By: Jenny Lausch

As humans, we are composed of more bacterial cells than human cells.1 These bacteria take up residency in our mouth, skin, and intestines from the day a person is born and establish a cooperative relationship with their human host that allows them to persist over time. These co-evolved strains make up the human microbiome, a compilation of bacteria that live in our bodies and impact our heath. The identity, diversity, and function of the microbes that reside in each individual are highly dependent on our age,2 genetics,3 and arguably most importantly, the dietary choices that we make.4 At almost every turn in the grocery aisle, there is another food product promising to promote “a healthy microbiome” – an enticing, but vague, phrase. A healthy microbiome is most simply defined in three ways: presence of beneficial bacteria,5,6 absence of pathogenic bacteria,7 and high diversity between the species (often referred to as alpha diversity).

Many new therapeutic companies are attempting to formulate the perfect combination of microbes to promote long-term health; however, how the species within the gut microbiome contribute to human health is still an area of ever-evolving science. Unclear about how modulating your gut microbiome composition and function can impact your physiology? Let’s dive into it!

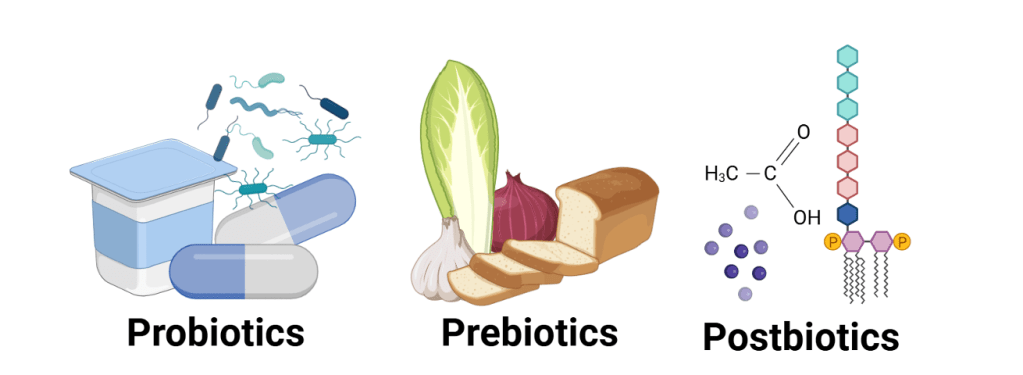

Gut microbial manipulation is typically classified into three broad categories: probiotics, prebiotics, and postbiotics (Figure 1). These terms are all derivatives of the word, “biotic,” which simply means living thing. All these modulators can alter the composition or function of your microbiome, though the efficacy, safety, and financial affordability of each of these biotics varies greatly. By going through each of the terms, we can better understand how to optimize our personal health.

Probiotics: friends for your bacterial community

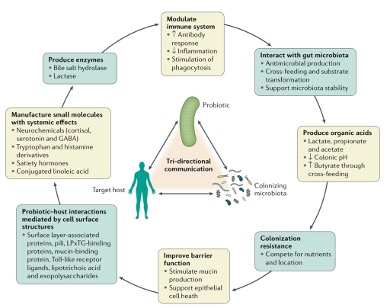

Probiotics are defined as living organisms that can benefit human health. It was initially thought that the only main role of probiotics was to modulate microbe composition by defending against pathogen invasion and increasing the balance of “good” bacteria. However, increased research into the effects of probiotics has revealed a host of mechanisms by which these bacterial strains and their chemical messages, or metabolites, provide a helpful balance to our intestinal ecosystem (Figure 2). Probiotics are consumed via two main routes: fermented foods or encapsulated pills. Fermented foods are generally cheaper than probiotic pills and have live bacterial strains in them; some common examples include yogurt, kombucha, kefir, sauerkraut, kimchi, and sourdough bread (the current social media craze, previously reviewed by another LTS article). Fermented foods take advantage of either environmental microbes or a starter culture to ferment lactose, maltose, or sucrose, which are joined sugars that can quickly be converted into usable energy. Eating fermented foods can lead to less inflammation, better immune defense, and a richer mix of gut microbes.8,9 It is important to check nutritional labels on fermented foods for excess added sugar not used for fermentation, because increased sugar consumption has a myriad of negative effects on your microbiome, such as preventing beneficial species from colonizing your gut and inducing inflammation.5,10,11 Alternatively, we can ingest probiotics by taking pills containing a preselected array of beneficial microbes, usually Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species. Although the consumption of prebiotic pills is generally regarded as safe, it is important to note that because most probiotics are advertised as supplements, they are not typically regulated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) like drugs. This being said, there are a number of scientific studies that have looked at probiotic pills for the treatment of multiple diseases including major depressive disorder,12 ADHD,13 and IBS that have found promising results.14 For example, a meta-analysis comparing the treatment of major depression disorder (MDD) with probiotics or antidepressants found that probiotics were comparable or better than several prescription antidepressants at reducing symptoms and had few side effects. A major challenge with probiotics is determining whether the bacteria in the capsule survive stomach acid and successfully colonize the gut. To improve their chances, early studies are aiming to exploit the unique carbohydrate-degradation capabilities of a prominent beneficial bacterial taxa, Bacteroides, by engineering strains that consume a unique sugar inside seaweed!15 When individuals consume these tailored strains alongside seaweed, researchers can promote selective colonization of these beneficial microbes in the gut.16 Despite all of these exciting findings, most of the foods we consume are not alive, and most graduate students do not have the budget for probiotic supplements, so is there any hope for our microbiomes?

Prebiotics: food for your gut microbes

Luckily, many natural foods contain prebiotics, which are food molecules that cannot be digested by our human cells, but which serve as nutrients for your gut microbiome.18 Humans contain a very limited array of carbohydrate active enzymes, which are proteins that breakdown carbohydrates. As a result, our digestive system can only consume simple sugars (one to two sugars joined together) and very few complex polysaccharides (long chains of sugars), such as starch. However, these indigestible polysaccharides that we eat play an essential role in our health because we have evolved to rely on bacteria to break down many of these polysaccharides that we consume, such as cellulose, pectin, and inulin found in fruits and vegetables. These polysaccharides are found in whole food sources such as onions, artichokes, flaxseed, cashews, and many others act as prebiotics, modulating our microbiome community by serving as a nutrient source for beneficial bacteria. Prebiotics are distinct from the colloquially known fiber.19 The crucial difference between the two is that prebiotics are nutrients that microbes can use to produce energy and grow, whereas fiber is more simply defined as a polysaccharide consisting of more than three subunits that escapes small intestine breakdown.18 Not all gut bacteria can use the same nutrients, so the foods you eat decide which microbes grow—favoring the ones that can make energy from the sugars you consume.15 Despite prebiotics being a food source for bacteria, consuming them is incredibly beneficial to you! Consumption of these prebiotics produces beneficial by-products for human health and is referred to as fermentation.20 These by-products or compounds are typically referred to as postbiotics and are the topic of our next section.

Table 1. Types of prebiotic fibers and what foods they are commonly found in. Adapted from oralhealthgroup.com.

| Prebiotic Type | Food Source |

| Fructans (Inulin, FOS) | Artichoke, garlic, onions, leek, asparagus, banana |

| Galactooligosaccharides | Chickpeas, beans, lentils, broccoli, brussels sprouts |

| Resistant Starch | Plantains, cooked and chilled potatoes and rice, oatmeal, beans, peas |

| Beta-Glucan | Oatmeal, barley, mushrooms, yeast, seaweed |

| Polyphenols | Berries, tea, dark chocolate, red onion, spinach, broccoli, herbs, and spices |

Postbiotics: fighters against host disease

Postbiotics are metabolites, produced or derived from bacteria that allow bacteria to communicate with each other and modulate positive host responses. This includes prebiotic fermentation products and cell debris that are produced when bacteria die or in response to stress.21. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) are a type of bacterial metabolite and prime energy source produced when bacteria consume fiber. These chemicals are essential to host (human) physiology because they serve as a major nutrient source for intestinal cells, subsequently strengthening the protective layer of the colon that seperates microbes and toxins from the immune system. Additionally, SCFAs can increase natural glucagon-like-peptide 1 (GLP-1) release, a hormone important for regulating blood sugar and metabolism.6,21 Additionally, SCFAs may even display an anti-tumorigenic effects by promoting death in colon cancer cells or modulate brain function by affecting the gut-brain axis.22,23 Although how SCFAs specifically affect the gut-brain axis, the two-way communication between our central nervous system and enteric nervous system, is largely unknown, researchers suggest that SCFAs may increase signaling between these two systems, increase the production of regulatory T cells that fight inflammation, and induce the production of hormones that increase, cognition and mood.23,24

Due to their direct effects on the host, direct postbiotic supplementation has been suggested as a potential therapeutic for obesity, depression, and colitis and may be the medicine of the future for other diseases.25–27

Together, pro-, pre-, and postbiotic consumption provides a powerful synergy to modulate gut microbiome composition and function. By consuming a diverse array of plant sources and fermented foods, we can support a healthy microbiome that subsequently promotes a long, healthy life.

TL; DR:

- Probiotics are consumable live bacteria

- Prebiotics are bacteria-accessible nutrients present in whole food sources

- Postbiotics are beneficial, bacterial-derived chemical messages

- Together, these -biotics can promote human health by modulating the microbiome

Reference

- Ley, R. E., Peterson, D. A. & Gordon, J. I. Ecological and Evolutionary Forces Shaping Microbial Diversity in the Human Intestine. Cell 124, 837–848 (2006).

- Olm, M. R. et al. Robust variation in infant gut microbiome assembly across a spectrum of lifestyles. Science 376, 1220–1223 (2022).

- Goodrich, J. K. et al. Genetic Determinants of the Gut Microbiome in UK Twins. Cell Host & Microbe 19, 731–743 (2016).

- David, L. A. et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature 505, 559–563 (2014).

- Wegorzewska, M. M. et al. Diet modulates colonic T cell responses by regulating the expression of a Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron antigen. Sci Immunol 4, eaau9079 (2019).

- Furusawa, Y. et al. Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature 504, 446–450 (2013).

- Desai, M. S. et al. A Dietary Fiber-Deprived Gut Microbiota Degrades the Colonic Mucus Barrier and Enhances Pathogen Susceptibility. Cell 167, 1339-1353.e21 (2016).

- Wastyk, H. C. et al. Gut-microbiota-targeted diets modulate human immune status. Cell 184, 4137-4153.e14 (2021).

- Spencer, S. P. et al. Fermented foods restructure gut microbiota and promote immune regulation via microbial metabolites. 2022.05.11.490523 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.11.490523 (2022).

- Pearce, V. H., Groisman, E. A. & Townsend, G. E. Dietary sugars silence the master regulator of carbohydrate utilization in human gut Bacteroides species. Gut Microbes 15, 2221484 (2023).

- Khan, S. et al. Dietary simple sugars alter microbial ecology in the gut and promote colitis in mice. Sci Transl Med 12, eaay6218 (2020).

- Zhao, S. et al. Probiotics for adults with major depressive disorder compared with antidepressants: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Nutr Rev 83, 72–82 (2025).

- Allahyari, P. et al. A systematic review of the beneficial effects of prebiotics, probiotics, and synbiotics on ADHD. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep 44, 300–307 (2024).

- Wu, Y., Li, Y., Zheng, Q. & Li, L. The Efficacy of Probiotics, Prebiotics, Synbiotics, and Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 16, 2114 (2024).

- Shepherd, E. S., DeLoache, W. C., Pruss, K. M., Whitaker, W. R. & Sonnenburg, J. L. An exclusive metabolic niche enables strain engraftment in the gut microbiota. Nature 557, 434–438 (2018).

- Whitaker, W. R. et al. Controlled colonization of the human gut with a genetically engineered microbial medicine. 2024.10.03.24314621 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.10.03.24314621 (2024).

- Sanders, M. E., Merenstein, D. J., Reid, G., Gibson, G. R. & Rastall, R. A. Probiotics and prebiotics in intestinal health and disease: from biology to the clinic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 16, 605–616 (2019).

- Davani-Davari, D. et al. Prebiotics: Definition, Types, Sources, Mechanisms, and Clinical Applications. Foods 8, 92 (2019).

- Slavin, J. Fiber and Prebiotics: Mechanisms and Health Benefits. Nutrients 5, 1417–1435 (2013).

- Caffrey, E. B., Sonnenburg, J. L. & Devkota, S. Our extended microbiome: The human-relevant metabolites and biology of fermented foods. Cell Metabolism 36, 684–701 (2024).

- Żółkiewicz, J., Marzec, A., Ruszczyński, M. & Feleszko, W. Postbiotics—A Step Beyond Pre- and Probiotics. Nutrients 12, 2189 (2020).

- Cousin, F. J., Jouan-Lanhouet, S., Dimanche-Boitrel, M.-T., Corcos, L. & Jan, G. Milk Fermented by Propionibacterium freudenreichii Induces Apoptosis of HGT-1 Human Gastric Cancer Cells. PLOS ONE 7, e31892 (2012).

- Dalile, B., Van Oudenhove, L., Vervliet, B. & Verbeke, K. The role of short-chain fatty acids in microbiota–gut–brain communication. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 16, 461–478 (2019).

- Arpaia, N. et al. Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation. Nature 504, 451–455 (2013).

- Fang, W., Xue, H., Chen, X., Chen, K. & Ling, W. Supplementation with Sodium Butyrate Modulates the Composition of the Gut Microbiota and Ameliorates High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity in Mice. J Nutr 149, 747–754 (2019).

- Lee, J. G. et al. Impact of short-chain fatty acid supplementation on gut inflammation and microbiota composition in a murine colitis model. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 101, 108926 (2022).

- Firoozi, D., Masoumi, S. J., Mohammad-Kazem Hosseini Asl, S., Fararouei, M. & Jamshidi, S. Effects of Short Chain Fatty Acid-Butyrate Supplementation on the Disease Severity, Inflammation, and Psychological Factors in Patients With Active Ulcerative Colitis: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. J Nutr Metab 2025, 3165876 (2025).