By: Alexandra Evans

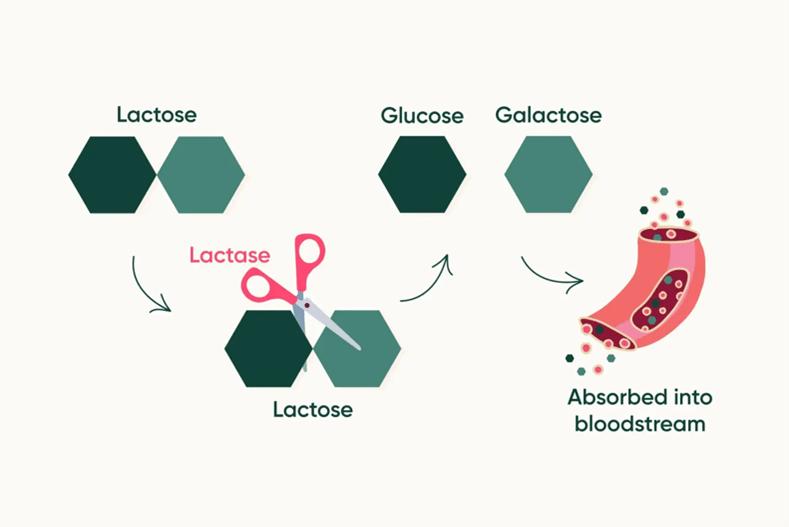

As children, we are told to drink milk to develop strong bones. However, approximately 70% of the global population are lactose intolerant, which means they lack the ability to digest lactose in milk-containing dairy products.1 Lactose is the predominant carbohydrate, or sugar, found in milk, as well as its main energy source. Upon digestion, lactose is broken down by b-galactosidase, an enzyme more commonly known as lactase, which is exclusively made in the small intestine.3 Lactase breaks down lactose into its component sugars, glucose and galactose, which are absorbed into the intestine and bloodstream, circulated throughout the body, and used for energy (Figure 1). The inability of individuals with lactose intolerance to digest and absorb lactose leads to a myriad of gastrointestinal complications such as increased gas, bloating, stomach pain, and diarrhea.

In most individuals, lactase activity peaks at birth and steadily decreases into adolescence.4 By adulthood, diminished lactase activity results in an inability to properly digest lactose. However, approximately 30% of adults maintain enough lactase activity levels to digest lactose, a phenomenon known as lactase persistence (LP).4,5,6 Rates of LP vary between and within countries and traditionally have been higher in regions such as Scandinavian Europe and the Middle East due to increased rates of dairy cattle domestication. LP is believed to have emerged as an outcome of positive selection – the evolutionary process in which physical characteristics that grant a survival advantage are passed down throughout generations – because such cultures have had a consistent ability to consume dairy. Due to this positive selection, LP has a strong genetic basis.

Genetic Mechanisms Underlying Lactose Persistence

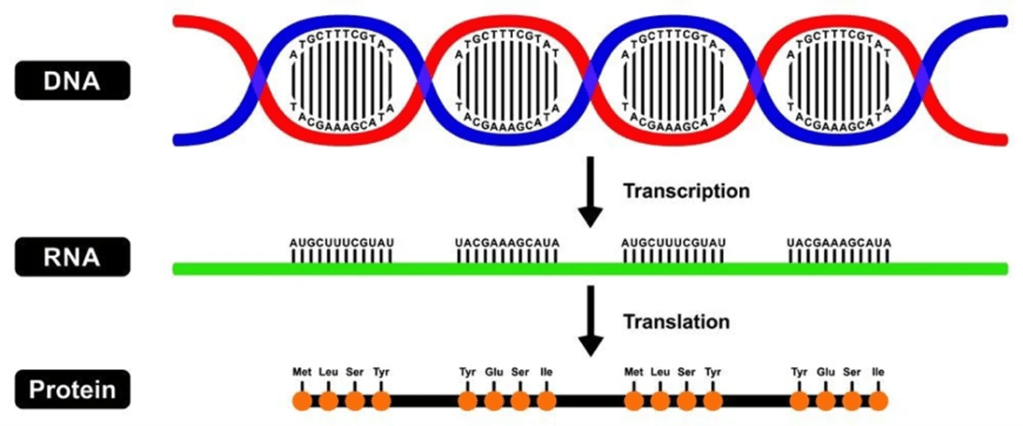

Before diving into the genetics behind LP, it is important to revisit the central dogma of biology (Figure 2). The central dogma explains how genetic information is used to make proteins. First, DNA, which is made up of individual molecules called nucleotides, is copied into RNA through a process called transcription. Then, RNA is used to make proteins during translation. This process is illustrated by the lactase-producing gene LCT, which provides molecular instructions for making the lactase protein.7 However, sometimes there are changes in the nucleotide sequence of DNA that have downstream effects on the proteins that are made.

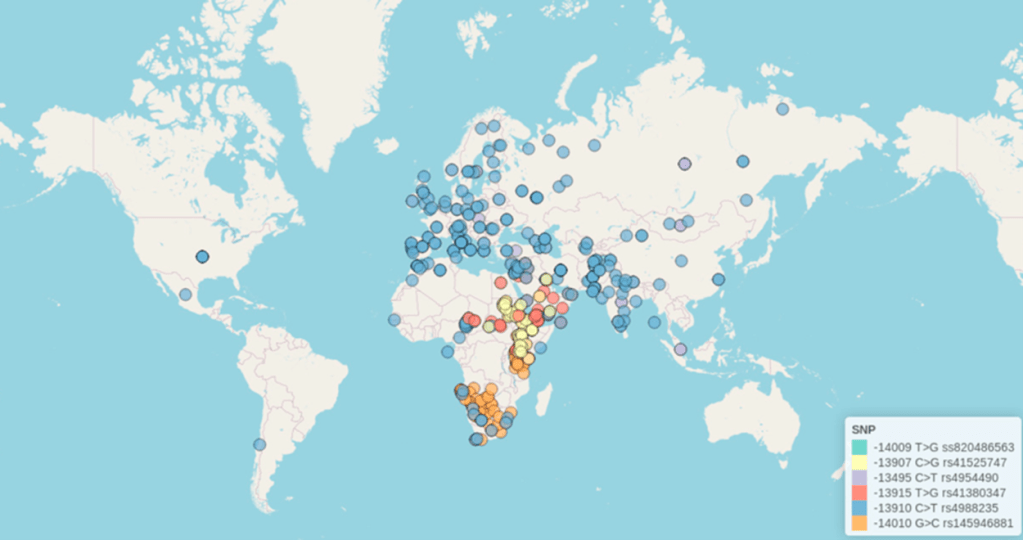

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) describe specific changes, or mutations, in the DNA sequence. SNPs occur when one of the four nucleotide bases in a DNA sequence is changed to another base. As of 2024, up to 23 different SNPs in the LCT gene have been documented in specific cultural populations across the globe, indicating that there are significant genetic mechanisms underlying the ability to digest lactose (Figure 3).1

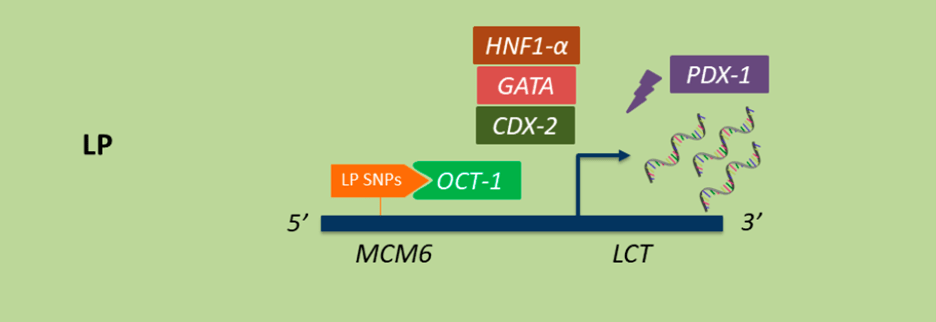

Research shows that depending on where SNPs occur within the LCT gene, the expression, or production of lactase changes drastically. This includes LP, which is caused when there are SNPs close to LCT. Different combinations of these SNPs increase LCT expression by creating more favorable binding sites for transcription factors.1,8 Transcription factors are proteins that bind to specific regions of a DNA sequence to make sure gene expression is turned on or off at the appropriate time. Some transcription factors that alter LCT expression include OCT-1, HNF1-a, GATA, and CDX-1 (Figure 4). When specific SNPs are present, transcription factors, including OCT-1 shown below, bind more readily to the area of DNA that regulates LCT, MCM6, increasing LCT expression. 7,9

Higher LCT expression leads to increased intestinal lactase production and enzyme activity levels. Traditionally, lactase enzyme activity is elevated during infancy when milk is the primary food source. Milk becomes less vital as a food source as we age and as a result, lactase enzyme activity significantly decreases.1 Those who are lactase persistent maintain high levels of LCT expression and lactase activity throughout their lives, allowing them to continue digesting lactose without any issues well into adulthood.

Genetic Mechanisms Underlying Lactose Intolerance

On the other hand, individuals with lactose intolerance possess lower lactase enzyme activity levels due to decreased lactase gene expression.2 There are several conditions that fall under the lactose intolerance umbrella, including congenital lactase deficiency, secondary hypolactasia, and lactase non-persistence, each with its own unique genetic explanation.1 Mutations in the LCT gene lead to the development of congenital lactase deficiency, which appears at the onset of nursing and is rare, affecting less than 10% of the neonatal population.2 Infants with this condition cannot consume breast milk nor dairy-based formula, meaning they must consume dairy-free formula for their primary food source. On the other hand, secondary hypolactasia is not genetic in nature and is instead caused by physical damage to intestinal lactase and can occur at any point in life. Like individuals with congenital lactase deficiency, those with secondary hypolactasia do not possess lactase and therefore cannot digest lactose-containing dairy products.

The large majority of individuals who cannot digest lactose are deemed as lactase non-persistent (LNP), meaning they lose the ability to process lactose during childhood.4,5,6 LNP is what we normally think of as lactose intolerance. As with LP, genetics play a pivotal role in the onset of LNP, but different genetic factors become crucial players in the underlying mechanism. In LNP, there are no SNPs present to promote the binding of transcription factors to DNA. Instead, a different protein called a repressor binds to the DNA and directly reduces LCT expression, leading to decreased lactase activity levels.10 Essentially, this information suggests the downregulation of LCT is due to a mutation in the LCT gene itself. However, mechanisms besides mutations may also be at play in downregulating LCT expression. Studies have found that production of the LCT gene is also regulated through a process called methylation, where a methyl group consisting of one carbon atom and three hydrogen atoms is added to DNA. In this case, methylation prevents transcription factors from binding to DNA, which leads to a decrease in LCT expression.11

Despite the differences in the onset of congenital lactase deficiency, secondary hypolactasia, and LNP, the symptoms remain the same as these individuals experience similar gastrointestinal distress. Beyond the genetic mechanisms underlying lactose intolerance, it is also crucial to explore how LNP is identified and leads to a lactose intolerance diagnosis.

How is Lactose Intolerance Diagnosed?

Most of the time, lactose intolerance is self-diagnosable as most people tend to notice gastrointestinal distress such as stomach pain and diarrhea within 30 minutes to 2 hours following dairy consumption. However, it is possible to confirm lactose intolerance with a formal diagnosis through various forms of testing. The most accurate assessment is a lactase activity assay, which measures lactase levels from a small sample of tissue obtained from an intestinal biopsy.1,2 Unfortunately, this procedure is invasive and not always practical. Other testing options include bloodwork or a hydrogen breath test.1,12 The former test measures blood glucose following lactose consumption while the latter measures the amount of hydrogen in your breath after lactose consumption. Decreased blood glucose and increased hydrogen in your breath after eating lactose can indicate lactose intolerance. Fortunately, lactose intolerance is a condition that can be treated with dietary changes.

What is the Best Course of Treatment?

The most obvious course of action would be to avoid lactose altogether or implement a low-lactose diet. With the rise in popularity of vegan diets, lactose- and dairy-free alternatives have become more widely available to consumers. One option could be opting for lactose-free dairy products. These products do not contain lactose but are still derived from cow’s milk. One example is Fairlife® milk. To remove lactose, Fairlife® milk is ultra-processed, after which lactase is added back into the milk as a precautionary measure to break down any residual lactose. Another example is the lactose-free yogurts offered by Chobani®, which undergo a similar process where they are fermented and strained to decrease lactose levels to negligible amounts. Like the Fairlife® milk, some of these yogurts also contain lactase to help digest any remaining lactose.

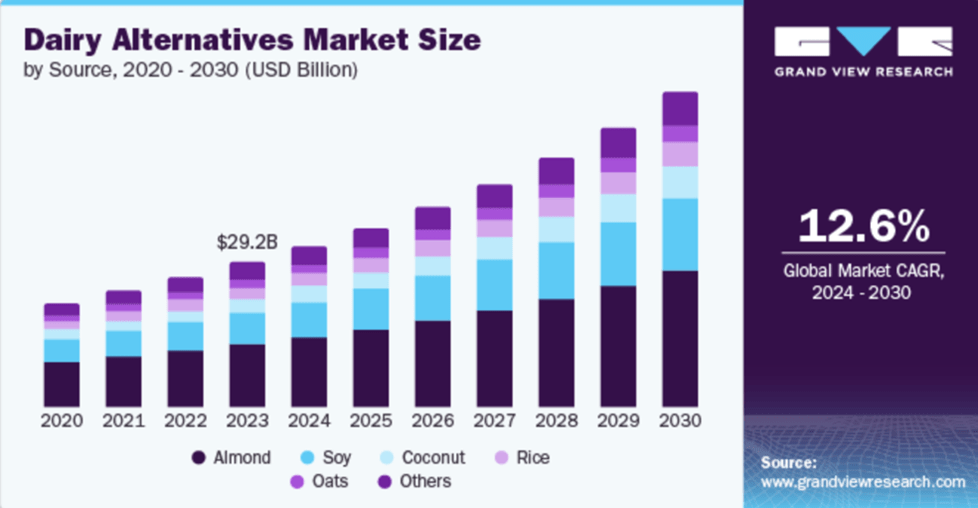

Other popular options for the lactose intolerant community include dairy-free, plant-based products. Dairy lovers and aficionados may also choose from a variety of plant/nut-based milks such as oat, almond, coconut, walnut, cashew, and macadamia that can be found in dairy-free cheeses, yogurts, milks, creams, and butters alike. However, one caveat is trying to find new lactose- or dairy-free products that taste delicious and provide similar nutritional value as some traditional lactose-containing dairy products. Fortunately, increased awareness surrounding special dietary needs has caused the consumer demand for lactose- and dairy-free products to skyrocket, and the global dairy alternative market is expected to increase by approximately 12.6% over the next few years (Figure 5). This means that you will not have to sacrifice your love of dairy products if you are lactose intolerant!

Lactose intolerance is a common condition that results as a combination of biology, genetics, and culture. While the inability to digest lactose leads to gastrointestinal distress, a growing understanding of the underlying genetic basis of the condition as well as advancements in food science have allowed for the increased development of effective dietary solutions. Today, there is an abundance of lactose-free and plant-based alternatives that make it possible for you to indulge in your favorite dairy treat.

TL;DR

- Lactose intolerance is caused by a genetically programmed reduction in lactase

- Mutations in the LCT gene increase lactase levels, promoting lactose digestion

- Lactose-free or plant-based products provide alternative options

Reference

- Anguita-Ruiz, A., Aguilera, C. M., & Gil, Á. (2020). Genetics of lactose intolerance: An updated review and Online Interactive World Maps of phenotype and genotype frequencies. Nutrients, 12(9), 2689. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12092689

- Forsgård, R. A. (2019). Lactose digestion in humans: Intestinal lactase appears to be constitutive whereas the colonic microbiome is adaptable. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 110(2), 273–279. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqz104

- Montgomery, R. K., Krasinski, S. D., Hirschhorn, J. N., & Grand, R. J. (2007). Lactose and lactase—who is lactose intolerant and why? Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 45(S2). https://doi.org/10.1097/mpg.0b013e31812e68f6

- Swallow, D. M. (2003). Genetics of lactase persistence and lactose intolerance. Annual Review of Genetics, 37(1), 197–219. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.genet.37.110801.143820

- Rossi, M., Maiuri, L., Fusco, M., Salvati, V., Fuccio, A., Auricchio, S., Mantei, N., Zecca, L., Gloor, S., & Semenza, G. (1997). Lactase persistence versus decline in human adults: Multifactorial events are involved in down-regulation after weaning. Gastroenterology, 112(5), 1506–1514. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70031-3

- Lee, M.-F., & Krasinski, S. D. (2009). Human adult-onset lactase decline: An update. Nutrition Reviews, 56(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.1998.tb01652.x

- Lewinsky, R. H., Jensen, T. G. K., Møller, J., Stensballe, A., Olsen, J., & Troelsen, J. T. (2005). T −13910 DNA variant associated with lactase persistence interacts with oct-1 and stimulates lactase promoter activity in vitro. Human Molecular Genetics, 14(24), 3945–3953. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddi418

- Liebert, A., López, S., Jones, B. L., Montalva, N., Gerbault, P., Lau, W., Thomas, M. G., Bradman, N., Maniatis, N., & Swallow, D. M. (2017). World-wide distributions of lactase persistence alleles and the complex effects of recombination and selection. Human Genetics, 136(11–12), 1445–1453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00439-017-1847-y

- Olds, L. C. (2003b). Lactase persistence DNA variant enhances lactase promoter activity in vitro: Functional role as a cis regulatory element. Human Molecular Genetics, 12(18), 2333–2340. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddg244

- Wang, Z., Fang, R., Olds, L. C., & Sibley, E. (2004). Transcriptional regulation of the lactase-phlorizin hydrolase promoter by PDX-1. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 287(3). https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpgi.00011.2004

- Labrie, V., Buske, O. J., Oh, E., Jeremian, R., Ptak, C., Gasiūnas, G., Maleckas, A., Petereit, R., Žvirbliene, A., Adamonis, K., Kriukienė, E., Koncevičius, K., Gordevičius, J., Nair, A., Zhang, A., Ebrahimi, S., Oh, G., Šikšnys, V., Kupčinskas, L., … Petronis, A. (2016). Lactase nonpersistence is directed by DNA-variation-dependent epigenetic aging. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, 23(6), 566–573. https://doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.3227

- Furnari, M., Bonfanti, D., Parodi, A., Franzè, J., Savarino, E., Bruzzone, L., Moscatelli, A., Di Mario, F., Dulbecco, P., & Savarino, V. (2013). A comparison between lactose breath test and Quick Test on duodenal biopsies for diagnosing lactase deficiency in patients with self-reported lactose intolerance. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, 47(2), 148–152. https://doi.org/10.1097/mcg.0b013e31824e9132