By: Ceyda Yalcin

You’ve probably heard of Ozempic, or semaglutide: the celebrity-endorsed, weight-loss drug that has taken the world by storm. Originally designed to treat type 2 diabetes, these medications, scientifically known as glucagon-like-peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RA), are now being explored for their potential to treat a range of conditions from substance use disorder to neurodegenerative diseases. In the last decade, research on GLP-1 receptor agonists has skyrocketed, with a dramatic rise in published articles detailing their effects beyond glucose regulation, which include hormone production, cognitive behavior, and nervous system function1–4 . It’s not often that a single class of drugs spans such a wide range of physiologic activity, but GLP-1RAs are rewriting the playbook. So, what’s the secret? How can a drug involved in blood sugar regulation also influence behavior, addiction, and brain aging?

If you’ve already read Brianna’s great piece on GLP-1 receptor agonists as a “possible panacea” last year, you are not only familiar with GLP-1 metabolism but also know these drugs have come a long way from their diabetes-focused origins. In summary, by mimicking the gut hormone GLP-1, GLP-1 receptor agonists help balance insulin and glucagon levels, which in turn controls blood sugar levels, slows down how quickly food leaves your stomach after you eat, and reduces appetite. Brianna’s article also highlighted how GLP-1RAs have expanded into treatments for obesity, cardiovascular health and even substance use disorders by reducing drug cravings and relapse behaviors. This time, we’re zooming in and focusing on the growing evidence for the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists in treating neurodegenerative diseases, specifically Parkinson’s Disease (PD). PD is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the loss of dopamine producing neurons in a critical region of the midbrain and the accumulation of misfolded alpha-synuclein protein in the surviving neurons5. These cellular hallmarks lead to motor symptoms like tremors, stiffness, and slowed movement, as well as cognitive and emotional changes5.

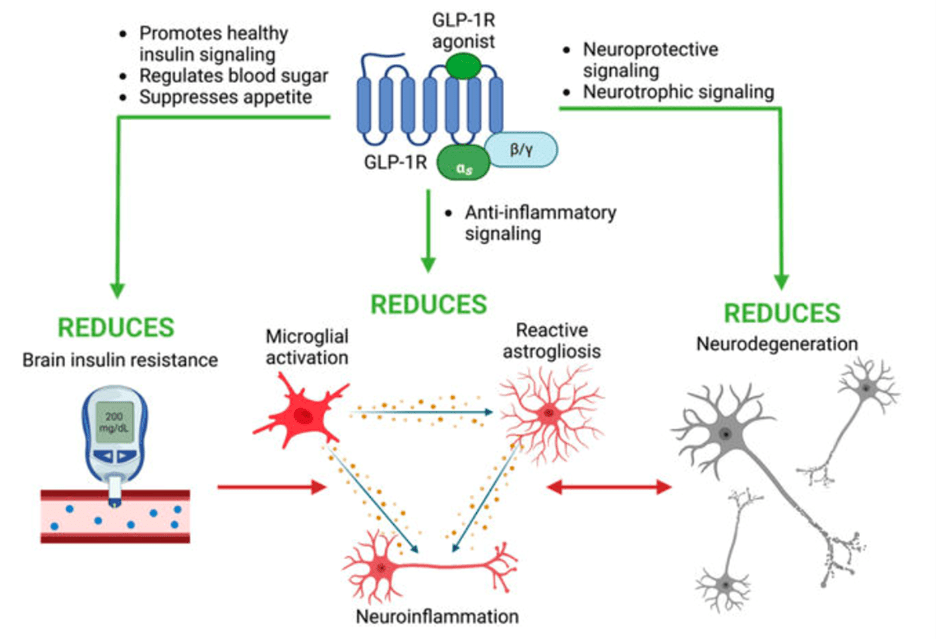

While GLP-1 receptors are well known for their role in the gut and pancreas, it turns out as neuropeptides, they are also found in brain regions involved in reward, emotion, and cognition6. Previous studies have also shown that in both non-disease and neurodegenerative disease models, GLP-1 receptor activation in neurons and glia, or the non-neuronal support cells in the nervous system, helped the brain suppress harmful inflammation, use energy more efficiently, and may even promote the growth of new cells4. These beneficial effects of GLP-1RAs are enacted through various signaling pathways inside of the cells (Figure 1) and have recently begun to be investigated for their therapeutic potential in Parkinson’s.

The brain’s immune system is known to play a major role in neurodegeneration by driving neuroinflammation. In a healthy brain, the immune response involves microglia, the brain’s immune cells that clear the nervous system of pathogens and debris, and astrocytes, cells that maintain neuronal health by providing major support to neurons and preventing neuron death. However, in response to disease in the brain such as Parkinson’s, the microglia become activated and in turn promote nearby astrocytes into assuming what is called a neurotoxic A1 state—essentially, astrocytes that kill instead of protect neurons12. Interestingly, a recent study using a mouse model demonstrated that a specific GLP-1 receptor agonist NLY01 prevents toxic A1 astrocyte formation by preventing the microglia from signaling to the neurons, which in turn stops the neurons from dying9. One important feature of NLY01 that likely accounts for its neuroprotective activity is that the drug has been modified to have a polyethylene glycol, or PEG, molecule attached to it. This PEG molecule acts like a protective coating, allowing NYL01 to stay in the body longer without breaking down. As a result, the drug has more time to travel through the bloodstream, reach the brain, and do its job. The PEG molecule also allows for the drug to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) – the layer that separates the blood from the brain tissue -more effectively to get to sites affected by the disease13. Not only does this study demonstrate the importance of glial cells in maintaining neuronal health and overall brain function, but it highlights the neuroprotective potential of GLP-1 receptor agonists. In addition to studies focused on NYL01, other GLP1-RAs are shown prevent the build-up of harmful proteins and protect against stress in PD models, which in turn translates into better motor function and less neuronal death7–11.

GLP-1RAs are also being tested in clinical trials for treating neurodegenerative diseases. In fact, as of 2020, at least eight clinical trials have investigated the therapeutic potential of various GLP-1RAs in PD, including semaglutide, which is suggested to effectively slow the progression of motor deficits in PD patients14. Follow-up trials are still ongoing to determine the efficacy of the drug in treating the cognitive deficits caused by Parkinson’s and the mechanism of action of semaglutide in PD specifically, since it remains unknown if the drug is able to cross the BBB15. Another GLP-1, exenatide, improved motor and cognitive function in PD patients for 2 months after participants stopped the medication16. In a follow-up trial these results were confirmed when exenatide-treated patients outperformed placebo for 60 weeks—with signs of sustained benefit17. More recently, other GLP-1 receptor agonists- liraglutide, lixisenatide, and NLY01- have also began clinical trials for treating PD, while exenatide has entered phases 2 and 3 of testing (See Table 1 for more) 18,19.

However, the long-term safety of GLP-1RAs in PD patients is still unknown. Many of the clinical studies showed only modest improvements, and results are difficult to interpret due to differences in PD patient groups and study designs. Stronger, longer trials are needed to determine whether these drugs offer lasting benefits and to ensure their safety across diverse patient populations. Still, early findings showing the potential of GLP-1Ras to effectively treat PD are encouraging.

One fascinating twist in this story right now is the rise of dual GLP-1/GIP receptor agonists, which combine the neuroprotective strengths of two gut hormones. Like GLP-1, GIP (glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide) also plays a role in controlling insulin and may provide additional protective effects in the brain20. By targeting both receptors at once, these new drugs might offer even greater benefits that GLP-1RAs alone. One dual agonist called DA5-CH was tested in a mouse model of PD and its effects were compared to that of GLP-1RA liraglutide11. DA5-CH outperformed liraglutide in improving motor behavior, reducing inflammation, and decreasing toxic protein levels in the midbrain. The same group also compared the performance of DA5-CH to semaglutide in a rat model of PD and found similar results10.

GLP-1 receptor agonists may have started off as metabolic medications, but as the neuroscience world pivots toward drug repurposing, GLP-1RAs are emerging as ideal candidates for neurodegenerative disease therapeutics. Repurposing existing drugs like GLP-1RAs is strategic in neurodegenerative research because they are clinically safe and already FDA-approved. This bypasses years of early safety testing, dramatically cuts development costs, and fast-tracks clinical trials for diseases that urgently need new treatments. Additionally, recent clinical trials show GLP-1’s can effectively slow down the disease progression of Parkinson’s, which is a dramatic improvement from the current treatments that focus more on symptomatic relief. With PubMed hits on “GLP-1 AND brain” doubling since 2015, it is clear the field is waking up to their potential. I sure did as a first-year master’s student!

Reference

1. Leggio, L. et al. GLP-1 receptor agonists are promising but unproven treatments for alcohol and substance use disorders. Nat. Med. 29, 2993–2995 (2023).

2. Hayes, M. R. & Schmidt, H. D. GLP-1 influences food and drug reward. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 9, 66–70 (2016).

3. Monney, M., Jornayvaz, F. R. & Gariani, K. GLP-1 receptor agonists effect on cognitive function in patients with and without type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 49, 101470 (2023).

4. Reich, N. & Hölscher, C. The neuroprotective effects of glucagon-like peptide 1 in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease: An in-depth review. Front. Neurosci. 16, 970925 (2022).

5. Poewe, W. et al. Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer 3, 17013 (2017).

6. Monney, M., Jornayvaz, F. R. & Gariani, K. GLP-1 receptor agonists effect on cognitive function in patients with and without type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 49, 101470 (2023).

7. Kopp, K. O., Glotfelty, E. J., Li, Y. & Greig, N. H. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists and neuroinflammation: Implications for neurodegenerative disease treatment. Pharmacol. Res. 186, 106550 (2022).

8. McClean, P. L., Parthsarathy, V., Faivre, E. & Hölscher, C. The diabetes drug liraglutide prevents degenerative processes in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 31, 6587–6594 (2011).

9. Yun, S. P. et al. Block of A1 astrocyte conversion by microglia is neuroprotective in models of Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Med. 24, 931–938 (2018).

10. Zhang, L. et al. DA5-CH and Semaglutide Protect against Neurodegeneration and Reduce α-Synuclein Levels in the 6-OHDA Parkinson’s Disease Rat Model. Park. Dis. 2022, 1–11 (2022).

11. Zhang, Z. et al. A Dual GLP-1/GIP Receptor Agonist Is More Effective than Liraglutide in the A53T Mouse Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Park. Dis. 2023, 1–13 (2023).

12. Liddelow, S. A. et al. Neurotoxic reactive astrocytes are induced by activated microglia. Nature 541, 481–487 (2017).

13. Dotiwala, A. K., McCausland, C. & Samra, N. S. Anatomy, Head and Neck: Blood Brain Barrier. in StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL), 2025).

14. McFarthing, K., Larson, D. & Simuni, T. Clinical Trial Highlights – GLP-1 agonists. J. Park. Dis. 10, 355–368 (2020).

15. Salameh, T. S., Rhea, E. M., Talbot, K. & Banks, W. A. Brain uptake pharmacokinetics of incretin receptor agonists showing promise as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease therapeutics. Biochem. Pharmacol. 180, 114187 (2020).

16. Aviles-Olmos, I. et al. Exenatide and the treatment of patients with Parkinson’s disease. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 2730–2736 (2013).

17. Athauda, D. et al. Exenatide once weekly versus placebo in Parkinson’s disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Lond. Engl. 390, 1664–1675 (2017).

18. Kalinderi, K., Papaliagkas, V. & Fidani, L. GLP-1 Receptor Agonists: A New Treatment in Parkinson’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 3812 (2024).

19. McGarry, A. et al. Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of NLY01 in early untreated Parkinson’s disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 23, 37–45 (2024).

20. Zhang, Z. Q. & Hölscher, C. GIP has neuroprotective effects in Alzheimer and Parkinson’s disease models. Peptides 125, 170184 (2020).