By Makenzie Nolt

While watching the news or reading about current events, you may have heard of Mad Cow or Chronic Wasting Disease in deer. Although these are two different conditions, they both result from misfolded proteins called prions1. Prion diseases are not exclusive to livestock; humans can also be affected by prion diseases such as Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), Fatal Familial Insomnia (FFI), or Kuru2. Research has indicated that prion-like protein misfolding may also play a role in common neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease3. Although these diseases are well-studied, exactly how and why they develop remains unknown4. Could prions provide the answer to these mysterious disease origins?

How does the brain normally function?

To understand the impacts of protein misfolding on the brain, it is important to understand how the brain functions normally. The brain is an incredibly complex and mysterious organ that cannot be discussed in full detail in this article; however, there is an important cell type to mention –neurons. Neurons are the cells responsible for generating and transmitting the electrical and chemical signals that are critical for proper brain function, including communication between different parts of the brain. The chemical signals that neurons use to communicate are called neurotransmitters. Examples of neurotransmitters include glutamate, GABA, dopamine, and serotonin22. When neurotransmitter release is disrupted and neurons cannot communicate properly, such as in the case of prion or neurodegenerative diseases, there can be disturbances to motor function, cognition, and memory.

How do prions form?

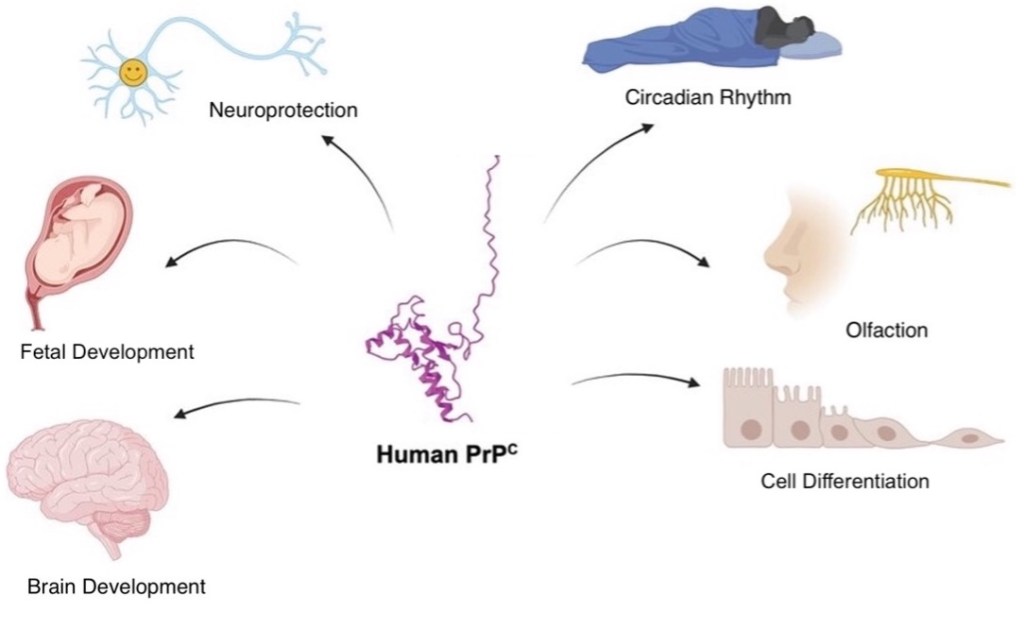

Although the function of cellular prion protein (PrPC) is unknown, PrPC is suspected to be involved in many important processes such as neuroprotection, regulating the circadian rhythm, and promoting cell survival (Figure 1)5. PrPC is present in most cells20, although it is largely concentrated in neurons6. When PrPC is misfolded, it becomes prion protein scrapie (PrPSc), the “sticky”, disease-causing form that leads to the formation of toxic aggregates by converting PrPC to PrPSc and slowly eliminating the native form5. The resulting toxic aggregates, called ‘prions’, lead to neurodegeneration associated with CJD, FFI, and Kuru5,6. As mentioned, protein misfolding is also known to occur in common forms of neurodegeneration like Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease5,6. Therefore, understanding how protein misfolding contributes to both prion diseases and neurodegeneration could lead to the development of live-saving therapeutics.

What causes prion diseases?

Depending on the cause, the development of prion diseases such as Fatal Familial Insomnia (FFI) and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) can be categorized as sporadic, genetic, or acquired2,8. Genetic diseases usually occur from mutations, or changes, in DNA. For example, FFI is most commonly genetic and is caused by a mutation in the PRNP gene, which encodes PrPC. FFI is quite rare, with only about 100 cases reported across 40 families globally2,8. In contrast to genetic diseases, acquired diseases have a designated environmental cause. Acquired CJD is even more rare than FFI and has been caused by contaminated medical equipment or growth hormone treatments using samples from infected deceased individuals2. Sporadic prion diseases are difficult to characterize, most likely because both genetics and environment play a role. For example, sporadic CJD (sCJD) occurs randomly with no known cause with only 1-2 million cases in the global population8. sCJD presents with rapid progression of dementia, along with balance, speech, and visual issues8. Sporadic fatal insomnia (sFI), in contrast to FFI, can develop without mutation to the PRNP gene. The symptoms of FFI and sFI are similar including recurrent insomnia, speech issues, and loss of motor coordination8. Although there are various causes for prion diseases, the overall likelihood of developing one is exceedingly rare compared to more common neurodegenerative diseases, even though protein misfolding is a hallmark of both.

Prion-like nature of common neurodegenerative diseases.

ore than 50 million people are affected by neurodegenerative diseases worldwide, and that number is expected to triple to 152 million by 2050 if effective therapeutics are not discovered7. The most common neurodegenerative diseases are Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) and Parkinson’s Disease (PD)9 These diseases have been studied for decades but there are still plenty of unanswered questions. What initiates the cascade of events resulting in each disease? Could it be genetic, environmental, age, or just ‘luck’ of the draw? More specifically, could they be caused by the misfolding of proteins, like PrPC in prion diseases?

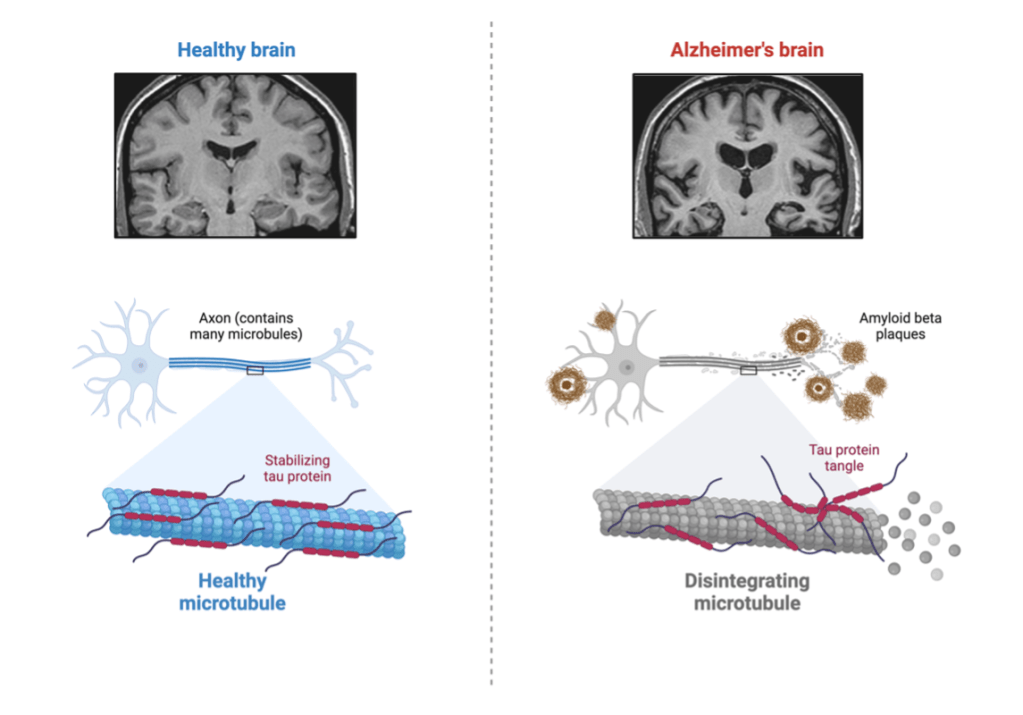

Nearly 7 million individuals over the age of 65 are affected with AD10. AD causes neuron cell death in regions of the brain associated with memory, language, and cognitive function. Some of the first symptoms of AD are forgetting events or misplacing objects, becoming disorganized, and getting lost10. Two culprits for the development of AD are amyloid beta (Aβ) and tau. Aβ is a protein associated with neuronal cell growth and protecting the body from infection. Tau helps to stabilize microtubules to provide cell structure12. As seen in figure 2, during AD, these proteins accumulate into Aβ plaques and tau tangles that cause neuronal cell damage, resulting in the neurologic disturbances mentioned 7,10. Similar to AD, PD usually affects individuals in their 60s-70s. PD causes hand tremors, muscle rigidity, balance issues, and eventual cognitive decline13. PD is also associated with Aβ plaques and tau tangles, along with another protein called ⍺-synuclein (⍺-syn). ⍺-syn is associated with the release of dopamine, a neurotransmitter important for motor function. When ⍺-syn becomes misfolded, it accumulates into toxic Lewy-bodies, resulting in decreased dopamine that causes the motor disturbances characteristic of PD. (Figure 3)13. What initiates the misfolding of proteins in AD and PD is unknown, but the parallel of toxic protein aggregation in prion diseases can’t be ignored14,15.

Adding weight to the prion-like nature of neurodegenerative diseases, there was a recent study published in Nature Medicine discussing acquired Alzheimer’s disease16. Children who received growth hormone from cadavers, a practice banned in the 1980s, went on to develop Alzheimer’s disease believed to be from the transmission of Aβ16. This form of transmission has been established in acquired Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD)2, but not in common neurodegenerative diseases. These findings may sound alarming but there is no need to worry about “catching” Alzheimer’s disease. This was an exceedingly rare case of neurodegenerative disease development. Nonetheless, the findings highlight the prion-like nature of Aβ in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease16.

What does this mean for the future of neurodegenerative diseases?

Currently, there is no cure for prion or neurodegenerative diseases; however, there is active research to identify treatments by targeting aggregating proteins using antibodies17,18. Antibodies are small proteins usually produced by the immune system that bind to and help eliminate unwanted substances from the body. There are two antibodies on the market, lecanemab and aducanumab, to treat AD17. Lecanemab prevents the conversion of Aβ into aggregates and aducanumab targets the aggregates themselves. Both drugs help slow the progression of cognitive decline in AD17. Other types of drugs such as carbidopa and levodopa target the symptoms of PD by aiding in the production of dopamine, reducing the effects of motor disturbances18.

As of now, there are no drugs that specifically target protein misfolding in AD and PD; however, a compound found in green tea, epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), appears to target protein misfolding and might be a potential therapeutic option. More research is needed to determine the efficacy of EGCG in neurodegenerative diseases21. While there may not be an AD or PD specific drug that targets protein misfolding, there is one to treat a different neurodegenerative disease. The drug Vyndamax (tafamidis) targets protein misfolding in a rare neurodegenerative disease called transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy that is caused by the misfolding of transthyretin (TTR) protein. Vyndamax binds to TTR and stabilizes it to prevent misfolding, slowing progression and disease burden19. Vyndamax could be a model for other therapeutics that target protein misfolding in prion and neurodegenerative diseases.

Overall, the link between prion and neurodegenerative diseases suggests shared similarities between the two. A leading cause of both appears to be toxic protein misfolding primarily in neurons, disrupting communication within the brain. Prion and neurodegeneration diseases also have diverse risk factors, both genetic and environmental. Moreover, these diseases typically occur later in life and present with similar symptoms. Currently there is no treatment for prion diseases, but therapeutics are available for AD and PD; however, none specifically target protein misfolding. More research is needed to fully understand the potential link and complex nature of these diseases, leading to the development of new therapeutics and potentially longer lives with less impairment.

TL; DR

- Prion diseases are caused by misfolded proteins that share several commonalities with neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease.

- Understanding the commonalities between neurodegenerative and prion diseases could lead to the development of improved therapeutics.

Reference

- Haley, N. J. & Richt, J. A. Classical bovine spongiform encephalopathy and chronic wasting disease: two sides of the prion coin. Animal Diseases 3, 24 (2023).

- Baiardi, S., Mammana, A., Capellari, S. & Parchi, P. Human prion disease: molecular pathogenesis, and possible therapeutic targets and strategies. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets 27, 1271–1284 (2023).

- Prusiner, S. B. Biology and Genetics of Prions Causing Neurodegeneration. Annual Review of Genetics 47, 601–623 (2013).

- Wareham, L. K. et al. Solving neurodegeneration: common mechanisms and strategies for new treatments. Molecular Neurodegeneration 17, 23 (2022).

- Eid, S. et al. The importance of prion research. Biochem. Cell Biol. 102, 448–471 (2024).

- Hirsch, T. Z., Hernandez-Rapp, J., Martin-Lannerée, S., Launay, J.-M. & Mouillet-Richard, S. PrPC signalling in neurons: From basics to clinical challenges. Biochimie 104, 2–11 (2014).

- Passeri, E. et al. Alzheimer’s Disease: Treatment Strategies and Their Limitations. Int J Mol Sci 23, 13954 (2022).

- Imran, M. & Mahmood, S. An overview of human prion diseases. Virology Journal 8, 559 (2011).

- Han, Z. et al. Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease: a Mendelian randomization study. BMC Med Genet 19, 215 (2018).

- Li, X. et al. Global, regional, and national burden of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, 1990–2019. Front. Aging Neurosci. 14, (2022).

- Brothers, H. M., Gosztyla, M. L. & Robinson, S. R. The Physiological Roles of Amyloid-β Peptide Hint at New Ways to Treat Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Aging Neurosci 10, 118 (2018).

- Michalicova, A., Majerova, P. & Kovac, A. Tau Protein and Its Role in Blood–Brain Barrier Dysfunction. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 13, (2020).

- Kouli, A., Torsney, K. M. & Kuan, W.-L. Parkinson’s Disease: Etiology, Neuropathology, and Pathogenesis. in Parkinson’s Disease: Pathogenesis and Clinical Aspects (eds. Stoker, T. B. & Greenland, J. C.) (Codon Publications, Brisbane (AU), 2018).

- Stopschinski, B. E. & Diamond, M. I. The prion model for progression and diversity of neurodegenerative diseases. The Lancet Neurology 16, 323–332 (2017).

- Walker, L. C. & Jucker, M. Neurodegenerative Diseases: Expanding the Prion Concept. Annual Review of Neuroscience 38, 87–103 (2015).

- Banerjee, G. et al. Iatrogenic Alzheimer’s disease in recipients of cadaveric pituitary-derived growth hormone. Nat Med 30, 394–402 (2024).

- Cummings, J., Osse, A. M. L., Cammann, D., Powell, J. & Chen, J. Anti-Amyloid Monoclonal Antibodies for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. BioDrugs 38, 5–22 (2024).

- Muranova, A. & Shanina, E. Levodopa/Carbidopa/Entacapone Combination Therapy. in StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL), 2025).

- Morfino, P. et al. Transthyretin Stabilizers and Seeding Inhibitors as Therapies for Amyloid Transthyretin Cardiomyopathy. Pharmaceutics 15, 1129 (2023).

- Martellucci, S. et al. Prion Protein in Stem Cells: A Lipid Raft Component Involved in the Cellular Differentiation Process. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21, 4168 (2020).

- Gonçalves, P. B., Sodero, A. C. R. & Cordeiro, Y. Green Tea Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) Targeting Protein Misfolding in Drug Discovery for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Biomolecules 11, 767 (2021).

- Hyman, S. E. Neurotransmitters. Current Biology 15, R154–R158 (2005).

I was living a normal life with my family when, at 52, I began experiencing muscle stiffness and twitching. After seeing a neurologist, I was diagnosed with ALS. It was a tough reality, and as the disease progressed, I eventually lost the ability to walk and relied on a wheelchair. A friend recommended EarthCure Herbal Clinic (www. earthcureherbalclinic .com), where I began treatment under Dr. Madida Sam. After about three months, I noticed significant improvements, less stiffness, fewer symptoms, and I was able to walk distances again.