By: Natale Hall

When you hear the words “ocean” and “climate change” together in a sentence, your mind probably jumps to the flashy – and therefore commonly reported climate concerns – like the melting polar ice caps, rising sea levels, more frequent algal blooms, and maybe even coral bleaching. But there’s another, less familiar shift happening below the surface: the ocean is getting darker.

Scientists at the University of Plymouth have found that over one-fifth of the global ocean has dimmed in the past 20 years1. At first, that might not sound alarming. After all, isn’t the ocean already kind of dark? While the open waters may appear so, that darkness is deceiving. In reality, the upper portion of those waters is flooded with sunlight, teeming with life, and crucial for supporting many of the Earth’s functions. So, what does it mean for the ocean to “go dark”? And more importantly, why should we care?

The Photic Zone (And Why it Matters)

When we think about what keeps life on Earth running smoothly, we don’t often consider the layers of the ocean— but we should. The ocean’s surface waters help regulate the planet’s climate, recycle essential nutrients from the atmosphere, and support the vast web of marine life that many ecosystems and people depend on for survival.

Scientists divide the ocean into three zones based on the amount of light penetration through the water: the photic zone, the dysphotic zone, and the aphotic zone2. The photic, or “sunlight,” is the uppermost layer of the ocean that receives sunlight. This zone extends from the water’s surface to a depth of 200 meters, where the sunlight is reduced to about 1% of its surface intensity and beyond which there is little to no light penetration3. 90% of all marine species live in the photic zone, including most of the ocean’s fishes, sharks, turtles, jellyfish, and microscopic plant-like organisms called phytoplankton. Though tiny, phytoplankton are arguably one of the most important life forms on Earth4. Like plants on land, phytoplankton photosynthesize using the available sunlight in the photic zone, and thus accomplish two key things: removing excess carbon dioxide (CO2) and replenishing oxygen (Figure 1).

CO2 is a greenhouse gas that plays a central role in regulating Earth’s climate. By trapping heat in the atmosphere, rising CO2 levels have become one of the primary drivers of global warming5. Each year, phytoplankton remove a net 2-2.5 petagrams of carbon from the air, equivalent to the weight of 10 million blue whales. This accounts for an estimated 30-40% of the global carbon capture, more than the contribution of all terrestrial flora combined, making phytoplankton the major biological force behind balancing atmospheric carbon and controlling the rate of global warming6,7. Beyond carbon capture, phytoplankton also support life on Earth by producing over half of the oxygen in the atmosphere, with some studies suggesting they generate closer to 80% of the total8,9.

As primary producers that create their own food instead of eating other organisms, phytoplankton also form the base of virtually every marine food web. Phytoplankton are consumed by other microorganisms called zooplankton, which are then eaten by small fish, and so on, up the food chain to larger fish, marine mammals, and humans. If there were no phytoplankton, many ocean species would be left without a food source (including those that serve as our food sources!), and the entire system would collapse. Without the photic zone providing a rich environment for phytoplankton to flourish, life on Earth would look very different — and may not exist at all!

The Dimming of Ocean Light

Given recent small-scale reports of dimming ocean light near coasts10,11, and the increasing threat of climate change, researchers at the University of Plymouth investigated how the photic zone has changed over the past two decades on a global scale. These researchers utilized satellite data from NASA’s Ocean Color Web, a program that continuously tracks how sunlight interacts with the ocean surface.1 As light travels through water, it gets absorbed and scattered by water particles and gradually becomes dimmer. This process is called light attenuation (Figure 2). Increased light attenuation means the light fades faster and does not travel as far. Since the Ocean Color Web measures changes in light attenuation across the entire ocean, scientists can estimate how deep sunlight travels through the water and, by extension, the size of the photic zone. In this way, the researchers tracked changes in light attenuation and the photic zone each year from 2003 to 2022, revealing some striking results.

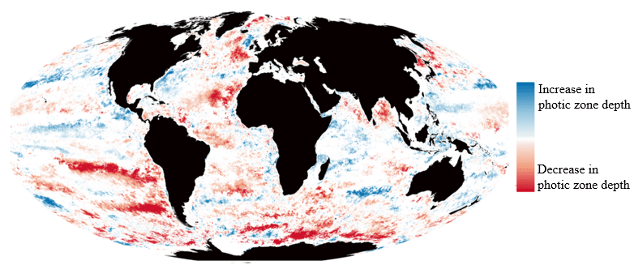

Over the last 20 years, the rate of light attenuation increased across 21% of the ocean, including open-water regions such as the poles, North East Atlantic, and North West Pacific. This means that nearly a quarter of the world’s ocean is getting darker, faster, each year. These findings also translated into shifts in photic zone depth (Figure 3). Across 2.6% of the global ocean, an area nearly the size of the contiguous United States, the photic zone shrank by more than half. In other words, in areas where sunlight once reached depths of 200 meters in 2003, it reached less than 100 meters by 2022.

Now, you may be thinking: 2.6% of the ocean doesn’t sound like much. However, the photic zone also decreased by more than 50 meters across an additional 9% of the ocean, and by over 10 meters across another 19%. Furthermore, the study noted that the satellite measurements are known to undervalue changes in the coastal regions, meaning the photic zone in these regions is likely shallower than reported. This suggests that the true extent of photic zone loss may be even greater than what study reports, making the results even more concerning.

Why is the photic zone shrinking? There are many possibilities. Near the coasts, agricultural runoff and pollution increase the amount of light-blocking sediment and particles in the water. Meanwhile, rising global temperatures are known to intensify harmful algal blooms, which is also likely to cause decreased light penetration in coastal and open waters12. Ocean warming is also known to disrupt the natural circulation of water – prevent mixing – which could cause more sediment and particles to sit on top layers and block light.

Vertical Changes, Global Impacts

As the photic zone shrinks, the space available for phytoplankton and the many other organisms inhabiting the sunlit surface waters is greatly reduced. This seemingly subtle shift in the ocean’s layers could have far-reaching consequences for the climate and the global food web. With less habitat, phytoplankton populations may decline, leading to a drop in oxygen production when, coupled with rising oceanic CO2 may exacerbate ocean acidification7. Such drastic shifts in the atmosphere may accelerate global warming. Moreover, fewer phytoplankton means disrupted marine food chains, which could ultimately impact the availability of the seafood that millions of people and animals depend on.

The darkening of the global ocean isn’t just a change in color – it’s a warning sign. As the photic zone shrinks, the foundation of marine ecosystems and one of our planet’s most powerful climate regulators is being pushed into the shadows. If we want to preserve the brightness of our planet, we can’t afford to let the ocean go dark!

TL; DR

- The photic zone of the ocean is essential to life on Earth

- A recent study found that the photic zone is shrinking, a phenomenon called ocean darkening

- Ocean darkening could have profound consequences on the global food web and climate

Reference

- Davies TW, Smyth T. Darkening of the Global Ocean. Glob Change Biol. 2025;31(5):e70227. doi:10.1111/gcb.70227

- Davies TW, Smyth T. Redefining the photic zone: beyond the autotroph-centric view of light in the ocean. Commun Earth Environ. 2025;6(1):411. doi:10.1038/s43247-025-02374-2

- Ryther JH. Photosynthesis in the Ocean as a Function of Light Intensity. Limnol Oceanogr. 1956;1(1):61-70. doi:10.4319/lo.1956.1.1.0061

- Falkowski P. Ocean Science: The power of plankton. Nature. 2012;483(7387):S17-S20. doi:10.1038/483S17a

- Stips A, Macias D, Coughlan C, Garcia-Gorriz E, Liang XS. On the causal structure between CO2 and global temperature. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):21691. doi:10.1038/srep21691

- Falkowski PG. The role of phytoplankton photosynthesis in global biogeochemical cycles. Photosynth Res. 1994;39(3):235-258. doi:10.1007/BF00014586

- Gruber N, Bakker DCE, DeVries T, et al. Trends and variability in the ocean carbon sink. Nat Rev Earth Environ. 2023;4(2):119-134. doi:10.1038/s43017-022-00381-x

- Sekerci Y, Petrovskii S. Mathematical Modelling of Plankton–Oxygen Dynamics Under the Climate Change. Bull Math Biol. 2015;77(12):2325-2353. doi:10.1007/s11538-015-0126-0

- Yee DP, Samo TJ, Abbriano RM, et al. The V-type ATPase enhances photosynthesis in marine phytoplankton and further links phagocytosis to symbiogenesis. Curr Biol. 2023;33(12):2541-2547.e5. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2023.05.020

- Opdal AF, Lindemann C, Aksnes DL. Centennial decline in North Sea water clarity causes strong delay in phytoplankton bloom timing. Glob Change Biol. 2019;25(11):3946-3953. doi:10.1111/gcb.14810

- Blain CO, Hansen SC, Shears NT. Coastal darkening substantially limits the contribution of kelp to coastal carbon cycles. Glob Change Biol. 2021;27(21):5547-5563. doi:10.1111/gcb.15837

- Gobler CJ, Doherty OM, Hattenrath-Lehmann TK, Griffith AW, Kang Y, Litaker RW. Ocean warming since 1982 has expanded the niche of toxic algal blooms in the North Atlantic and North Pacific oceans. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2017;114(19):4975-4980. doi:10.1073/pnas.1619575114