By Laura Odom

If you watched HBO’s House of the Dragon this summer, you might be missing all the dragon- and family-centered drama right about now. If so, don’t worry – here’s a new dragon family tree to become invested in!

This story takes place in our own world and features a real-life dragon: the Komodo dragon. This formidable lizard is native to the Indonesian islands, including the titular Komodo island. As the largest lizard species in the world, the Komodo dragon uses its massive 7-9-foot-long body to knock down prey as large as water buffalo – and sometimes even humans. If the Komodo dragon can’t dispatch its prey with simple tackle-and-chomp tactics, it uses a lethal back-up plan. The dragon’s saliva, which contains highly septic bacteria strains and an anticoagulating venom, causes prey to succumb to sepsis, blood loss, and shock within 24 hours. The dragon’s predatory prowess is morbidly fascinating, but I want to instead highlight a different ability it possesses, one centered around giving life instead of taking it. Observations of a captive Komodo dragon (Figure 1) in 2006 unexpectedly revealed that these creatures are capable of parthenogenesis, the ability to reproduce asexually without fertilization by sperm.

If asked to name some asexual reproducers, most would probably bring up primordial organisms like archaea and bacteria, or perhaps plants, fungi, and invertebrates like jellyfish polyps. However, naturally occurring asexual reproduction exists in numerous vertebrates, including fish, birds, and reptiles. So, how – and why – do vertebrates, including the Komodo dragon, reproduce via parthenogenesis? Let’s talk about self-love.

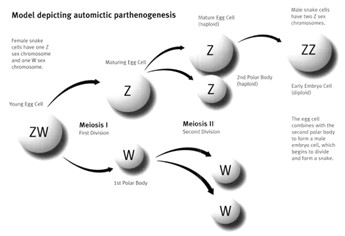

We’re familiar with chromosomes and know that in most mammalian species, including humans, the sex chromosomes are X and Y: biological females have 2 X chromosomes and biological males have an X and a Y chromosome. However, many species of birds, reptiles, fish, and insects use the ZW sex-determination system in which ZW individuals are female, ZZ individuals are male, and WW individuals are usually nonviable. A female Komodo dragon with ZW sex chromosomes can mate with a male dragon (ZZ) to produce female (ZW) or male (ZZ) offspring. Alternatively, if a female Komodo dragon finds herself isolated from males (quite possible in her native island chain habitat, or, say, while in captivity), she can undergo parthenogenesis, duplicating one set of her maternal chromosomes to produce only ZZ sons. Parthenogenesis occurs in a mature oocyte (egg cell) after it’s been separated from a polar body in meiosis, the process of sex cell division (Figure 2). During meiosis, an oocyte with two sets of chromosomes (diploid) splits to form a maturing oocyte and polar body, each with only one set of chromosomes (haploid). Polar bodies are meiotic “by-product” cells that don’t normally contribute to zygote (fertilized egg) formation – in human reproduction, the zygote is formed by the fusion of egg and sperm. However, in the case of automictic parthenogenesis in Komodo dragons, the polar body fuses with the mature oocyte in a process aptly named terminal fusion, leading to a diploid zygote – no sperm necessary!

There are a few types of parthenogenesis utilized by other species that I won’t describe now, but you can read more about them here. While some species like Komodo dragons can undergo facultative (as-needed) parthenogenesis, many species cannot undergo parthenogenesis naturally. Mammals cannot reproduce parthenogenetically due to genomic imprinting, the epigenetic process that results in the differing expression of certain genes based on whether they come from the mother or the father. Genomic imprinting balances the expression of maternal and paternal genes, and some of this DNA-level activity is essential for embryonic development in mammals.1

Mammals can’t naturally reproduce asexually, but that hasn’t stopped scientists from inducing a few “immaculate conceptions.” The most notable of these experiments was the creation of Kaguya the fatherless mouse (Figure 3).2 Kaguya was a parthenogenetically conceived mouse created by researchers at the Tokyo University of Agriculture in Japan. Researchers took normal, mature oocytes and combined each with an immature oocyte genetically modified to silence the H19 gene and express the insulin-like growth factor 2 (Igf2) gene. Deletion of the typically maternally imprinted H19 gene reduced the immature oocyte’s chances of being recognized as “mom.” The expression of Igf2, which is normally expressed by the paternal copy of the gene, allowed the immature oocyte to mimic “dad” and facilitate paternal imprinting. As the sole success from 460 attempts at this designer conception, Kaguya grew to adulthood and had her own offspring (the old-fashioned way!), proving the possibility of creating genetically fit offspring through artificial parthenogenesis.

Researchers have since studied artificial parthenogenesis in numerous species, including the humble D. melanogaster (check out Paige’s 2023 LTS article on parthenogenetic research in fruit flies and its implications for pest control)! As gene editing becomes more sophisticated, scientists continue to study parthenogenesis using varied methods. In 2022, researchers at the Center for Reproductive Medicine in Shanghai, China generated viable offspring from single murine oocytes implanted into mouse foster mothers.3 The group used Cas9 and Cpf1 technologies for the targeted DNA methylation (silencing) of imprinting control regions that regulate the expression and function of genes that undergo genomic imprinting, like H19 and Igf2.

This experiment and others of its kind are impressive scientific feats, but the implications of mammalian parthenogenetic research are controversial. The authors of the 2022 study stated that their research “opens many opportunities in agriculture, research, and medicine.”3 However, some have called into question this vague impact statement, stating that “Nontraditional reproductive technologies require a medical benefit in order to be ethically acceptable.” It’s important to consider the biological and societal benefits and drawbacks of humans potentially – someday – being able to have offspring without sperm, either with an individual’s eggs alone or combined with eggs from another human. This concept has been periodically explored in science fiction, appearing in the literary canon as early as 1915 in Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland. The possibility of sperm-less reproduction encompasses several contentious subjects, including women’s reproductive rights, LGBTQ+ rights, and the intersection of religion, science, philosophy, and legislation. Like cloning, artificial parthenogenesis is an innovative reproductive technology that requires ongoing ethical consideration. Producing viable parthenogenetic human offspring is still merely an idea, but scientists have found immense utility in human parthenogenesis for another purpose: stem cell production.

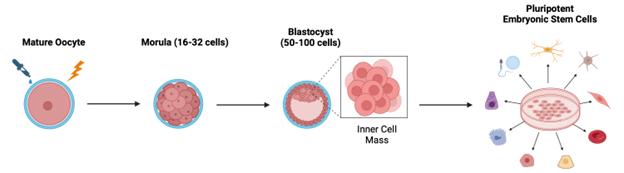

Human stem cell harvesting has long been an ethical battleground based on concerns with exploiting human embryos and defining life and personhood. These concerns arose because, historically, most embryonic stem cells used in research were left over from in vitro fertilizations, or more rarely, from abortions.4 Parthenogenetic embryos don’t circumvent all these concerns, but they do have the advantage of not requiring fertilization. To create a parthenogenetic embryo, oocytes are chemically, electrically, or mechanically stimulated in vitro to encourage cell division (Figure 4).5,6 With the right experimental conditions, oocytes can divide up to the blastocyst stage wherein the embryo consists of 50-100 cells. The blastocyst’s inner cell mass is then harvested, yielding pluripotent embryonic stem cells (ESCs). ESCs can differentiate into cells and tissues of all three germ layers that make up organs. Therefore, they are of great value in regenerative medicine.

Parthenogenetically derived ESCs have been studied for numerous medical applications, including treatment of neurodegenerative diseases and cell repopulation in the liver and heart.7,8,9 Oocytes can be manipulated after the first or second rounds of meiosis (Figure 2) to produce ESCs that are either homozygous or heterozygous, respectively, for the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) gene cluster. HLA heterozygous ESCs can be used for autologous transplantation, or the reintroduction of an individual’s stem cells into their body for regenerative medicine. HLA homozygous ESCs can theoretically be used for allogeneic transplantation (using stem cells from someone other than the patient); however, it turns out that the immune system is complex and doesn’t like to be messed with. Therefore, circumventing barriers in the recognition of stem cells by the immune system’s natural killer cells is a current priority in parthenogenetic ESC research.10

Artificial parthenogenesis challenges our collective understanding of reproductive science. Taking inspiration from parthenogenesis-capable species like the Komodo dragon, scientists have identified new possibilities in what we previously believed to be a highly conventional and dogmatic process of mammalian reproduction. While not quite as dramatic as an episode of House of the Dragon, the field of parthenogenetic stem cell research is rife with discord and ethical quandaries. However, keeping important ethical considerations in mind, the ongoing study of parthenogenetic stem cells has the potential to revolutionize personalized and regenerative medicine.

TL;DR

- Komodo dragons can undergo parthenogenesis, the production of offspring without fertilization by sperm, wherein a mature oocyte fuses with a polar body after meiosis

- Mammals can’t naturally reproduce parthenogenetically, but researchers have induced parthenogenesis in several species using gene editing technologies

- Parthenogenetic research is ethically controversial, but its utility in producing embryonic stem cells is instrumental for regenerative medicine

Reference

- Plasschaert, R. N., & Bartolomei, M. S. (2014). Genomic imprinting in development, growth, behavior and stem cells. Development (Cambridge, England), 141(9), 1805–1813. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.101428

- Kono, T., Obata, Y., Wu, Q., Niwa, K., Ono, Y., Yamamoto, Y., Park, E. S., Seo, J.-S., & Ogawa, H. (2004). Birth of parthenogenetic mice that can develop to adulthood. Nature, 428(6985), 860–864. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02402

- Wei, Y., Yang, C.-R., & Zhao, Z.-A. (2022). Viable offspring derived from single unfertilized mammalian oocytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(12). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2115248119

- Lagay, F. (2001). Sources of Embryonic Stem Cells for Research. AMA Journal of Ethics, 3(2). https://doi.org/10.1001/virtualmentor.2001.3.2.jdsc1-0102

- Hosseini, S. M., Hajian, M., Moulavi, F., Shahverdi, A. H., & Nasr-Esfahani, M. H. (2008). Optimized combined electrical–chemical parthenogenetic activation for in vitro matured bovine oocytes. Animal Reproduction Science, 108(1-2), 122–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anireprosci.2007.07.011

- Han, B., & Gao, J. R. (2013). Effects of chemical combinations on the parthenogenetic activation of mouse oocytes. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine, 5(5), 1281–1288. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2013.1018

- Semechkin, R., Isaev, D., Abramihina, T., Turovets, N., West, R., Zogovic-Kapsalis, T., & Semechkin, A. (2011). 100. Human Neural Stem Cells of Parthenogenetic Origin. Molecular Therapy, 19, S40. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1525-0016(16)36672-2

- Espejel, S., Eckardt, S., Harbell, J., Roll, G. R., McLaughlin, K. J., & Willenbring, H. (2014). Brief Report: Parthenogenetic Embryonic Stem Cells are an Effective Cell Source for Therapeutic Liver Repopulation. STEM CELLS, 32(7), 1983–1988. https://doi.org/10.1002/stem.1726

- Rikhtegar, R., Pezeshkian, M., Dolati, S., Safaie, N., Afrasiabi Rad, A., Mahdipour, M., Nouri, M., Jodati, A. R., & Yousefi, M. (2019). Stem cells as therapy for heart disease: iPSCs, ESCs, CSCs, and skeletal myoblasts. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 109, 304–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2018.10.065

- Yu, Z., & Han, B. (2016). Advantages and limitations of the parthenogenetic embryonic stem cells in cell therapy. Journal of Reproduction and Contraception, 27(2), 118–124. https://doi.org/10.7669/j.issn.1001-7844.2016.02.0118