By Zoe Katz

Since the introduction of ChatGPT in 2018, the rise of generative artificial intelligence – or gen AI – has been exponential and pervasive in our society. Everywhere we look, there’s a new AI tool aimed at improving our digital experience. Be it the AI Overview on Google or Rufus on Amazon, AI is ubiquitous, ostensibly to make our experiences as users easier. As a whole, AI has the potential to be extremely useful and beneficial for our society, improving our world in a myriad of ways including by tracking air quality, measuring how certain products impact the environment, and figuring out what gaps we have in understanding current biodiversity including identifying new species1. However: all the examples just listed are instances of traditional AI, which differs greatly from gen AI.

Rather than interpreting data and identifying patterns, the purpose of gen AI is to act like a human brain – to think and create. The new era that we are entering as a society seemingly has gen AI at the center. Though gen AI is already widely used by both companies and everyday people, its negative impact on the invaluable, non-renewable resource that is our environment cannot be understated.

What is AI?

Traditional AI is used to perform a particular task based on a specific set of inputs which it was designed to understand. They are able to identify patterns from data and, from these patterns, make predictions. A fun example of traditional AI is playing a game, such as chess, against a computer. The computer knows all of the rules and possible moves that could be made, though it could not know in advance the exact order in which the human opponent will play them. It is, however, able make calculated decisions and adjust those decisions based on its opponent’s moves. Another example is when AlphaGo, a computer program, beat a master Go player in 2016 due to its ability to recognize patterns and predict better than a human is able to. Colloquially, the word “learn” can be used to describe this action of becoming better through iterative pattern recognition – however, as AI is not a conscious entity or a living being, the term “learn” is not accurate to what artificial intelligence does, and therefore, is not used in this article. Siri or Alexa are other such examples of traditional AI, but even they are slowly integrating gen AI features.

In contrast, generative AI is an evolved version of traditional AI. Unlike traditional AI, whose actions are restricted to taking in data and making predictions from those inputs, gen AI makes new data. It has the ability to create new images, videos, and art that look like a person made them – and be trained to generate and create better based on parameters that you as a user put into it. Gen AI is still a language learning model; that is, at its core, it still recognizes and predicts patterns much like traditional AI. What sets it apart is that gen AI is trained on extremely large amounts and vast types of data, giving it the appearance of creativity. In early 2025, thousands of artists wrote to an auction house in New York City urging it to cancel an upcoming auction selling AI-generated art. The reason? The gen AI model that was used to make this art was trained using the artwork from these artists without their permission.

What is the impact of generative AI on the environment?

All life on Earth is dependent on water for survival. 71% of the Earth is covered in water, but, unfortunately, most of that water is unavailable to drink. As humans, we require freshwater – it is used to cultivate our crops, water our livestock, and is a basic necessity for human life. Though freshwater only makes up 3% of the water on Earth, most of that water is inaccessible to use, as it is frozen in glaciers and polar ice caps. Humans and most other organisms require potable freshwater to live. Water from natural sources is made potable by being treated to prevent growth and ingestion of microorganisms, viruses, chemical toxins, and fecal matter, thereby making it available for human consumption.

The growing global population accordingly requires more food and water to sustain itself. Currently, water scarcity is a global problem that numerous low-income countries are facing. Living with water stress threatens peoples’ livelihoods, food and energy security, and economic development around the world. Water stress, or water scarcity, occurs when the demand for clean freshwater cannot be met by existing infrastructure. Currently, 1.1 billion people globally lack access to water. A major barrier to fixing the global water scarcity is the rapid and exponential rise in the use of gen AI.

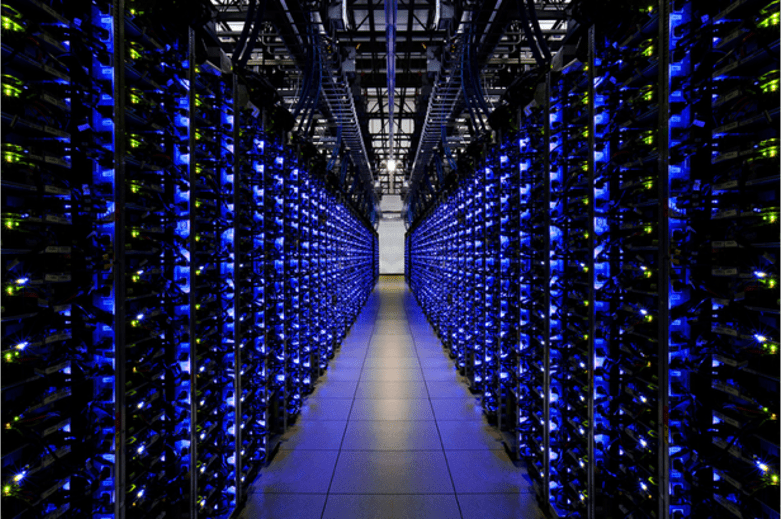

Data centers are huge temperature-controlled buildings that house hundreds of thousands of computers, computer servers, network equipment, and data storage drives (Figure 1). Their halls are filled with rows upon rows of computer servers. They are used to train and run the generative AI deep learning models (a model is an AI program that has been trained on a set of data to make predictions and decisions) that are behind ChatGPT and others. Importantly, data centers are not just used for gen AI models; they are also used for storing data in the Cloud. Downloading digital games, cloud streaming, Gmail, and Google drive use data centers.

Training and running these models and storing Cloud data requires a lot of energy – a simple query run in ChatGPT uses about 10 times more electricity than a Google internet search does! The electricity requirement is so astonishingly high because the computational power used is that much higher. All this electricity usage generates massive amounts of heat, which can be detrimental for the functionality and effectiveness of computers. Uncontrolled heat can reduce computers’ efficiency or render them inoperable, which is where freshwater comes into play.

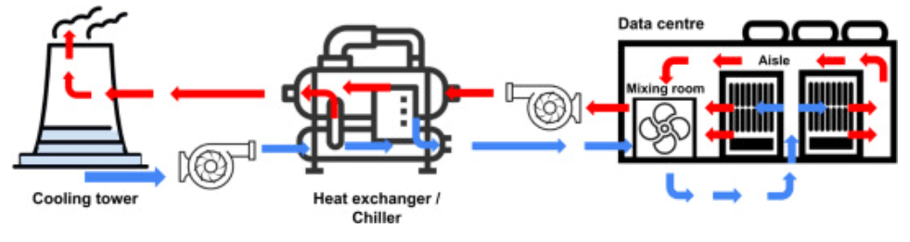

Water is used in two ways at data centers: indirectly and directly. Indirectly, water is utilized to generate the electricity needed for data centers to run, usually through hydroelectric plants. Directly, cooled water is employed to dissipate the heat generated by the data center computers. Most commonly, large-scale data centers use evaporative cooling towers to temper this heat. They work by circulating cooled water (and lowering the water temperature uses even more electricity!) through a cooling tower. Water evaporates as it cools the air being circulated, taking the heat with it (Figure 2).

When these cooling systems are used, they remove a significant amount of water from the local water cycle (the continuous movement of water from and around the Earth and throughout the atmosphere as it condenses, evaporates, and precipitates) permanently – this water is consumed through evaporation and does not return to the water cycle. This is because the water used is treated with chemicals to prevent bacterial growth and corrosion, making it unable to be consumed humans or used in agriculture. These losses are extreme. A single data center can use up to 500,000 gallons of freshwater per day. For reference, this amount of water is equivalent to the amount of water that a town populated by upwards of 50,000 people would use in one day. In a 2024 report from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, it estimated that in 2023, the data centers located in the United States consumed 17 billion gallons of water through cooling systems.

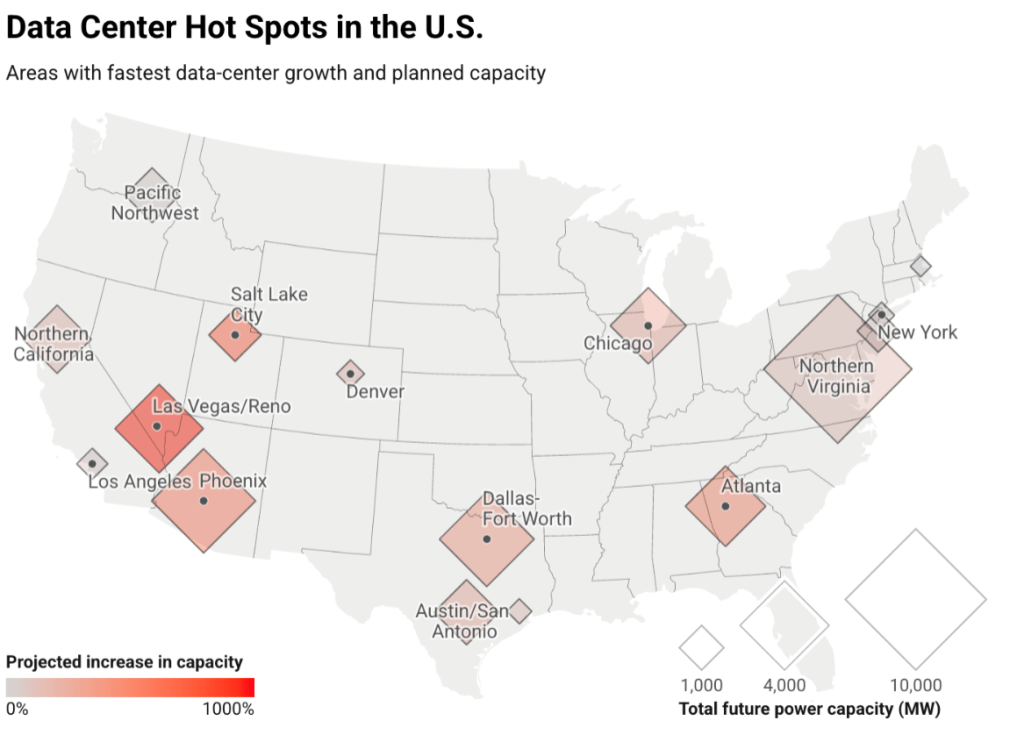

Nearly half of the data centers in the United States are located in water-stressed regions (Figure 3), stressed even further by the indirect uses of water. Worse, only 51% of data centers track their water usage. This translates to a major lack of transparency from companies to the consumers about the irreversible consumption of a shared crucial resource.

Where do we go from here?

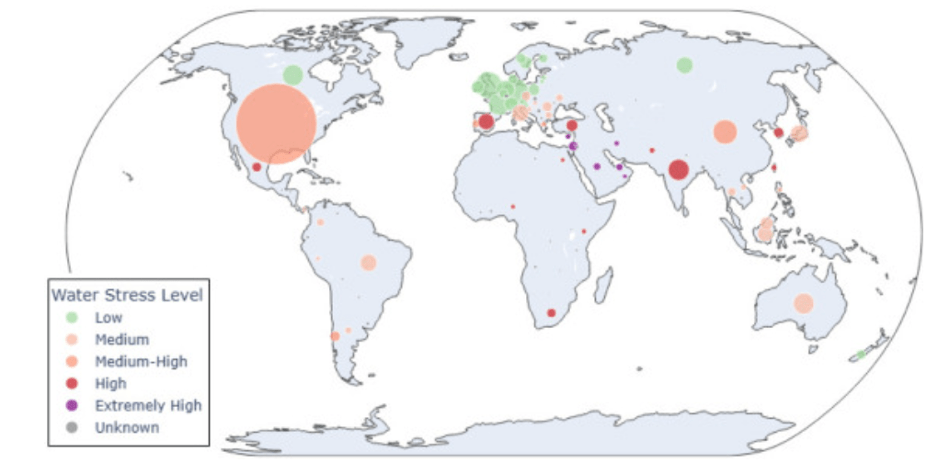

The freshwater that is being consumed by data centers to power gen AI is astronomical – and due to the utter lack of transparency or tracking regulations regarding how much water is being used, we cannot fully evaluate the water cost.

As far as what can be done, it comes down to us – everyday people demanding that changes be made, by policy makers within their own states. To change how water is being used by these data centers, it is imperative that there are standardized protocols put in place to measure the water usage and environmental impact of AI. Regulations need to be developed to track impacts. Algorithms should be made more efficient so they can utilize less electricity and generate less heat (and therefore require less water). The number of data centers will only continue to grow; currently, there are approximately 11,000 data centers worldwide, with just under half of those being present in the United States. Most of those data centers are located in regions already under considerable water stress, putting communities and their environments at risk of being more stressed. If companies continue to blindly and rapidly consume resources without consideration for their negative impacts on communities and their environments – if consumers do not put stress on their policy makers or the companies themselves – companies will continue to build, operate, and run water guzzling data centers in locations in desperate need of clean water (Figure 4)2. And, really, at the end of the day, what is more important: stolen artwork and an easier way to summarize a book, or ensuring that we have a planet to live on with enough water for the people on it?

TL; DR:

- Artificial intelligence has become enmeshed in our society

- Generative AI models such as ChatGPT utilize hundreds of thousands of gallons of freshwater per day which does not get put back into the local water cycle

- Data centers are used to process complex computations required for generate AI and are typically built in water-stressed geographical locations

Reference

- Pollock, L. J., Kitzes, J., Beery, S., Gaynor, K. M., Jarzyna, M. A., Mac Aodha, O., Meyer, B., Rolnick, D., Taylor, G. W., Tuia, D., & Berger-Wolf, T. (2025). Harnessing artificial intelligence to fill global shortfalls in biodiversity knowledge. Nature Reviews Biodiversity, 1(3), 166–182. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44358-025-00022-3

- Herrera, M., Xie, X., Menapace, A., Zanfei, A., & Brentan, B. M. (2025). Sustainable AI infrastructure: A scenario-based forecast of water footprint under uncertainty. Journal of Cleaner Production, 526, 146528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2025.146528