By Seth Kabonick

The animal kingdom relies on microbes that have co-evolved with their hosts for millions of years. Symbiotic bacteria are beneficial bacteria that fulfill a necessary role defending against pathogens, regulating the immune system, and breaking down dietary nutrients. For this reason, most topical microbiome research emphasizes the host’s influence on microbes; however, symbiotic relationships are a two-way street, which begs the question: how do microbes tell us what they want?

Bacteria feed on host nutrients to survive in the cramped intestinal environment and release molecules humans can use as energy. Resident microbes have dietary restrictions because of their relatively small genomes (approximately 4-6 megabases in comparison to the human genome that has 3,000 megabases) and can only access nutrients they can digest. This means, for better or worse, human dietary choices shape a unique microbiome landscape that is either beneficial or detrimental to your health. Humans have done a fabulous job bullying our microbes by consuming staggering amounts of refined sugars, like high fructose corn syrup, that lower overall bacterial diversity and can initiate or exacerbate human pathologies, like intestinal bowel disease (IBD)1.

The complexity of a complete microbiome makes it nearly impossible to listen to all the microbes in our gut. Many of my friends work in elementary classrooms (which I do not envy), and they frequently encounter the same problem. Trying to address this question is like having a classroom of third graders divulge into a chaos of answers after being asked their favorite food. In the same way, the crowded microbiota produces many metabolites that coordinate signals within the host’s gut-brain axis. To reduce this noise, microbiologists utilize gnotobiotic, or germ-free, mice that have not been colonized by any bacteria from conception. Using this valuable tool, we can introduce single species or well-defined communities of bacteria into the mice and ask reductionist questions about commensal colonization or host interactions.

The lab of Elain Hsiao at UCLA employed this model to determine if microbial species can influence host dietary preference2. Put another way, does a mouse’s preferred diet shift depending upon the food their microbial friends consume? The lab chose two prominent gut bacteria from the genus Bacteroides, which constitutes nearly half of all bacteria in an average microbiota3. These bacteria are exceptional digestors of dietary fiber that cannot be accessed by the host; however, many can only access certain types of sugars. Sugar structures are tricky to understand because they might be composed of one type of sugar, such as fructose, but stitched together in two different ways. For example, levan and inulin are both chains of fructose but take on different structures. Linkages are important because levan and inulin could be accessible to one bacterial species, but inaccessible to another. Therefore, it is sugar linkages which dictate microbial accessibility.

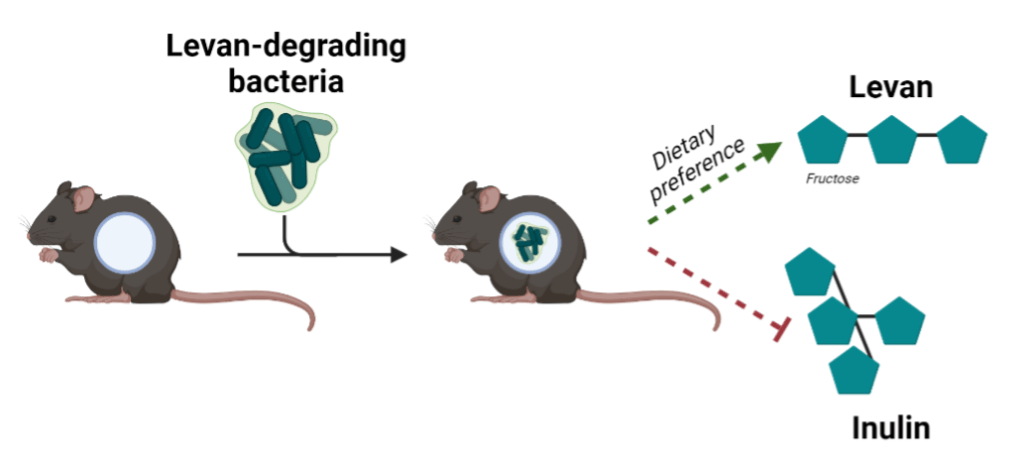

The Hsiao lab exploits the specificity of levan and inulin by performing mono-colonization (or single species) experiments in a mice cohort with two dietary choices: sugars that can be accessed by the microbes and sugars that cannot (Fig. 1). Surprisingly, results show that mice would exhibit a dietary preference for a sugar that can be utilized by the resident microbes, suggesting microbes influence host decision on which foods to consume. Alongside this experiment, researchers also designed mutant microbes unable to access the dietary sugars to confirm that 1) the dietary effects were dependent upon resident microbes and 2) that the dietary sugars directly caused the change in eating habits. Confirmatory results showed mice colonized with mutants unable to access dietary sugars completely absolved the mouse’s food preference.

Possibly the most striking finding was changes in a mouse’s dietary preference corresponded to changes in neuronal signaling, indicating the breakdown of sugars by commensal bacteria affects signals across the gut-brain axis. They propose microbes break down sugars and release molecules in the intestine that can provide the host energy. Your body’s “sensing” of this energy promotes a signaling cascade that culminates with a desire to consume more of that sugar type.

These findings open a new possibility to a previously unaddressed idea: our gut bacteria influence host choices by providing us with nutrients from our diet. Expounding upon this idea might reveal the microbiome as the ultimate puppeteer of your subconscious decisions. So, take care of them with a diverse diet that feeds both you and your microbes (even if you’re a busy graduate student)!

TL;DR

- The human gut is colonized by microbes with different types of metabolic capabilities.

- Research from the Hsiao lab shows the type of bacteria, and their metabolic capabilities shift the host’s appetite towards a diet the bacteria can breakdown.

Reference

- Khan, S. et al. Dietary simple sugars alter microbial ecology in the gut and promote colitis in mice. Sci Transl Med 12 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aay6218

- Yu, K. B. et al. Complex carbohydrate utilization by gut bacteria modulates host food preference (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, 2024).

- Zafar, H. & Saier, M. H., Jr. Gut Bacteroides species in health and disease. Gut Microbes 13, 1-20 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2020.1848158