By: Natale Hall

The overlooked safety (or lack thereof) of menstrual products

Menstruation, or the process by which the inner lining of the uterus is shed each month, is experienced by roughly 1.9 billion individuals worldwide. However, the safety concerns of common menstrual products such as tampons has been largely overlooked despite nearly 100 years of use1. It is estimated that 70% of menstruating individuals in the United States use tampons as their choice of menstrual product instead of alternative options like pads or menstrual cups2. Since an average menstrual cycle requires about 20 tampons, and menstruation lasts for around 40 years, a menstruator could use up to 10,000 tampons over the course of their lifetime2. Despite these staggering numbers and tampons’ widespread use, there has been shockingly little research done investigating the overall safety of tampons and other menstrual products.

The results of a recent study identifying the presence of 16 heavy metals in tampons raise serious concerns about safety and potential risks to reproductive health3. This study, conducted by researchers at UC Berkely, sheds light on a critical public health concern that has long been ignored, and opens the door for deeper conversations on reproductive health and menstrual product safety.

Evaluating the presence of 16 heavy metals in tampons

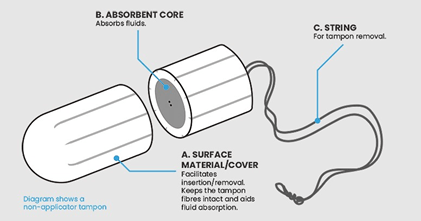

The study3 analyzed 60 samples obtained from 30 individual tampons across 24 different brands, with each sample containing portions of the absorbent core and outer covering shown illustrated in Figure 1 below.

The 16 heavy metals analyzed in the study were arsenic, barium, calcium, cadmium, cobalt, chromium, copper, iron, mercury, manganese, nickel, lead, selenium, strontium, vanadium, and zinc. To measure the concentration of non-mercury metals in the samples, a technique called mass spectrometry – or mass spec. as the cool kids (scientists) call it – was utilized.

Mass spectrometry is an analytical method in which molecules are identified and quantified based on their mass-to-charge ratios, or the amount of matter in a molecule relative to its electric charge4. To identify compounds with mass spec, first, a blank sample that does not contain any tampon components was measured to identify a background – what the machine detects when there is no sample present. This blank measurement was then used to calculate a method detection limit (MDL), which is the minimum concentration of a compound that can be accurately reported. This process is depicted in Figure 2.

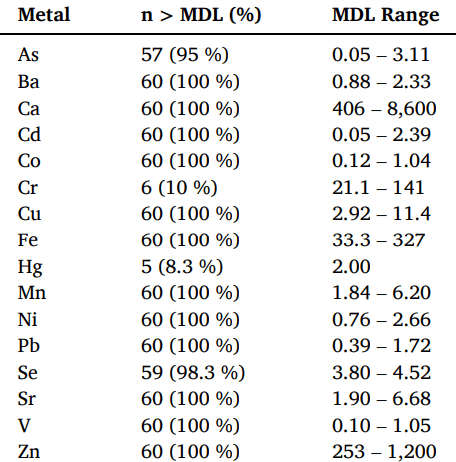

All 16 heavy metals were detected at concentrations above the MDL, detailed in Table 1. The most prevalent heavy metals were barium, calcium, cadmium, cobalt, copper, iron, manganese, nickel, lead, strontium, vanadium, and zinc, which were found in levels above the MDL in all 60 samples. Despite surpassing the MDL, most of these metals were found at concentrations within OSHA’s safe exposure limits, which are set based on dose-response studies that determine the lowest harmful dose of a substance. However, it is important to note that these exposure levels are not specific to vaginal absorption. Additionally, five of the metals identified in the tampons examined are considered toxic, meaning they are not safe at any level of exposure. These toxic metals included arsenic, cadmium, chromium, lead, and vanadium, with lead found in the highest concentration.

While there was minimal variability in heavy metal concentrations within individual tampons, the study found a high amount of variability between different categories of tampons. For example, organic tampons had lower median concentrations of barium, cadmium, cobalt, lead, and zinc and higher median concentrations of arsenic, calcium, chromium, iron, manganese, strontium, and vanadium compared to non-organic tampons. Country of origin also played a role in the heavy metal composition, with tampons obtained from the EU/UK having lower concentrations of cadmium, cobalt, and lead than US tampons. An additional point of variability was the tampon brand, with store-brand tampons showing higher copper, nickel, and selenium concentrations but lower zinc concentrations than their name brand counterparts. Although variability based on origin, brand, or other characterizations should be investigated further, the overall conclusion of the study is that virtually all tampons contain heavy metals, raising significant health concerns for tampon users.

The heavy metals identified in tampons are likely present due to either environmental contamination, or addition during production for various applications3. Heavy metals present in the atmosphere, soil, wastewater, pesticides, or fertilizers can be absorbed by plants that provide common tampon-making materials like cotton and rayon. This is supported by the differences in heavy metal composition in organic versus non-organic tampons reported in the study. However, it is also possible that some of the metals are purposefully added in the manufacturing process. Calcium, cobalt, chromium, copper, nickel, and zinc are common antimicrobial agents, while iron and manganese are used for odor control in various products. Additionally, calcium, strontium, and zinc are known lubricants that may be added to aid in application of the tampon, and barium, cadmium, cobalt, iron, manganese, and zinc have been identified as metals that could be added for pigmentation. While these are documented uses for the various heavy metals in menstrual products, there is very little known about how these substances may be impacting reproductive health.

Potential for Vaginal Absorption

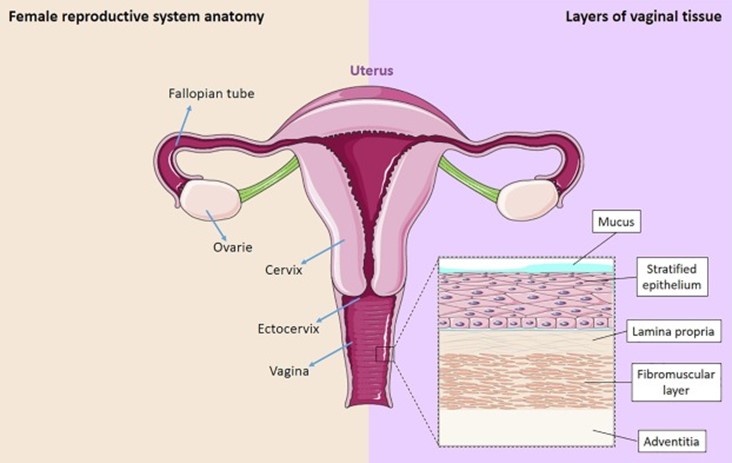

It is crucial to consider how heavy metals in tampons might be absorbed through the vaginal tissue, potentially impacting health and the reproductive system. The vaginal canal where the tampon is inserted is lined by the vaginal epithelium, a complex structure consisting of three layers5, illustrated in Figure 3.

The outermost layer is called the mucosa, which consists of epithelial cells that form a protective barrier, and the lamina propria that contains blood vessels. The epithelial cells are coated with a thick mucus that is produced from cells in the cervix. Drug administration studies have demonstrated that substances inserted into or applied on the vaginal canal are dissolved by the mucus and absorbed by the epithelium, where they travel down into the lamina propria and are taken up by the underlying blood vessels6. These studies show that vaginal administration of compounds are taken up by the vaginal epithelium and circulated throughout the entire body. However, research into whether vaginal epithelium absorbs chemicals from tampons is lacking. Thus, while no studies to date have demonstrated that heavy metals can enter the bloodstream through tampons, there is scientific basis for chemical absorption through the vagina. Currently, the FDA is conducting a follow-up investigation to better characterize the existence and extent of risks posed to menstruators by the heavy metals that have been detected in tampons.

Implications for Reproductive Health

The discovery of a variety of heavy metals in tampons underscores the need for continued research into the safety of menstrual products and the potential health risks associated with their use. While the study did not disclose specific brands, it was noted that many of the tampons used were top sellers obtained from several large chain retailers, suggesting that the results are applicable to widely used products and may impact millions. The presence of heavy metals in tampons not only calls into question the safety of this menstrual product, but of other menstrual products as well. Future studies investigating the possibility of vaginal absorption of heavy metals through tampons is critical and will provide menstruators with information they deserve as they navigate decades of menstrual cycles.

TL;DR

- There are millions of tampon users around the world

- A recent study detected 16 different heavy metals in tampons

- While the vagina can absorb drugs, it is unknown if heavy metals from tampons are entering the bloodstream

Reference

1. Americas, T. L. R. H.-. Menstrual health: a neglected public health problem. Lancet Reg. Health – Am. 15, (2022).

2. Period Poverty in the United States. Ballard Brief https://ballardbrief.byu.edu/issue-briefs/period-poverty-in-the-united-states.

3. Shearston, J. A. et al. Tampons as a source of exposure to metal(loid)s. Environ. Int. 190, 108849 (2024).

4. Garg, E. & Zubair, M. Mass Spectrometer. in StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL), 2024).

5. Balakrishnan, S. N., Yamang, H., Lorenz, M. C., Chew, S. Y. & Than, L. T. L. Role of Vaginal Mucosa, Host Immunity and Microbiota in Vulvovaginal Candidiasis. Pathogens 11, 618 (2022).

6. Srikrishna, S. & Cardozo, L. The vagina as a route for drug delivery: a review. Int. Urogynecology J. 24, 537–543 (2013).

7. dos Santos, A. M. et al. Recent advances in hydrogels as strategy for drug delivery intended to vaginal infections. Int. J. Pharm. 590, 119867 (2020).