By Luz E. Ortiz

Pregnancy is a season of hormonal, emotional and physical changes. I know because I have “been there and done that”! Despite being five years into my motherhood journey, it wasn’t until recently that I heard a passing comment by an older man mentioning how during pregnancy the baby’s cells travel to the mom to permanently become part of her. Now, this person is not from the scientific or medical communities, so I received this information with a grain of salt. Was this true? I was sure I would have heard about it from my physician, my genetics class or maybe social media, but that was not the case. So, I decided to do my own search, and here is what I found. Indeed, some of the baby’s cells remain inside the mother! Fetal cells do travel from the baby to the mother through the placenta, migrate through the mother’s body, and integrate into different tissues, causing a cellular “mixing” between the child and mother.

Microchimerism describes the presence in the body of a small population of foreign cells genetically distinct from the host1. The origin of the word stems from Greek mythology: the Chimera was a monster with the head of a lion, the body of a goat and the tail of a serpent – one creature with distinct parts. Although microchimerism occurs during organ transplantation, blood transfusion, and the development of identical twins2, pregnancy is the major source of natural microchimerism, and it occurs in every pregnancy!

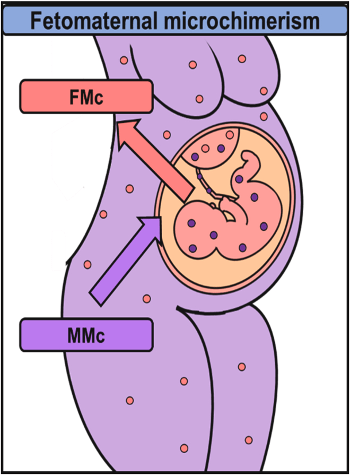

During pregnancy, a well-regulated exchange of molecules via the placenta occurs. For example, nutrients, oxygen, water and immunoglobulins are transferred from the mother to the child, and carbon dioxide and metabolic by-products are transferred from the child to the mother3. Moreover, cells are also exchanged between the baby and the mother, where the mother receives a larger number of fetal cells than the number of maternal cells received by the child3 (Figure 1).

This asymmetric transfer is believed to be a common mechanism by which fetal development is ensured. Fetal cells act as stem cells with the potential to mature into any cell lineage needed and contribute to the overall health of the mother2. Fetal microchimerism (FMc) defines the presence and persistence of fetal cells in the maternal blood and tissues during and after pregnancy.

FMc was first observed in 1893 by pathologist Georg Schmorl in Leipzig, Germany. Schmorl reported the finding of trophoblasts in the lungs of 17 deceased mothers with eclampsia, a rare but life-threatening pregnancy complication. Trophoblasts are a type of cell found in early fetal development that eventually differentiate, changing from their immature state into the placenta4,5. In addition to trophoblasts, a range of other cell types including monocytes, B cells, T cells, red blood cells, and hematopoietic pluripotent cells are found in the mother’s circulation after pregnancy6. In 1959, a study confirmed FMc by detecting fetal lymphocytes with the XY sex-chromosome signature in the circulation of pregnant women carrying male offsprings7. Later, development of accurate molecular techniques allowed the detection and amplification of fetal male DNA sequences in the blood and cells of pregnant women. Two of these new techniques included fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) assays and polymerase chain reaction (PCR), used for the visualization and amplification of a gene of interest in an individual’s cells. In 2014, a group from Cork, Ireland used FISH assays to assess whether fetal chimeric cells played a role in wound healing after pregnancy. Skin samples from unwounded skin areas of first-time moms undergoing cesarean section (C-section) and from C-section scars of women with previous C-sections were collected. A total of 70 women participated and were classified into 3 groups: no history of pregnancy loss, history of pregnancy loss and normal/uninjured skin. None of the women had a history of blood transfusion or organ transplant. FISH targeting the XY specific sequences identified cells with XY chromosomes in the skin cells from the C-section scars of women whose first child was male and delivered via C-section (Figure 2). On the contrary, skin samples from women who gave birth to a male child first via vaginal birth did not show chimeric skin cells. These data support the hypothesis that fetal chimeric cells aid in the mother’s wound healing. Also, they found male cells in women who gave birth to daughters but had experienced pregnancy loss of unknown fetal gender, confirming that fetal microchimerism occurs early in the pregnancy8.

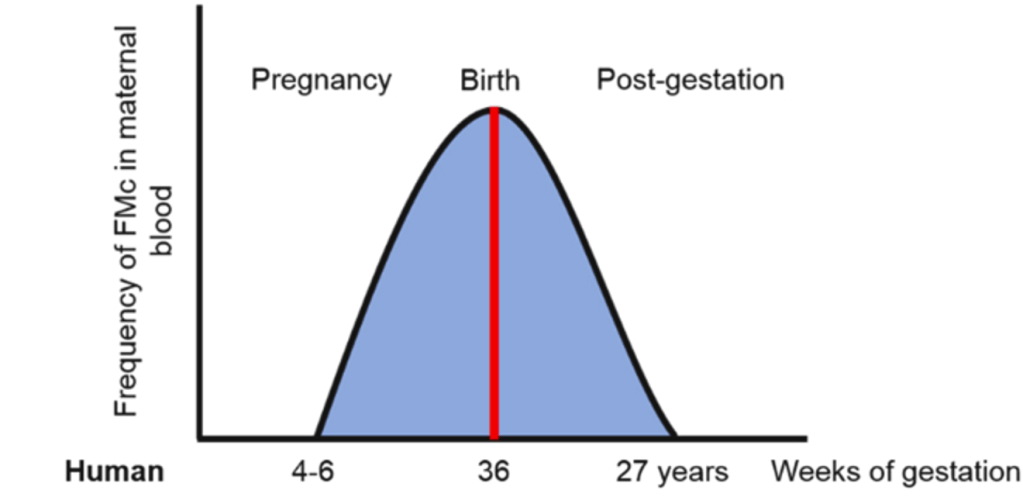

Fetal cell trafficking to the mother starts early during pregnancy, between week 4 and 6 of gestation, and it increases until weeks prior to birth (Figure 3). Microchimeric fetal cells have been reported to remain in the mother’s tissues for up to three decades following pregnancy! Though most fetal cells are cleared by the maternal immune system soon after delivery, a small group of fetal cells become chimeric and integrate into the mother’s organs, becoming part of the cell pool at their site of integration. Fetal cells have been detected in the mother’s lungs, liver, thyroid, kidneys, bone marrow, skin and heart! 6

Despite the natural occurrence of FMc, the effects of this phenomenon on the mother’s health are still not fully characterized. Some studies found that microchimeric fetal cells may have a beneficial effect for the mother by participating in the C-section wound healing process8, the suppression of lung tumor development and lowering the risk of breast, ovarian and bladder cancers!3,9,10 In contrast, other studies reported increased levels of microchimeric fetal cells in women with autoimmune diseases including systemic sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis, colon cancer and hepatitis C; supporting the detrimental effects of these cells in mothers. Furthermore, there are studies that proposed that FMc has no significant impact on the mother’s health11. Whether the effects of FMc are context-specific or influenced by external or internal factors, additional research needs to be conducted.

Either way, one thing is for sure, pregnancy changes a mother at all levels possible. The special bond that a mother shares with her child goes beyond the emotional connection; she truly always carries a piece of her child with her…in her cells.

TL; DR:

- During pregnancy, fetal cells enter the mother’s body, migrate to her organs and integrate into her tissues. This is called fetal microchimerism (FMc).

- FMc occurs in all pregnancies and has been reported since the late 1800s.

- The effects of FMc on the mother’s health are still divided. Studies have shown FMc has beneficial, detrimental or neutral impact on the health of the mother.

- Indeed, mothers carry a piece of their children with them…in their cells!

Reference

- Shrivastava S, Naik R, Suryawanshi H, et al. Microchimerism: A new concept. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2019;23(2):311, doi:10.4103/jomfp.JOMFP_85_17

- Dawe GS, Tan XW, Xiao ZC. Cell migration from baby to mother. Cell Adh Migr 2007;1(1):19-27

- Cómitre-Mariano B, Martínez-García M, García-Gálvez B, et al. Feto-maternal microchimerism: Memories from pregnancy. iScience 2022;25(1):103664, doi:10.1016/j.isci.2021.103664

- Lapaire O, Holzgreve W, Oosterwijk JC, et al. Georg Schmorl on trophoblasts in the maternal circulation. Placenta 2007;28(1):1-5, doi:10.1016/j.placenta.2006.02.004

- Fishel Bartal M, Sibai BM. Eclampsia in the 21st century. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2022;226(2S):S1237-S1253, doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2020.09.037

- Bianchi DW, Khosrotehrani K, Way SS, et al. Forever Connected: The Lifelong Biological Consequences of Fetomaternal and Maternofetal Microchimerism. Clin Chem 2021;67(2):351-362, doi:10.1093/clinchem/hvaa304

- Jacobs PA, Smith PG. Practical and theoretical implications of fetal-maternal lymphocyte transfer. Lancet 1969;2(7623):745, doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(69)90455-3

- Mahmood U, O’Donoghue K. Microchimeric fetal cells play a role in maternal wound healing after pregnancy. Chimerism 2014;5(2):40-52, doi:10.4161/chim.28746

- Hallum S, Jakobsen MA, Gerds TA, et al. Male origin microchimerism and ovarian cancer. Int J Epidemiol 2021;50(1):87-94, doi:10.1093/ije/dyaa019

- Gadi VK, Nelson JL. Fetal microchimerism in women with breast cancer. Cancer Res 2007;67(19):9035-8, doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4209

- Boddy AM, Fortunato A, Wilson Sayres M, et al. Fetal microchimerism and maternal health: a review and evolutionary analysis of cooperation and conflict beyond the womb. Bioessays 2015;37(10):1106-18, doi:10.1002/bies.201500059