By: Rachel Kang

You may have noticed products at the grocery store proudly advertising “No MSG Added” on the packaging. We’ve been taught to avoid and fear MSG, but have you ever questioned why that is – or what MSG even is?

Monosodium glutamate (MSG) is a common additive to savory dishes that adds an extra umami, or savory,taste to food, used especially in Asian cuisines. Despite its popularity, this salt is infamous for allegedly causing headaches, burning sensations, and chest tightness. The negative reputation of MSG is so widespread that even some natives of East Asian countries have stopped using MSG. However, it turns out that the history behind the alleged symptoms is the result of a lot of bad (and racist!) science.

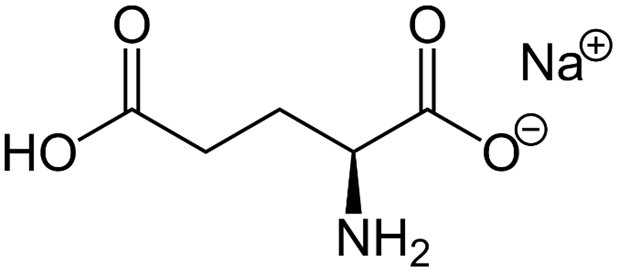

MSG is a sodium salt of glutamic acid (Figure 1) that’s made synthetically or found naturally in foods such as tomatoes and cheese. The salt was first isolated by Japanese biochemist Kikunae Ikeda who was attempting to identify the substance that caused the savory taste of kombu, a type of edible seaweed commonly used in Asian cooking. Ikeda noticed that kombu didn’t taste like any of the four main tastes (sweet, salty, sour, or bitter) but instead seemed to be defined by a fifth taste that had yet to be categorized. This fifth taste was later referred to as umami, which translates to “delicious, savory taste” in Japanese1,2.

As Asians began immigrating to the United States, many Americans grew to love MSG-containing East Asian dishes, especially Chinese American food. Quick-and-easy meals like TV dinners and soldiers’ MRE rations were seasoned with MSG without much controversy. When, then, did the public change its tune regarding MSG?

In 1968, two doctors made a bet. Dr. Bill Hanson, an internal medicine doctor, would often jest with Dr. Howard Steel, an orthopedic surgeon, that orthopedic surgeons were “too dumb” to publish in prestigious academic journals like the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM). Dr. Hanson even bet $10 that Dr. Steel couldn’t get published. The two doctors were good friends who had a weekly tradition of eating Chinese food over beers. It was during one of these weekly meals that inspiration struck Dr. Steel, and he wrote a letter to the NEJM stating that he experienced worrying symptoms after consuming Chinese food. He signed the letter under the pseudonym “Dr. Robert Ho Man Kwok,” a pun on the phrase “human crock of you-know-what.” Steel also attributed Dr. Kwok to a fictional medical institution, the National Biomedical Research Foundation of Silver Spring, Maryland, to emphasize that this letter was a joke.

The letter was published a few weeks later under the title “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome.”

In the letter, “Dr. Kwok” hypothesized that the symptoms (headache, heart palpitations, muscle spasms) were due to MSG and the high sodium content in the food. Responses from other researchers began pouring in, and the NEJM printed an additional ten responses to the letter from other doctors reporting similar anecdotes. While it did seem like some doctors were aware of the joke, many readers trusted this information from the prestigious journal. Newspapers amplified the findings, leading many people to experience the “nocebo effect” in which a negative expectation can cause an outcome to be worse than normal3. Because people expected these symptoms after eating Chinese food, the deleterious effects manifested.

A year later, Dr. Herbert H. Schaumburg published a questionable study in Science isolating MSG as the main culprit in Chinese restaurant syndrome4. The first experiment involved six volunteers who had previously suffered from Chinese restaurant syndrome to see if they would experience a similar attack after eating wonton soup, a dish rich in MSG (Figure 2). The researchers then isolated the seven ingredients of wonton soup and found that only MSG provoked a response. This experiment is flawed as 1) the sample size is far too small to ensure that the results were not random, 2) the volunteers are people who have already experienced Chinese restaurant syndrome, so they may be under the influence of the nocebo effect, and 3) the results were not compared to those of a negative control, or a group of subjects that did not receive any MSG. Negative controls are essential to determine if observed results in the experimental group are due to the variable being investigated, or by the experimental procedure itself.

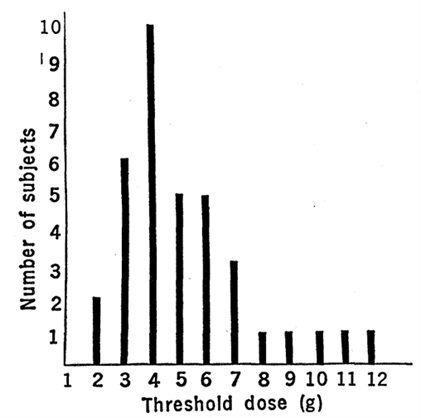

The study’s second experiment was an unblinded experiment. Blinding refers to the scientific process of concealing which group a particular individual is a part of. For instance, if this experiment was properly blinded, the volunteers would not have known if they were receiving MSG or some kind of control substance like salt. This way, the researchers would be able to assess if the effects were solely due to MSG or if participants’ expectations influenced the results. In this experiment, 36 volunteers received different doses of MSG to examine the threshold, or lowest dose, that would elicit the symptoms of Chinese restaurant syndrome (Figure 3). Researchers then monitored the volunteers for symptoms like burning sensations, chest tightness, or headache. The study concluded that the threshold dose ranged from 1.5-12 grams, with most of the volunteers experiencing symptoms at 3-4 grams of MSG. The administered doses were not corrected for volunteers’ height, weight, or sex, despite it being well documented that males and females require different doses of medicine, partly due to differences in body fat percentages5.

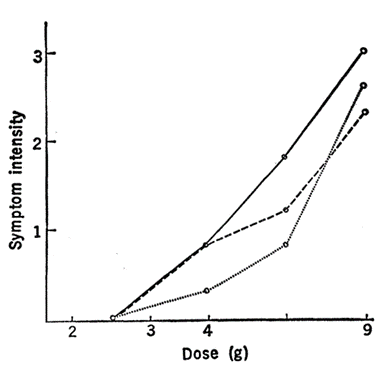

In the study’s third experiment, Schaumburg compared how different doses of MSG (2.5, 4, 6, and 9 g) affected symptom intensity(Figure 4). After receiving a dose of MSG, subjects rated their symptom intensity from 1-3, with 1 being “just perceptible” and 3 being “severe.” These results were obtained from six subjects who were not blinded to the experimental conditions. Once again, this experiment suffers from a small sample size and lack of experimental blinding, decreasing the study’s rigor and invalidating its results. In addition, the symptom intensities are subjective as they are volunteer responses. Also, MSG is essentially salt – and consuming 9 grams of salt is bound to cause some negative reaction. In actuality, MSG causes no harm in moderation 6,7. It’s like any salt: it makes food taste great, but too much can poorly affect your health.

Following Schaumburg’s study, many academic articles cropped up in response. In 1969, a psychiatrist named John Olney claimed that MSG caused brain damage8. Olney injected young mice with 4-7 milligrams of MSG per gram of body weight, equaling approximately 40 milligrams per mouse. This dose is equivalent to an adult human eating a pound of MSG in a single sitting, which is completely impractical. Olney reported that the 40 milligram dose caused these young mice to develop brain lesions and obesity. Olney worried about how MSG might affect developing fetuses and children, so he advised pregnant women to avoid MSG. Many articles have refuted Olney’s study, explaining that MSG is orally ingested and not injected. Current scientific literature also states that MSG cannot passively cross biological membranes like the blood-brain barrier or the placenta, meaning that MSG poses little to no direct effect on fetal development.

The scientific landscape has changed with time, and modern studies with as little academic rigor as Dr. Schaumberg’s are few and far between. However, this study highlights why research needs to be extensively peer-reviewed by multiple reviewers. Research cannot be conducted in a vacuum, so scientists must rely on the community of reviewers, collaborators, and the public to critically evaluate their work. We as readers also need to carefully read the entire article, methods included, because the conclusions may not be as accurate and rigorous as we would hope!

TL;DR

- Monosodium glutamate (MSG) is a salt that is added to many East Asian foods to enhance their umami, or savory, flavor.

- MSG’s bad reputation began with a joke article by Dr. Howard Steel in the New England Journal of Medicine detailing negative symptoms he experienced while eating Chinese American food.

- Dr. Herbert H. Schaumburg and others published dubiously conducted studies spreading the misconception that MSG caused severe symptoms like chest tightness and brain damage.

- It’s important to stay vigilant in recognizing questionable research methods and conclusions to avoid the spread of harmful misconceptions.

Reference

1. Lindemann, B., Ogiwara, Y., & Ninomiya, Y. (2002). The Discovery of Umami. Chemical Senses, 27(9), 843–844. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/27.9.843

2. Löliger, J. (2000). Function and Importance of Glutamate for Savory Foods. The Journal of Nutrition, 130(4), 915S-920S. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/130.4.915S

3. Häuser, W., Hansen, E., & Enck, P. (2012). Nocebo Phenomena in Medicine. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International, 109(26), 459–465. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2012.0459

4. Schaumburg, H. H., Byck, R., Gerstl, R., & Mashman, J. H. (1969). Monosodium L-Glutamate: Its Pharmacology and Role in the Chinese Restaurant Syndrome. Science, 163(3869), 826–828. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.163.3869.826

5. Anderson, G. (2008). Gender differences in pharmacological response. International Review of Neurobiology, 83. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0074-7742(08)00001-9

6. Wahlstedt, A., Bradley, E., Castillo, J., & Burt, K. G. (2022). MSG Is A-OK: Exploring the Xenophobic History of and Best Practices for Consuming Monosodium Glutamate. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 122(1), 25–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2021.01.020

7. Ahdoot, E., & Cohen, F. (2024). Unraveling the MSG-Headache Controversy: An Updated Literature Review. Current Pain and Headache Reports, 28(3), 119–124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-023-01198-z

8. Olney, J. W. (1969). Brain lesions, obesity, and other disturbances in mice treated with monosodium glutamate. Science (New York, N.Y.), 164(3880), 719–721. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.164.3880.719

Pingback: Is MSG bad for you? How the ingredient got a bad reputation—and why it’s changing - Indian Opinion

Pingback: Is MSG bad for you? How the ingredient got a bad reputation—and why it’s changing – Over View – Your Daily News Source

Thanks for clearing this up! It’s amazing how a joke and some flawed studies shaped so many people’s fear of MSG. Knowing that MSG is just a flavor enhancer found naturally in many foods really puts things in perspective. Science literacy is key to cutting through myths like this!