By Zoe Katz

The measles virus is one of the oldest viruses to exist on this planet 1. An ancient disease, measles was first described in the ninth century by a renowned Persian physician and scholar named Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakariyya al-Razi. In his landmark “A Treatise on the Small-Pox and Measles” 2, al-Razi, masterfully and for the first time in recorded medicine, distinguished between the clinical presentations of smallpox and measles 3,4, allowing physicians to develop distinct treatments for the two. His descriptions, made over two millennia ago, laid the foundation for efforts to eradicate measles.

In the decade before the measles vaccine was developed, nearly all children would become infected. Common symptoms included a high fever, cough, and tell-tale red rash spreading from the head to the rest of the body. In some cases, severe complications arose such as pneumonia, encephalitis (or swelling of the brain), and death in 1-3% of children infected. Complications from encephalitis acquired during infection could lead to convulsions and result in the child becoming deaf or having cognitive disabilities. Following the development of a vaccine in 1968, a highly effective vaccination program led to measles being declared eradicated in the United States 25 years ago; since then, however, measles cases have steadily been rising (Figure 1). Devastatingly, there are now three casualties, the first to occur in ten years. The first death was that of an unvaccinated school-aged child in Texas in February; the second was an unvaccinated adult in New Mexico; the third happened on April 6th, a school-aged child who was also unvaccinated. These deaths are due to a decrease in the percentage of people who are vaccinated 5 and particularly due to an outbreak in a Mennonite community in Texas where vaccination rates are low.

A decrease in measles vaccinations is dangerous – it can lead to widespread infection in vulnerable populations, which can be deadly. For survivors, there is the threat of “immune amnesia,” which describes the ability of the measles virus to “reset” (like a memory wipe) the arm of the immune system which remembers previous infections. When we get infected with a virus or bacterium, our immune system immediately starts fighting back to get said infection under control. After the infection is cleared, our immune system is able to generate a memory against those pathogens, meaning that if we ever get infected again, we are able to respond faster and fight infection better. The danger of measles virus infection is its ability to get rid of that immunological memory for every pathogen that we have encountered previously. This destruction leaves those who were not vaccinated previously against measles in dangerous waters. Understanding the danger that this virus causes and how vaccinations prevent this danger will take us, as a whole, one step closer to once more achieving its eradication.

Why vaccination against measles matters

The measles virus spreads through respiratory droplets, which are made when a person coughs or sneezes 6. Once an infected person leaves an area, the virus can linger in the air for up to two hours. If an unvaccinated person breathes in these respiratory droplets, they may become infected. And, as one of the most contagious viruses out there, one person infected with measles will result in nine out of ten unvaccinated people to become infected. In comparison, one person infected with the flu will infect one or two other people. To prevent the unencumbered spread of this virus through communities, which is presently occurring throughout the United States and the world, it is extremely important to have herd immunity.

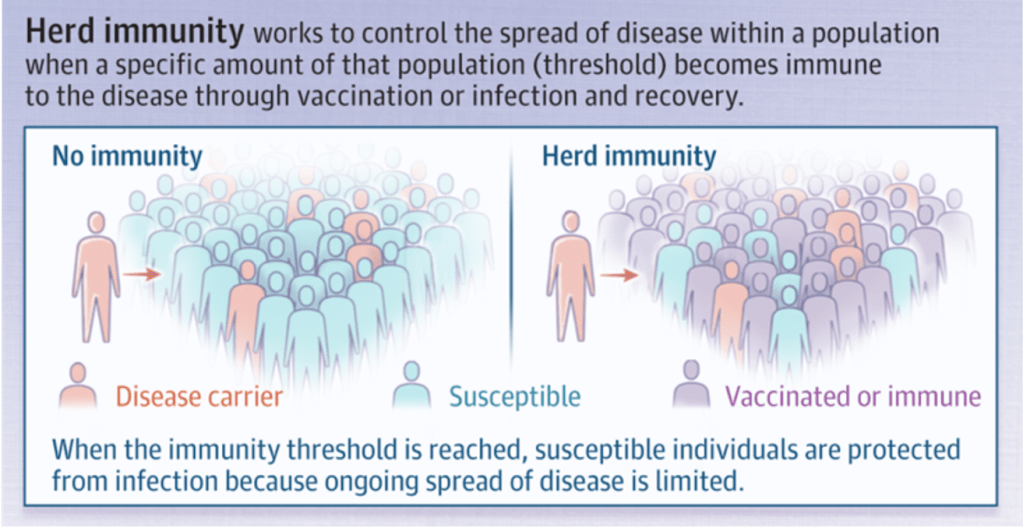

Herd immunity refers to when a large percentage of a population is immunized and, therefore, protected against infection with a pathogen, indirectly protecting people who are unable to be vaccinated, including those who are immunocompromised and under one year of age. Therefore, getting vaccinated is beneficial, not only for the person getting the vaccine, but also to protect those that are unable to safely be vaccinated. (Figure 2) 7. Obtaining high levels of immunity for a virus like the measles virus is extremely necessary to prevent uncontrollable spread. The percentage of vaccinated people needs to reach or exceed 95% of the population for herd immunity to be effective and prevent virus spread in a given community, simply because of how contagious the virus is. Thus, herd immunity is imperative for protection against measles.

Getting vaccinated with the Measles, Mumps, and Rubella vaccine (commonly referred to as the MMR vaccine) is the best way to protect oneself from measles infection 8. Currently, the best way to prevent infection is receiving two doses of the MMR vaccine. The first dose is typically given when a child is 12-15 months old, and the second, when they are 4-6 years old. One dose of the MMR vaccine is 93% effective in protecting against measles infection, while the one-two punch of both doses is 97% effective 8. Once administered, this vaccine usually protects people for their entire lives.

What does it mean to have “protection” against the measles virus? How does the MMR vaccine induce protection?

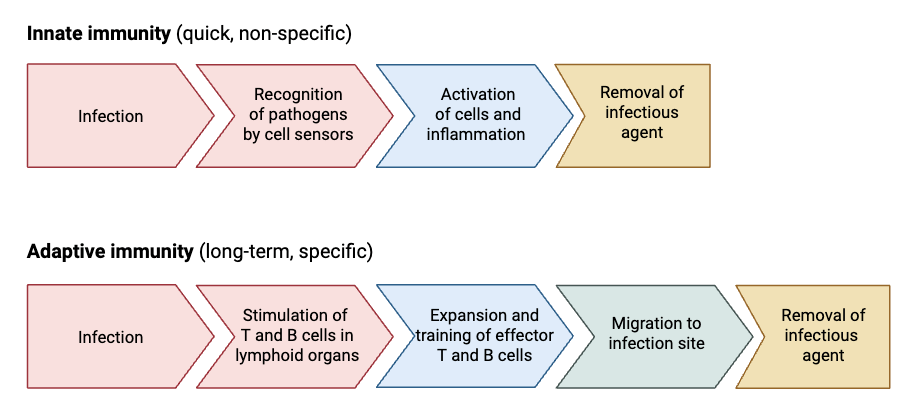

To understand how vaccines work, it is imperative to understand how our immune system functions. The immune system is a complex network of molecules, cells, and organs that work together to protect someone from invading pathogens (microorganisms such as viruses that cause disease). Making up the immune system are two “arms” of protection (Figure 3) – these are innate immunity (generalized defenses) and adaptive or acquired immunity (designed to fight against a specific pathogen with both T cells and B cells). Whereas the innate response is mounted within minutes to hours after infection 9, the adaptive immune response can take days to weeks 10,11.

For viruses to enter and infect cells, a protein on the virus surface must bind to a receptor on a cell. To prevent this, B cells make small proteins called antibodies which bind to (or stick to) the protein on the surface of the virus, effectively preventing infection by blocking access to this critical structure 12. If viruses are able to infect cells despite these first defenses, T cells take over the fight. T cells can recognize when cells are infected and are able to kill them, keeping virus spread under control by taking infected cells out of the equation 13.

For the MMR vaccine (and others) to be protective, it must allow for the generation and maintenance of immunological memory. Memory T cells and B cells are generated during initial viral infections and after vaccination 6,7,14 because immunizations act like a first infection without all of the dangers that come with it. They remain present in the body, ready to quickly fight and protect against future subsequent infections with the same pathogen 15. Memory can last years after an infection has been cleared.

The measles virus wipes the immune system’s ability to fight against other pathogens

The immune response generated against an infection with measles virus is strong, effective, and – for survivors of infection – life-long. This immunity is composed of both T and B cells that have the ability to fight against reinfection. However, with this survival and immunity against future measles infection comes a heavy cost: it is also associated with systemic immune suppression against other pathogens 6. Indeed, the dangers of this are highlighted by the main causes of measles mortality being infections that occur after measles infection has ended, primarily affecting the respiratory and digestive tracts 13. The immune suppression that is seen after infection with measles is extremely dangerous – it destroys the immune system’s ability to protect against pathogens it has seen and developed immunity to in the past 6. This phenomenon is called immune amnesia.

What is immune amnesia and how does it happen?

During an immune response, T cells become activated, acting quickly to kill infected cells. B cells work to prevent further infection. During this phase they are called “effector” cells. Following the clearance of infection, a large portion of them die off – we don’t want to have too many cells around that kill! The small portion of cells that don’t die differentiate into “memory” cells (Figure 4) 10,15. They remain present in the body, primed and ready to respond even faster than before should a reinfection with the same pathogen occur (because they’ll know the danger when they see it). Memory cells are made after every infection and can be made after vaccinations, as is seen with measles virus infection and immunization.

Viruses often target specific subsets of the body’s cells; this preference is called “viral tropism,” and the viral tropism – cell preference – of measles virus is what makes it so dangerous. 17. The virus infects memory immune cells 6. When measles virus infects the body – and in this case, targets T and B cells – T cells are responsible for killing those infected cells (even though those cells are members of their own little anti-virus army). They become aware that memory T and B cells are infected and kill them like an assassin. In doing so, memory T and B cells generated against any other pathogen that once infected the host (i.e., you) are destroyed, obliterating any lasting protection against any other virus or microbe 6,16. Referred to as the measles paradox, however, is the fact that despite the devastation the virus causes to the memory generated against other viruses, the memory generated to fight against subsequent measles virus infections is life-long and extremely protective 6.

A majority of people who were both unvaccinated and previously infected with the measles virus die later from another infection, called an opportunistic infection 6,13,16. Immune amnesia and the resulting morbidity very rarely occur in vaccinated people. So: it is an extremely dangerous threat, though preventable. With administration of two doses of the MMR vaccine, one can generate life-long immunity against measles without jeopardizing the rest of the immune system.

The trust in vaccine safety has decreased, increasing preventable death.

The rise in measles cases and occurrence of three deaths, the first in ten years, does not come out of nowhere. The opposition to vaccines has been around since they were first made and introduced back in the 1800s by Edward Jenner and continue, dangerously, to this day. But the lack of trust in the MMR vaccine stems from a much more recent controversy.

In 1998, the journal The Lancet (a high impact, peer-reviewed journal) published the seminal research paper, “Illeal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children”. In this paper, now-disgraced doctor and current anti-vaccine advocate Andrew Wakefield purported that he found a link between the administration of the MMR vaccine and the development of autism. This article turned thousands of parents away from getting their children vaccinated against measles, mumps, and rubella.

As was later found, this paper has major issues. The first comes from the study design and subjects themselves. The cohort (group of people being studied) was very small – only twelve people were part of this study, and eleven of them were males. Even more worrying is the fact that the behavioral symptoms observed were reported by the parents of the children in the study, not doctors themselves. Also, it was uncovered in 2010 that some of the research funding came directly from lawyers who were involved in pursuing vaccine manufacturers in court. Worst of all, children of families involved in these lawsuits were the same children in the cohort studied, which should have disqualified them from participating altogether. Over the next ten years, fully controlled, properly set-up epidemiological studies consistently found no link between autism and the MMR vaccine. All of this together led to the Wakefield paper being retracted, or permanently removed from the journal it was published in, in 2010, twelve years after it was published. But the damage was already done. The article’s “findings” were given a spotlight. The damage to global public health continues and heightens to this day, showcased by increasing cases, outbreaks, and deaths in Texas among our countries most vulnerable – children.

TL; DR

- Though once eradicated in the United States, measles cases are now on the rise, with three deaths resulting from lack of vaccination.

- Dangerously, infection with measles causes “immune amnesia” where the virus kills immune cells that remember all past infections with any virus.

- Immune amnesia leads to increased mortality after one is infected with another pathogen, which does not occur in vaccinated people.

Reference

- Düx, A. et al. Measles virus and rinderpest virus divergence dated to the sixth century BCE. Science 368, 1367–1370 (2020).

- Hajar, R. The air of history (Part IV): Great Muslim physicians Al Rhazes. Heart Views 14, 93 (2013).

- Berche, P. History of measles. La Presse Médicale 51, 104149 (2022).

- Amr, S. S. & Tbakhi, A. Abu Bakr Muhammad Ibn Zakariya Al Razi (Rhazes): Philosopher, Physician and Alchemist. Annals of Saudi Medicine 27, 305–307 (2007).

- Pandey, A. & Galvani, A. P. Exacerbation of measles mortality by vaccine hesitancy worldwide. The Lancet Global Health 11, e478–e479 (2023).

- Moss, W. J. & Griffin, D. E. What’s going on with measles? J Virol 98, e00758-24 (2024).

- Gans, H. A. et al. Measles humoral and cell-mediated immunity in children aged 5-10 years after primary measles immunization administered at 6 or 9 months of age. J Infect Dis 207, 574–582 (2013).

- Strebel, P. M. & Orenstein, W. A. Measles. N Engl J Med 381, 349–357 (2019).

- Marshall, J. S., Warrington, R., Watson, W. & Kim, H. L. An introduction to immunology and immunopathology. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 14, 49 (2018).

- Netea, M. G., Schlitzer, A., Placek, K., Joosten, L. A. B. & Schultze, J. L. Innate and Adaptive Immune Memory: an Evolutionary Continuum in the Host’s Response to Pathogens. Cell Host & Microbe 25, 13–26 (2019).

- Chaplin, D. D. Overview of the immune response. J Allergy Clin Immunol 125, S3-23 (2010).

- Pantaleo, G., Correia, B., Fenwick, C., Joo, V. S. & Perez, L. Antibodies to combat viral infections: development strategies and progress. Nat Rev Drug Discov 21, 676–696 (2022).

- De Vries, R. D. et al. Measles Immune Suppression: Lessons from the Macaque Model. PLoS Pathog 8, e1002885 (2012).

- Wang, L. et al. Associations of adaptive immune cell subsets with measles, mumps, and Rubella−Specific immune response outcomes. Heliyon 9, e22998 (2023).

- Lam, N., Lee, Y. & Farber, D. L. A guide to adaptive immune memory. Nat Rev Immunol 24, 810–829 (2024).

- Laksono, B. M. et al. Studies into the mechanism of measles-associated immune suppression during a measles outbreak in the Netherlands. Nat Commun 9, 4944 (2018).

- Nomaguchi, M., Fujita, M., Miyazaki, Y. & Adachi, A. Viral tropism. Front Microbiol 3, 281 (2012).