By: Abbey Rebok

Cakes, cookies, pies – oh my! Desserts full of sugary goodness may be good for your soul, but it is no surprise that too much sugar may not be so sweet for your health. As of 2021, approximately 11.6% of the U.S. population has diabetes, and this number is expected to continue climbing. If current trends continue, it is estimated that one in three people born in the year 2000 will develop diabetes in their lifetime. Chronic overconsumption of sugar can result in obesity, which is a major risk factor for type 2 diabetes. The recommended daily amount of added sugar is 36 grams for men and 25 grams for women. To put this in perspective, a venti pumpkin chai latte from Starbucks contains a whopping 87 grams of sugar – more than 3 times the recommended daily limit for women and 2 times that for men. To combat overconsumption but still satisfy our sweet tooth, sugar substitutes have become a popular solution. Sugar substitutes, such as those marketed under the names Splenda and Sweet’N Low, satisfy sugar cravings seemingly without any repercussions – emphasizing the idiom of having one’s cake and eating it too – but are they too good to be true?

What are sugar substitutes?

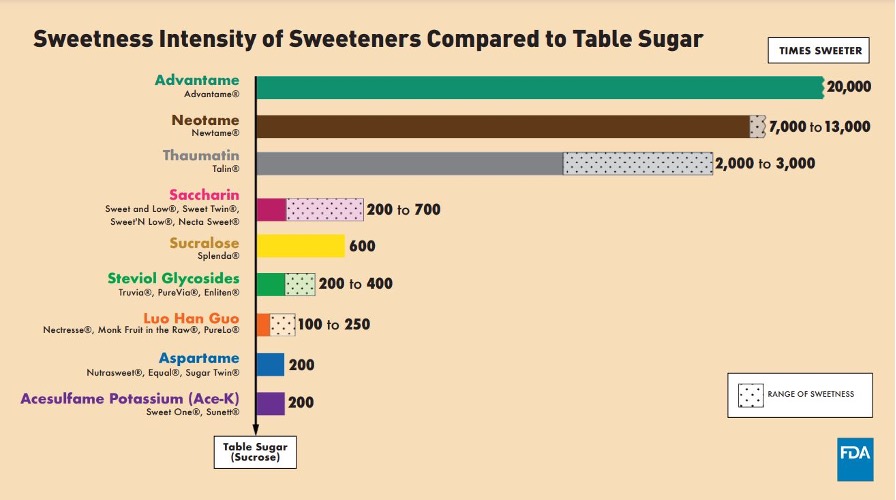

A variety of sugar substitutes exist and differ in their structure, origin, and number of calories. There are three main types of sugar substitutes: artificial sweeteners, sugar alcohols, and plant-derived sweeteners (also known as novel sweeteners). Artificial sweeteners are generally synthetic compounds that are remarkably sweeter than table sugar (Figure 1). Artificial sweeteners, such as aspartame, can have the same number of calories per gram compared to table sugar (4 calories/gram), but since very little is needed, their caloric contribution is negligible. Other artificial sweeteners, such as sucralose, are not readily metabolized and are excreted from the body intact, thus not providing any calories.

Sugar alcohols are derived from natural sugars, such as glucose or sucrose. Sugar alcohols can be naturally derived from certain fruits and vegetables, but most sugar alcohols used for commercial use are synthetically produced. While not as sweet as table sugar, sugar alcohols, such as xylitol, are known to supply texture to foods like chewing gum and hard candy. Sugar alcohols can contain up to 3 calories per gram, making them another low-calorie alternative like artificial sweeteners.

Plant-derived sweeteners, such as monk fruit sweeteners and stevia, are non-caloric sugars found from natural sources but are still sweeter than table sugar. While derived from a natural source, these sugar substitutes tend to be chemically processed to maintain purity and potency. Despite chemical processing, plant-derived sweeteners are typically less processed than artificial sweeteners and sugar alcohols. Japan began commercially producing high purity stevia extract in the 1970s, but stevia didn’t gain popularity in the U.S. until its safety approval by the FDA in 20081. In comparison, aspartame was approved by the FDA in 1974. Due to the recent introduction of plant-derived sweeteners in the food industry compared to other sugar substitutes, products containing plant-derived sweeteners may be less common.

Are sugar substitutes safe?

Some sugar substitutes, such as sugar alcohols, are labeled as “generally recognized as safe (GRAS)” by the FDA and do not require pre-market approval. Sugar substitutes that are not GRAS must undergo pre-market food additive approval prior to use. Therefore, sugar substitutes are generally regarded as safe for the general public. Despite approval by the FDA, some sugar substitutes may not be safe for certain individuals. For example, one of the metabolites of aspartame is phenylalanine, an amino acid that is normally broken down when levels are too high. However, individuals with phenylketonuria (PKU) are unable to break down excess phenylalanine, which may lead to intellectual disability and other neurological conditions. Thus, individuals with PKU should avoid aspartame to prevent adverse health effects.

With the rise of “diet” and “zero sugar” products, there is growing concern regarding the long-term health effects of sugar substitutes. A common concern regarding sugar substitutes is their effect on gut microbiota. A balanced gut microbiome is pivotal for proper digestion, nutrient production, and gut health, among other essential processes. Studies in mouse models suggest that certain sugar substitutes, such as sucralose, can lead to imbalances in gut microbiota (dysbiosis) by promoting the growth of Proteobacteria2. Proteobacteria are a group (phylum) of bacteria that typically comprise less than 5% of gut microbiota and have roles in maintaining an anaerobic environment and vitamin production. Increased Proteobacteria is linked to inflammation and diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer3. However, studies evaluating the effect of sucralose on gut microbiota in humans have reported conflicting results, with some studies reporting an effect while others observe no change in gut microbiota4.

In recent years, concerns emerged regarding several artificial sweeteners and their carcinogenic potential. A joint investigation by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and the Joint Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) concluded that aspartame was possibly carcinogenic but insufficient data in humans prevented it from being classified as such. The most striking research linking aspartame to cancer stemmed from work done by Drs. Morando Soffritti and Fiorella Belpoggi at the Ramazzine Institute which concluded that aspartame caused tumors in mice and rats. While initially ridiculed for their conclusions, reanalysis of their data confirmed their findings and thus warrants further investigation into the carcinogenic potential of aspartame in humans. In 1981, saccharin was designated as reasonably anticipated to be a human carcinogen based on rat studies that indicated saccharin at dietary concentrations greater than 1% resulted in bladder cancer. However, further evaluation revealed that the mechanism of carcinogenesis that occurred in rats was not applicable to humans, so saccharin was removed as a suspected carcinogen in 2000. While there is very minimal evidence in humans to suggest that sugar substitutes cause cancer, there remains a lack of studies evaluating if long-term use of these products increases the risk of cancer.

Initial evidence proposes that various sugar substitutes may increase the risk for cardiovascular disease. Xylitol and erythritol, both sugar alcohols, have been loosely linked to cardiovascular disease based on data that suggests both increase blood clotting which may increase the risk of heart attack and stroke. In line with this, increased xylitol and erythritol blood levels were found to be linked with future risk of cardiovascular events. Moreover, one study suggests that artificial sweeteners increase the risk of heart attacks by 9% and strokes by 18%. Despite these findings, there is insufficient data to definitively state that sugar substitutes increase cardiovascular disease risk.

While defined as safe by the FDA, there exists preliminary data that speculates some sugar substitutes may pose a health risk. Currently, there is limited data to warrant the removal of any sugar substitute from the market. However, further studies are required to determine if sugar substitutes may be harmful with long-term use. So next time you pick up a Coke Zero or sugar-free candy, take a peek at which sugar substitutes are in your sweet treat.

TL;DR

- Sugar overconsumption contributes to obesity and diabetes.

- Sugar substitutes are low- or non-caloric alternatives to added sugar.

- While considered safe by the FDA, changes in gut microbiota and increased risk of cancer and cardiovascular disease may be linked to sugar substitutes.

Reference

- Perrier, J. D., Mihalov, J. J., & Carlson, S. J. (2018). FDA regulatory approach to steviol glycosides. Food and chemical toxicology : an international journal published for the British Industrial Biological Research Association, 122, 132–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2018.09.062

- Rodriguez-Palacios, A., Harding, A., Menghini, P., Himmelman, C., Retuerto, M., Nickerson, K. P., Lam, M., Croniger, C. M., McLean, M. H., Durum, S. K., Pizarro, T. T., Ghannoum, M. A., Ilic, S., McDonald, C., & Cominelli, F. (2018). The Artificial Sweetener Splenda Promotes Gut Proteobacteria, Dysbiosis, and Myeloperoxidase Reactivity in Crohn’s Disease-Like Ileitis. Inflammatory bowel diseases, 24(5), 1005–1020. https://doi.org/10.1093/ibd/izy060

- Moreira de Gouveia, M. I., Bernalier-Donadille, A., & Jubelin, G. (2024). Enterobacteriaceae in the Human Gut: Dynamics and Ecological Roles in Health and Disease. Biology, 13(3), 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology13030142

- Conz, A., Salmona, M., & Diomede, L. (2023). Effect of Non-Nutritive Sweeteners on the Gut Microbiota. Nutrients, 15(8), 1869. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15081869