By: Marissa Padilla and Julia Simpson

Today, we have vaccines available for various pathogens (disease-causing agents) that have historically plagued mankind, including measles, tetanus, the flu, and most recently, COVID-19. Vaccines are our best form of defense against deadly pathogens because they teach our immune system to create small proteins, called antibodies, that help neutralize pathogens. Scientists are always searching for new, creative ways to vaccinate people more effectively against pathogens, but the process of designing, testing, and implementing a new vaccine is long and extensive.

In today’s world, misinformation about vaccine development and safety is widespread, despite the fact that vaccines undergo rigorous safety and efficacy trials prior to approval for us. This article aims to educate readers about vaccine development, and to highlight an interesting clinical trial: one where scientists attempted to pioneer a way to use mosquitoes to deliver a vaccine into people, but later adapted their approach to create the safest possible vaccine – showcasing the rigorous vaccine development process working precisely as it should in pursuit of a safer, healthier world.

Vaccines undergo rigorous clinical trials

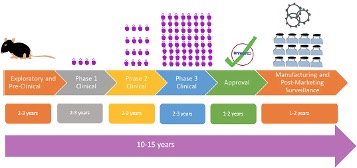

Overall, vaccine development – and approval of the final vaccine – takes years. First, potential vaccine candidates are experimentally tested in cell and animal models to see if the vaccine can elicit an effective immune response. This preclinical process takes 2-3 years and is conducted by drug companies or in collaboration with academic institutes (Figure 1). Only once sufficient data is obtained can a promising vaccine candidate be identified; at this step, the work gets submitted to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) seeking approval to conduct a human clinical trial9.

After preclinical data is approved, companies will conduct clinical trials using human volunteers to understand the overall effectiveness in preventing disease and safety of the vaccine. These trials occur in three phases9:

- Phase 1: The vaccine is administered to 20-100 healthy volunteers to assess the safety of the vaccine and identify side effects.

- Phase 2: The number of volunteers increases to 100-300 people, similar in age and health to the vaccine’s target population. This reaffirms the vaccine’s safety and evaluates its ability to elicit an immune response9.

- Phase 3: Aims to monitor safety and effectiveness among thousands of individuals receiving the vaccine compared to a placebo (a treatment that appears real but does not have a therapeutic benefit)9.

The overall process of clinical trials generally takes 6-9 years, with each phase requiring successful completion with rigorous standards before a vaccine candidate advances to the next stage (Figure 1).

Following clinical trials, the company must submit a biological license application (BLA) to the FDA with all the data from preclinical and clinical trials, information about the manufacturing facility the vaccine was made in, and information about dosage9. The process for reviewing and approving the BLA typically takes 1-2 years (Figure 1). Finally, upon approval, the vaccine can be manufactured and distributed to the public.

The COVID-19 Vaccine: How We Made It So Well, So Fast

Due to the typical vaccine development timeline lasting an average of 6-12 years, a degree of understandable skepticism arose surrounding the COVID-19 vaccine, which took less than a year to put out into the market. How could we get it done so fast and still have it be safe?

Development of the COVID-19 vaccines was dramatically accelerated because in global health emergencies, the government unites pharmaceutical companies, academic institutions, nonprofit organizations, government agencies, and other international counterparts10. This unification towards a common purpose was performed on a global scale, the likes of which the world had never seen. Clinical trials were still rigorous and involved thousands of people10 but accelerated due to the severity of the pandemic. All three regular phases of clinical trials were still done (Figure 1), but certain steps were combined (such as testing for safety and immune responses) in the interest of saving time (and lives)11. After clinical trials, the FDA did their evaluations and utilized an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) to authorize the vaccines to be distributed quickly10.

Of course, none of this would have been possible if the groundwork for using mRNA – the biotechnological basis for the COVID-19 vaccines – hadn’t been established in 1995 by Dr. Katalin Karikó and Dr. Drew Weissman, and developed by many over the subsequent decades. The team won the 2023 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine for their pioneering work.

Although the COVID-19 vaccine development did not follow the traditional timeline, key safety and efficacy steps remained intact. After distribution, the world saw a decline in COVID-19 cases and emergency visits12, a true testament to the importance of the vaccine as well as scientific collaboration in responding to a public health crisis.

Exploring innovative vaccine delivery methods

How can researchers improve delivery of vaccines? One groundbreaking idea is using mosquitoes to deliver vaccines to humans. Mosquitoes are one of the deadliest animals on Earth due to their ability to infect people with diseases like malaria, dengue, and Zika. These mosquito-borne illnesses infect millions of people every year and lack effective vaccines and treatment. Moreover, these diseases are becoming an increasing global health threat due to the Earth’s rising temperature, creating climates more favorable for mosquitos.

How mosquitoes spread disease

Mosquitoes become carriers for disease by ingesting blood of a person who is infected with a pathogen. Once ingested, the pathogen moves to the mosquito’s midgut where it can multiply for 10-14 days before crossing into the mosquito’s bloodstream6, and then to the salivary glands. Once in the salivary glands, the mosquito can spread the pathogen into another person6. A well-studied example of this process is malaria, a life-threatening mosquito-borne disease caused by Plasmodium parasites3 (Figure 2).

Malaria occurs when an infected mosquito injects a Plasmodium parasite called sporozoites into the blood stream while it is feeding. In people, malaria can wreak havoc on the liver and blood, leading to symptoms like anemia and jaundice4. Without treatment, a patient faces more severe complications, such as coma, organ failure, and death. Although there are anti-malarial treatments, many heavily affected countries face serious challenges distributing these treatments. Therefore, designing mosquitos to administer the vaccine would overcome a main obstacle of eradicating malaria and has the potential to revolutionize vaccination methods and reduce disease transmission 7. If a vaccine works and makes it through the rest of the rigorous development process and safety trials, we could live in a world where mosquitoes could spread immunity rather than illness!

How mosquitos could spread vaccines

The setup:

In a recent study, a team of researchers at the University of Washington aimed to utilize genetically modified sporozoites, delivered by mosquitoes, that were capable of eliciting an immune response to safely protect against malaria4. Genetic modification is a common research technique that was utilized to alter DNA, in this case allowing for a safer vaccine.

DNA has numerous genes, which serve as instruction manuals for cells to carry out the intricate processes that keep cells – and by extension, whole organisms – alive. The scientists altered three sporozoites genes to weaken the pathogen so the parasite cannot cause disease. The weakened sporozoites trigger an immune response that helps the body know its enemy, so if ever faced with a real malaria infection, the immune system will already remember, respond, and protect against malaria.

The trial:

After extensive pre-clinical research, a 12-month clinical trial was conducted to test the efficacy of delivering the malaria vaccine via mosquito bites (Figure 3)4. In the trial, eligible participants were given ~200 bites on their arms from mosquitoes with the modified malaria parasite, every month for 4-6 months. Later, patient blood samples were analyzed to confirm that the genetically modified sporozoites transferred by the mosquito bites would never be able to give the volunteers malaria, due to the scientists’ modifications.

Analysis from the participants’ blood revealed a sufficient immune response that produced antibodies to protect against malaria. A month after the last immunization was given, the participants were introduced to malaria in a controlled manner, in which each participant was bitten five times by mosquitoes infected with un-modified (capable of causing disease) Plasmodium sporozoites to induce a potential malaria infection. The participants were monitored for symptoms for a month after infection, and researchers found that 50% of the participants tested negative for malaria. Those participants that were positive for malaria were given an antimalarial drug to clear their infections.

Results assessment, safety checkpoints in action:

The study showed that this vaccine strategy can generate an immune response, is safe, and provides protection against a controlled malaria infection. However, there are several drawbacks that the researchers themselves pointed out in their study.

The delivery of this vaccine is through a mosquito bite and would require vaccine-carrying mosquitoes to be released into the wild; as such, scientists would have no way to control the number of bites they give, and to whom. Also, since we cannot control mosquitoes in the wild, if this vaccine strategy were to be implemented, people could receive vaccinations without consent. Also – in the study, patients required ~200 mosquito bites for each immunization; this in and of itself could cause adverse side effects. No one likes being bitten by mosquitoes, especially hundreds of them!

Because of these concerns, the researchers decided to shift from a mosquito-delivered vaccine strategy towards instead using the genetically modified sporozoites in a traditional injectable vaccine, a delivery method that allows for precise dosage and consistency. This study highlights the rigorous nature of vaccine development process and how scientists will continuously adapt their approach to create the best, safest vaccine.

So: could we ever see vaccination-via-mosquito?

The answer is: maybe!

Interestingly, other researchers are looking into creating mosquito-delivered vaccines5,8. In time, we may be able to overcome dosing and safety challenges. While this concept is still in its early stages, these studies highlight its potential. Although the concept of vaccination-via-mosquito seems futuristic, imagine a world where a single mosquito bite could provide you with full protection from a mosquito-borne disease. The work of all these researchers – and the rigor of our vaccine development process – lays the foundation for such possibilities.

TL; DR

- Vaccines undergo rigorous development to ensure safety and efficacy

- A recent study created a malaria vaccine using a non-pathogenic parasite delivered to humans by mosquitoes

- Scientists discontinued using the mosquito-delivered vaccine to focus instead on an injectable vaccine format

Reference

- Weng, S.-C., Masri, R. A. & Akbari, O. S. Advances and challenges in synthetic biology for mosquito control. Trends Parasitol. 40, 75–88 (2024).

- Yen, P.-S. & Failloux, A.-B. A Review: Wolbachia-Based Population Replacement for Mosquito Control Shares Common Points with Genetically Modified Control Approaches. Pathogens 9, 404 (2020).

- Crutcher, J. M. & Hoffman, S. L. Malaria. in Medical Microbiology (ed. Baron, S.) (University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, Galveston (TX), 1996).

- Murphy, S. C. et al. A genetically-engineered Plasmodium falciparum parasite vaccine provides protection from controlled human malaria infection. Sci. Transl. Med. 14, eabn9709 (2022).

- Wen, D. et al. Suppression of flavivirus transmission from animal hosts to mosquitoes with a mosquito-delivered vaccine. Nat. Commun. 13, 7780 (2022).

- Mueller AK, Kohlhepp F, Hammerschmidt C, Michel K. Invasion of mosquito salivary glands by malaria parasites: prerequisites and defense strategies. Int J Parasitol. 2010 Sep;40(11):1229-35. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2010.05.005. Epub 2010 Jun 8. PMID: 20621627; PMCID: PMC2916662.

- Chuma J, Okungu V, Molyneux C. Barriers to prompt and effective malaria treatment among the poorest population in Kenya. Malar J. 2010 May 27;9:144. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-144. PMID: 20507555; PMCID: PMC2892503.

- Lamers OAC, Franke-Fayard BMD, Koopman JPR, Roozen GVT, Janse JJ, Chevalley-Maurel SC, Geurten FJA, de Bes-Roeleveld HM, Iliopoulou E, Colstrup E, Wessels E, van Gemert GJ, van de Vegte-Bolmer M, Graumans W, Stoter TR, Mordmüller BG, Houlder EL, Bousema T, Murugan R, McCall MBB, Janse CJ, Roestenberg M. Safety and Efficacy of Immunization with a Late-Liver-Stage Attenuated Malaria Parasite. N Engl J Med. 2024 Nov 21;391(20):1913-1923. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2313892. PMID: 39565990.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). How vaccines are developed and approved for use. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/basics/how-developed-approved.html

- Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. (n.d.). Emergency use authorization for vaccines explained. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/vaccines/emergency-use-authorization-vaccines-explained

- Vaccine research & development. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. (n.d.). https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/vaccines/timeline

- Christie A, Henley SJ, Mattocks L, et al. Decreases in COVID-19 Cases, Emergency Department Visits, Hospital Admissions, and Deaths Among Older Adults Following the Introduction of COVID-19 Vaccine — United States, September 6, 2020–May 1, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:858–864. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7023e2