have been developed. However, the more we learn about psychosis, the more we understand that it involves complex chemical dysregulation that expands beyond only dopamine. Consequently, antipsychotics still have much room for improvement in terms of efficacy and side effect profile.12 Although far from the smoking gun it was once framed as, dopamine does play a key role in both schizophrenic and manic psychosis.13

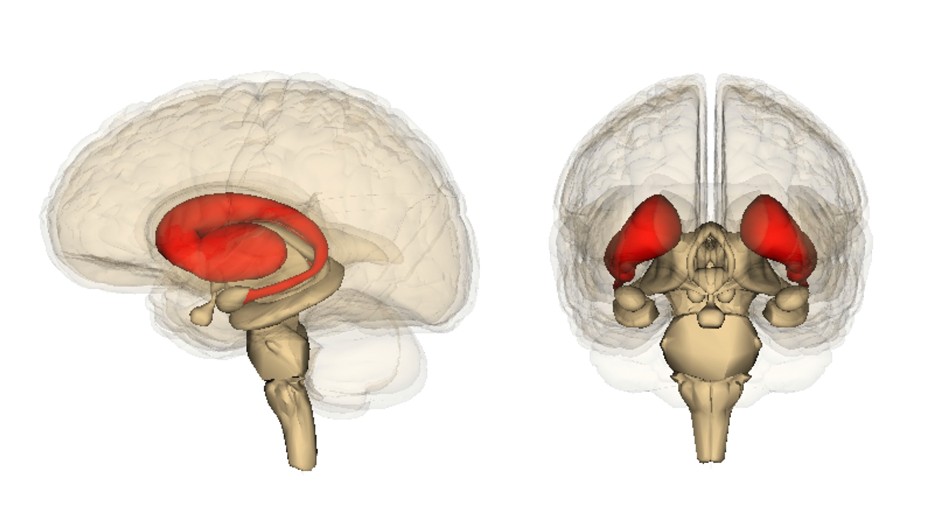

Dopamine is the main chemical in multiple circuits that help govern learning, decision making, and habit formation. These circuits release dopamine onto a deep-brain structure called the striatum (Figure 4). Signals from the striatum help us generate perceptual priors, which are expectations for how reality ought to be based on past experiences. Using priors helps us to make sense of incoming sensory inputs more efficiently. For example, we are faster at visually identifying a fork in the kitchen than in the forest. In psychotic disorders, excessive dopamine signaling in the striatum is thought to disrupt the balance between internal priors and external sensations, giving disproportionate weight to internally generated expectations—even when they are rooted in delusional thinking—relative to external sensory signals.14-15

With a common goal in mind

What we know about the neural underpinnings of hallucinations is still dwarfed by what we have yet to learn, and while commonalities and differences across etiologies offer valuable mechanistic insights, there is no singular explanatory framework. It is important that we try to understand the complex relationship between sensation and perception, not only to develop safer and more refined treatment options, but also to better understand the rich and diverse array of people’s embodied experiences. It is critical to the wellbeing of millions of people who experience hallucinations, from all walks of life and any number of reasons, that we normalize them as a common variation in human experience and bolster the strength of community-based supports. It is the nature of our senses to be easily deceived; to lead with this understanding paves the way for a more compassionate future in all perceived realities.

TL; DR

- Hallucinations have some shared neural underpinnings, but different causes, that involve different parts of the brain.

- Sensory loss makes us more likely to internally generate spontaneous sensations, while psychosis blurs our ability to distinguish between our internal and external worlds.

Reference

1. El-Mallakh, Rif S., and Kristin L. Walker. 2010. “Hallucinations, Psuedohallucinations, and Parahallucinations.” Psychiatry 73 (1): 34–42. https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.2010.73.1.34.

2. Behrendt, Ralf-Peter, and Claire Young. 2004a. “Hallucinations in Schizophrenia, Sensory Impairment, and Brain Disease: A Unifying Model.” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 27 (6): 771–87. doi:10.1017/s0140525x04000184.

3. Byrne, John H. 2024. “Introduction to Neurons and Neuronal Networks.” Neuroscience Online: An Electronic Textbook for the Neurosciences. Department of Neurobiology and Anatomy – The University of Texas Medical School at Houston. https://nba.uth.tmc.edu/neuroscience/m/s1/introduction.html.

4. Onofrj, Marco, Mirella Russo, Stefano Delli Pizzi, Danilo De Gregorio, Antonio Inserra, Gabriella Gobbi, and Stefano L. Sensi. 2023. “The Central Role of the Thalamus in Psychosis, Lessons From Neurodegenerative Diseases and Psychedelics.” Translational Psychiatry 13 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-023-02691-0.

5. Avram, Mihai, Helena Rogg, Alexandra Korda, Christina Andreou, Felix Müller, and Stefan Borgwardt. 2021. “Bridging the Gap? Altered Thalamocortical Connectivity in Psychotic and Psychedelic States.” Frontiers in Psychiatry 12 (October). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.706017.

6. Ferrarelli, F., and G. Tononi. 2010. “The Thalamic Reticular Nucleus and Schizophrenia.” Schizophrenia Bulletin 37 (2): 306–15. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbq142.

7. Pinault, D. (2004). The thalamic reticular nucleus: Structure, function and concept. Brain Research Reviews, 46(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.04.008

8. Baffour-Awuah, Kwame A., Holly Bridge, Hilary Engward, Robert C. MacKinnon, I. Betina Ip, and Jasleen K. Jolly. 2024. “The Missing Pieces: An Investigation into the Parallels between Charles Bonnet, Phantom Limb and Tinnitus Syndromes.” Therapeutic Advances in Ophthalmology 16 (January). doi:10.1177/25158414241302065.

9. Andoh, J., C. Milde, J.W. Tsao, and H. Flor. 2017. “Cortical Plasticity as a Basis of Phantom Limb Pain: Fact or Fiction?” Neuroscience 387 (November): 85–91. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.11.015.

10. Fénelon, Gilles. 2012. “Hallucinations Associated With Neurological Disorders and Sensory Loss.” In Springer eBooks, 59–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-4121-2_4.

11. Issa, Christopher J., Shelby R. Svientek, Amir Dehdashtian, Paul S. Cederna, and Stephen W. P. Kemp. 2022. “Pathophysiological and Neuroplastic Changes in Postamputation and Neuropathic Pain: Review of the Literature.” Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery Global Open 10 (9): e4549. doi:10.1097/gox.0000000000004549.

12. Spark, Daisy L., Alex Fornito, Christopher J. Langmead, and Gregory D. Stewart. 2022. “Beyond Antipsychotics: A Twenty-First Century Update for Preclinical Development of Schizophrenia Therapeutics.” Translational Psychiatry 12, no. 1. doi:10.1038/s41398-022-01904-2.

13. Jauhar, Sameer, Matthew M. Nour, Mattia Veronese, Maria Rogdaki, Ilaria Bonoldi, Matilda Azis, Federico Turkheimer, Philip McGuire, Allan H. Young, and Oliver D. Howes. 2017. “A Test of the Transdiagnostic Dopamine Hypothesis of Psychosis Using Positron Emission Tomographic Imaging in Bipolar Affective Disorder and Schizophrenia.” JAMA Psychiatry 74 (12): 1206. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2943.

14. Cassidy, Clifford M., Peter D. Balsam, Jodi J. Weinstein, Rachel J. Rosengard, Mark Slifstein, Nathaniel D. Daw, Anissa Abi-Dargham, and Guillermo Horga. 2018. “A Perceptual Inference Mechanism for Hallucinations Linked to Striatal Dopamine.” Current Biology 28 (4): 503-514.e4. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.12.059.

15. McCutcheon, Robert A., Anissa Abi-Dargham, and Oliver D. Howes. 2019. “Schizophrenia, Dopamine and the Striatum: From Biology to Symptoms.” Trends in Neurosciences 42 (3): 205–20. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2018.12.004.

16. Garrison, Jane R., Emilio Fernandez-Egea, Rashid Zaman, Mark Agius, and Jon S. Simons. 2017. “Reality Monitoring Impairment in Schizophrenia Reflects Specific Prefrontal Cortex Dysfunction.” NeuroImage Clinical 14 (January): 260–68. Doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2017.01.028.

17. Gunduz, Muhammed Enes, Camila Bonin Pinto, Faddi Ghassan Saleh Velez, Dante Duarte, Kevin Pacheco-Barrios, Fernanda Lopes, and Felipe Fregni. 2020. “Motor Cortex Reorganization in Limb Amputation: A Systematic Review of TMS Motor Mapping Studies.” Frontiers in Neuroscience 14 (April). https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2020.00314.

18. Jutzeler, C.R., A. Curt, and J.L.K. Kramer. 2015. “Relationship Between Chronic Pain and Brain Reorganization After Deafferentation: A Systematic Review of Functional MRI Findings.” NeuroImage Clinical 9 (January): 599–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2015.09.018.