By: Elise M. Rizzi

Gently meandering around a gallery, shuffling between works of art and closely admiring the details. Such appreciation is a common experience, though few ponder, how did this art come to exist? Not who created this piece of art, but how this conglomeration of matter came together. How did each molecule, each atom, each electron, come to be in its current state? How have we exploited the chemical properties of matter to create substances that can come together to create a pleasing visual experience? The chemistry of art objects spans centuries across various artforms, ranging from ceramic pottery to various paints and all the way to the modern field of art conservation.

Ceramics

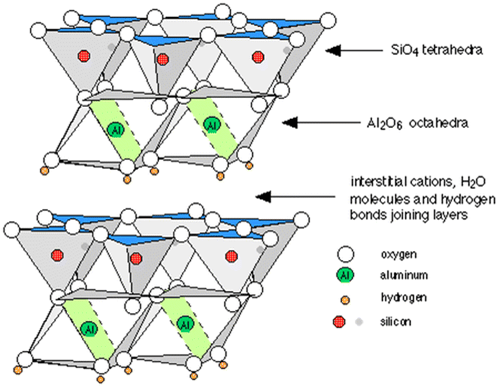

Ceramic pieces all start with clay, an aluminosilicate mineral made up of aluminum, silicon, and oxygen, with various degrees of moisture. The hydration status of the clay determines its texture and state: when aluminosilicate molecules are hydrated, the clay becomes malleable and can be manipulated into an infinite number of shapes.1 The atomic structure of clay is composed of sheets of silicon dioxide (SiO2) arranged in a triangular pyramid called a tetrahedron, and aluminum oxide (Al2O3) arranged in stacked pyramids that have square bases and triangular faces called an octahedron. These tetrahedra and octahedra are then arranged in sheets with positively charged ions held together by hydrogen bonds – a special type of attraction involving water molecules that is relatively weak and reversible (Figure 1).2 The color of the clay can depend on the cations present. For example, iron results in a reddish brown hue.1

At this stage, the pieces become “greenware” – a term exclusive to unfired pottery, referring to unripe or “green” fruit. Greenware pieces are often classified by their degree of moisture. Fresh pieces are classified as wet or damp. Pieces which have air dried a moderate amount are referred to as “leather-hard,” alluding to leather’s ability to maintain its shape despite its malleable properties. Finally, once a piece is air dried as much as possible and is ready to be fired in the kiln it is considered “bone-dry”.4

Firing refers to the process where the clay is permanently dehydrated through exposure to high temperatures in a special pottery oven called a kiln. Heat results in the formation of covalent bonds between ions of aluminum, silicon, and oxygen. Covalent bonds, unlike hydrogen bonds, are stronger links between two molecules and much more difficult to reverse. As dehydration occurs, water is produced and evaporates as a gas, replacing the weaker hydrogen bonds with stronger covalent bonds (see equation below), allowing the piece to hold its shape and gain strength.1

[clay]∙OH+HO∙[clay]→[clay]∙O∙[clay]+H_2 O(g)

After the initial firing to harden the piece, glazes and underglazes can be used to add color and/or sheen to the pieces followed by an additional one or two firings. A glass like covering is ideal for the glazed surface of a finished piece. Silica is often used for coating, which, when cooled quickly after melting, will form a solid with no crystalline structure called a “super-cooled liquid.” In this state, silica remains in its liquid form despite being at its solidifying temperature. Silica has an extremely high melting point of over 3100°F, which is too hot to be practical for routine use. Other compounds are added to the silica to lower its melting point, often combinations of metals and oxygen referred to as flux which can also alter the color and/or texture of the resulting glaze (Figure 2). However, flux often results in the glaze dripping off of the piece when heated, rather than spreading evenly over the piece. To help control the movement of the molten glaze, additives such as alumina, a flux with a high melting point, are used to add structure to the glaze and allow it to better adhere to the piece and prevent significant spread.5

Paints and Pigments

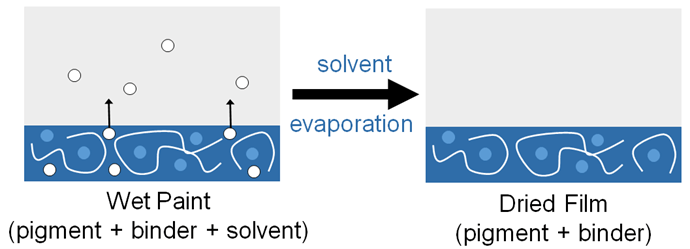

Paints are typically composed of an insoluble pigment to provide color, a binder to hold together the specks of pigment, and sometimes a vehicle to change the consistency for application (Figure 3). Different types of paints have different types and combinations of these three elements, allowing for various hues, textures, and permanency. For example, watercolor paints contain all three in which the pigment is combined with a binder and then added to water (the vehicle) to thin it out. For watercolors, gum Arabic is often used as the binder as it is unique in preventing seepage into paper whilst still being water soluble. Gum Arabic allows the particles of pigment to bind to both each other and the paper at the same time. As per its namesake, water is used as the vehicle, allowing for dispersion of the pigment and binder across the paper. Water then evaporates and leaves the pigment and binder on the page. Oil paints, in contrast, utilize a drying oil such as linseed oil as a binder. The vehicle in oil paints cannot be water due to the insolubility of oil in water; instead, mineral spirits or turpentine, which are more hydrophobic, are utilized. Like in watercolors, a dehydration reaction occurs as the solvent is evaporated; however, unlike watercolor paint the oil binder undergoes a more permanent polymerization reaction which suspends the pigment particles between layers.1 Different paint types can have different visual impacts. Artists may choose a given medium not only for ease of use or accessibility, but as a part of the art itself. For example, a delicate and dainty piece may be better suited in light watercolor, and a dark, heavy piece may give its best impact in a heavier oil paint.

Conservation

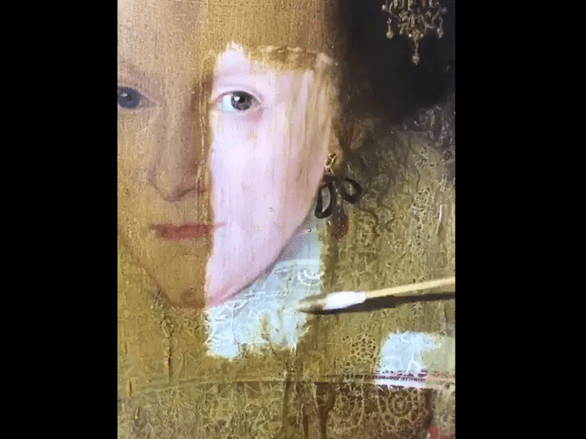

The science of art conservation is a relatively new field, focused on the restoration of historical pieces of art and their ongoing preservation. The restoration process varies greatly depending on the type of artform being restored. Typically, the first step involves intensive cleaning of the piece of art to remove dirt, oils, and aged/discolored varnish that have changed the artwork from its original form (Figure 4). This process delicately rubs solvents of various polarity on swabs over the surface of the piece of art to remove layers of dirt and grime sitting on top of the art. Polarity describes the degree to which a molecule holds a positive and/or negative charge. In this case, the degree of charge is important as different liquids can dissolve different types of solids. Just in the same way that some messes can be cleaned up with water, while others need alcohol. Different methods of identification such as microscopy and x-rays are often used to determine the contents of each layer of a piece of art to determine the best method of preservation for the given piece.8

From a preservation perspective, the focus is on protecting the piece of art from the things that allow for deterioration. Depending on the type of art this may look like utilization of different types of lighting or the use of frames/boxes that block certain types of light known to degrade art. Temperature and moisture control are also critical to the process of preservation (think about how quickly a wet piece of paper falls apart!), and of course minimizing exposure to human contact which can transfer oils and dirt to the surface of the art and rub off pigments. Hence, the gallery attendants hovering over you telling you to “step back,” may actually play more of a role in the chemical conservation of art than you may have thought.

TL;DR

- Clay transforms to solid pieces of pottery through irreversible dehydration

- Paints are formulations of insoluble pigments, binders, and evaporable solvents

- Conservation science allows for both restoration and preservation of art

Reference

- The Chemistry of Art. https://chemart.rice.edu/ (accessed 2024-10-28).

- June 2012, S. B. The chemistry of pottery. RSC Education. https://edu.rsc.org/feature/the-chemistry-of-pottery/2020245.article (accessed 2024-10-28).

- Aboudi Mana, S. C.; Hanafiah, M. M.; Chowdhury, A. J. K. Environmental Characteristics of Clay and Clay-Based Minerals. Geol. Ecol. Landsc. 2017, 1 (3), 155–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/24749508.2017.1361128.

- What is Greenware?. Seattle Pottery Supply. https://seattlepotterysupply.com/pages/what-is-greenware (accessed 2024-10-28).

- Glaze Chemistry Primer | Glaze Basics for Novice Potters by Hamilton Williams. Hamilton Williams Gallery. https://hamiltonwilliams.com/pages/glaze-chemistry (accessed 2024-10-28).

- Ceramic Materials Workshop – Understanding Glazes Class. Old Forge Creations. https://www.oldforgecreations.co.uk/blog/ceramic-materials-workshop-understanding-glazes-class (accessed 2024-10-28).

- Paint. https://chembam.com/resources-for-students/the-chemistry-of/paint/ (accessed 2024-10-28).

- Conservation Science. The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. https://www.mfah.org/research/conservation/conservation-science (accessed 2024-10-28).

- Ma, A. Watch 200 years of varnish get wiped off an oil painting in seconds. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/philip-mould-wipes-200-years-of-varnish-off-oil-painting-in-seconds-2017-11 (accessed 2024-10-28).