By Olivia Marx

The following is a summary of my PhD thesis work entitled “Transcriptomic Characterization of Early-onset Colorectal Cancer”, which I will defend on July 25th, 2024. I’m so glad to be able to share it with everyone. Thanks to LTS for this opportunity to share my dissertation with more than the four people who did read all 160 pages of it.

People are getting colon cancer at younger and younger ages.

As a person ages, their cells may accumulate mutations – changes in the DNA sequence – that eventually lead to cancer, a disease defined by uncontrolled cell growth1. Recently, however, people have started getting colon and rectal cancer (CRC) earlier in life. This is largely attributed to a changing global lifestyle. Unhealthy diet, obesity, and alcohol consumption increase the risk of developing CRC early on2. CRC begins when cells grow uncontrollably and it is often caused by a mutation in a gene, or piece of DNA, that regulates growth. As these cells grow and multiply, they form masses known as polyps or adenomas in the colon and rectum. If caught early, these polyps can be removed before they can turn into cancer, which is why colon cancer screening is so important.

United States guidelines were recently updated to recommend colorectal cancer screenings begin at age 45 (previously 50) 3-6. Unfortunately, younger patients take longer to be diagnosed with CRC, and cancer is often found at later stages, leading to a worse prognosis7-9. Sadly, early-onset CRC (EOCRC) survival chances are lower in the United States for people of color due to limited access to healthcare and understudied genetic risk factors 10, 11. Therefore, understanding how mutations in DNA cause EOCRC is crucial for developing better treatments.

How can we treat EOCRC? First, we need to learn more.

The challenge with cancer treatment isn’t just killing the cancer cells – it’s keeping the rest of the body healthy, and only selectively killing the cancer. Traditionally, CRC is treated through surgical removal of the primary tumor, which is very effective against early-stage cancers. Unfortunately, once the cancer metastasizes (spreads) to other parts of the body, it is nearly impossible to surgically remove. Oncologists also use chemotherapy or radiation to target rapidly dividing cells, both of which come with uncomfortable side effects and often fail to kill all tumor cells, allowing for future relapse. Patients with CRC are usually poor candidates for immunotherapy, the process of enhancing the body’s immune response to eliminate tumor cells. However, some CRCs that are microsatellite instable do respond to immunotherapy.

Microsatellite instability occurs in tumors with defects in cellular DNA repair machinery. These defects lead to a high frequency of mutations in tumor cells. Because these mutations differentiate tumor cells from regular cells, it is easier for the immune system to target and kill them. Interestingly, EOCRC has a higher total number of mutations (“mutational burden”) compared to late-onset CRC, suggesting that younger CRC patients may be better candidates for immunotherapy12. This distinction between EOCRC and CRC highlights the importance of tailoring a cancer treatment to a specific cancer for personalized treatment.

Gene expression can give insight into how to better treat EOCRC.

Personalized treatments have seen successes in other cancer types, such as treatments targeting breast cancers expressing different protein markers. CRC physicians similarly use analyses of mutations to determine the best cancer treatments. Interestingly, many EOCRCs have a different frequency of key mutations13 compared to people with later-onset CRC (patients over 50 years old, LOCRC)3, 14, 15.

Despite differences in their suspected causes and disease presentations, treatments for EOCRC and LOCRC currently remain the same16. Therefore, it is important to better understand the unique aspects of EOCRC to better treat these patients. Even though previous studies have looked at the mutations in EOCRC, few have looked at the functional effect of these mutations.

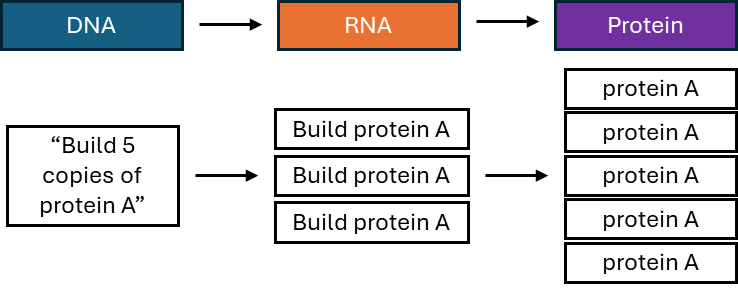

To explore this, during my thesis work, my lab characterized the messenger RNA (mRNA) sequences of EOCRC patients. Cells use DNA as a template to make several types of RNA, and mRNA serves as a template for proteins (Figure 1). Think of DNA as the instructions to build multiple components of a Lego cell, but the instructions can’t leave the house, and the Legos can’t go into the house. So, you make a copy of the instructions, removing the extra information that’s not needed. You make extra copies of the parts that you will need more of, and hand them out to all your little friends to build.

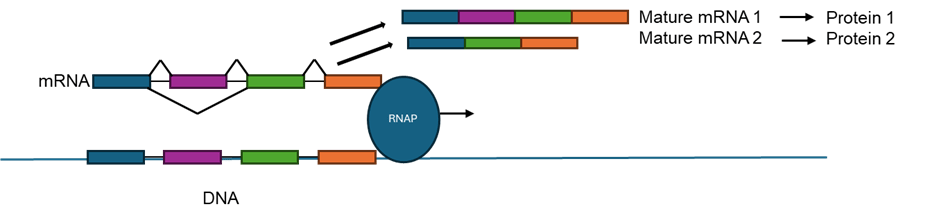

In biology terms, the DNA sequence, the instructions for the cell, works though producing varying amounts of the important intermediary molecule RNA to make the diverse set of proteins needed for each individual cell. For researchers, looking at units of RNA (also known as transcripts) from a gene can give a detailed picture of how much of a certain protein will be expressed in a cell. Furthermore, RNA undergoes a process called splicing, where different sequences can either be kept in or cut out of the final transcript (Figure 2). Changing the amount or sequence of an RNA can affect cancer development and growth, and thus, understanding the mRNA profile of EOCRC can help understand what medicines might be used to selectively kill the cancer cells in patients.

My dissertation work: characterizing gene expression in EOCRC

My dissertation work is summarized in Figure 3. In brief, we focused on profiling the transcriptomes, the total amount of RNA in the cell, of 21 EOCRC patients who had their CRC tumors surgically removed at the Penn State College of Medicine. My project began with performing RNA-sequencing, a technique used to analyze all the RNA transcripts in a cell, on 21 pairs of tumors and non-cancerous samples. These patients’ tumors and normal colonic tissues were saved in the Carlino Family Inflammatory Bowel and Colorectal Disease Biobank.

My project found that the transcription factor MYC was deregulated; there was more MYC mRNA in cancers compared to normal tissues from EOCRC patients. This wasn’t that shocking: MYC is changed in up to 70% of all cancers17. We found that higher or lower expression of MYC could separate patients into two groups, with the higher MYC-expressing group associated with obesity. We also showed that in half of the high MYC-expressing patients, the MYC gene had at least one extra DNA copy, causing increased expression. In contrast, CRC has only 8-15% of tumors with an increase in MYC DNA copy number18, indicating a unique way in which MYC may be regulated in EOCRC.

Our next move: find genes that behave differently in EOCRC for targeted treatments

We put together a group of LOCRC samples from the biobank that had similar patient characteristics as the EOCRC group. This way the two groups were comparable, with differences in age and not things like tumor stage, which can also affect gene expression.

We first found eight genes that were differentially expressed (read: acting weird) in EOCRC tumors versus normal samples, but these genes didn’t exhibit that same behavior in LOCRC tumors. Together, the expression of these genes corresponded with significantly worse patient survival, supporting their relevance to cancer.

We also used gene expression data to predict what cell types surrounded the EOCRC and LOCRC tumors and normal tissues. We found significant differences in immune cell populations in EOCRC compared to LOCRCs, which suggested EOCRCs might have more immune cell activity surrounding the tumor, supporting that EOCRCs might respond differently to immunotherapies.

Lastly, we looked at alternative mRNA splicing in EOCRC versus LOCRC. mRNA splicing is crucial for development and cancer; however, it had never been examined in EOCRC before19. We found that RNA splicing was distinct in EOCRC and LOCRC patients and that many of the genes that were uniquely spliced in EOCRC tumors were involved in immune activity. Together with previous studies, this suggests that younger patients’ immune systems may respond differently to CRC compared with older patients.

What’s next?

The work in my dissertation provides a preliminary – but enlightening – glimpse into the transcriptome of EOCRC. In the future, biobanks from more individuals and tissues will expand, providing more sequencing data and an even more in-depth view of the EOCRC transcriptome. Although the patients from this study were mostly white, efforts are being made to increase the diversity of biobanks. Having diverse patient samples allows treatments to be adapted to different genetic backgrounds, ensuring that future medications can effectively treat the whole patient population.

In addition, further exploration of immunotherapy for EOCRC patients can determine if they would benefit more than their older counterparts. Meanwhile, although MYC – the gene whose expression we found to be dysregulated in EOCRC – is notoriously difficult to target, recent studies have had success in targeting it and killing cancer cells20, 21. So, it may be a good future target for EOCRC treatments. Overall, the important differences identified between young and old colorectal cancers will inform personalized, future cancer treatments.

As for me, I’m so grateful I got to contribute to this project. It inspired a huge appreciation for patient-centered data, and I am so excited I get to continue researching human health for the next step of my career. For my next position, I am moving to the opposite end of the digestive system: the mouth. That’s right, I have accepted a post-doctoral position at the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research to study salivary disorders.

TL:DR

- There has been a global rise in colorectal cancer in people under 50 years old

- The transcription factor MYC and its downstream targets are deregulated in early-onset colorectal cancers

- Colorectal cancer in young patients is distinct from that in older patients

- Future studies should focus on growing diverse biobanks, as well as exploring differences in immunotherapy and targeted treatment responses in early versus later onset colorectal cancers

Reference

1. Sinkala M. Mutational landscape of cancer-driver genes across human cancers. Scientific Reports. 2023;13(1):12742. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-39608-2.

2. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Fedewa SA, Butterly LF, Anderson JC, Cercek A, Smith RA, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(3):145-64. Epub 20200305. doi: 10.3322/caac.21601. PubMed PMID: 32133645.

3. Connell LC, Mota JM, Braghiroli MI, Hoff PM. The Rising Incidence of Younger Patients With Colorectal Cancer: Questions About Screening, Biology, and Treatment. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2017;18(4):23. doi: 10.1007/s11864-017-0463-3. PubMed PMID: 28391421.

4. Siegel RL, Wagle NS, Cercek A, Smith RA, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73(3):233-54. Epub 20230301. doi: 10.3322/caac.21772. PubMed PMID: 36856579.

5. Wender RC. Colorectal cancer screening should begin at 45. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;35(9):1461-3. doi: 10.1111/jgh.15196. PubMed PMID: 32944996.

6. Wolf AMD, Fontham ETH, Church TR, Flowers CR, Guerra CE, LaMonte SJ, Etzioni R, McKenna MT, Oeffinger KC, Shih YT, Walter LC, Andrews KS, Brawley OW, Brooks D, Fedewa SA, Manassaram-Baptiste D, Siegel RL, Wender RC, Smith RA. Colorectal cancer screening for average-risk adults: 2018 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(4):250-81. Epub 20180530. doi: 10.3322/caac.21457. PubMed PMID: 29846947.

7. Eng C, Jácome AA, Agarwal R, Hayat MH, Byndloss MX, Holowatyj AN, Bailey C, Lieu CH. A comprehensive framework for early-onset colorectal cancer research. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(3):e116-e28. Epub 20220131. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(21)00588-x. PubMed PMID: 35090673.

8. Mauri G, Sartore-Bianchi A, Russo AG, Marsoni S, Bardelli A, Siena S. Early-onset colorectal cancer in young individuals. Mol Oncol. 2019;13(2):109-31. Epub 20181222. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12417. PubMed PMID: 30520562; PMCID: PMC6360363.

9. Chen FW, Sundaram V, Chew TA, Ladabaum U. Advanced-Stage Colorectal Cancer in Persons Younger Than 50 Years Not Associated With Longer Duration of Symptoms or Time to Diagnosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(5):728-37.e3. Epub 20161114. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.10.038. PubMed PMID: 27856366; PMCID: PMC5401776.

10. Muller C, Ihionkhan E, Stoffel EM, Kupfer SS. Disparities in Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer. Cells. 2021;10(5). Epub 20210426. doi: 10.3390/cells10051018. PubMed PMID: 33925893; PMCID: PMC8146231.

11. Siegel RL, Torre LA, Soerjomataram I, Hayes RB, Bray F, Weber TK, Jemal A. Global patterns and trends in colorectal cancer incidence in young adults. Gut. 2019;68(12):2179-85. Epub 20190905. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319511. PubMed PMID: 31488504.

12. Archambault AN, Su YR, Jeon J, Thomas M, Lin Y, Conti DV, Win AK, Sakoda LC, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Peterse EFP, Zauber AG, Duggan D, Holowatyj AN, Huyghe JR, Brenner H, Cotterchio M, Bézieau S, Schmit SL, Edlund CK, Southey MC, MacInnis RJ, Campbell PT, Chang-Claude J, Slattery ML, Chan AT, Joshi AD, Song M, Cao Y, Woods MO, White E, Weinstein SJ, Ulrich CM, Hoffmeister M, Bien SA, Harrison TA, Hampe J, Li CI, Schafmayer C, Offit K, Pharoah PD, Moreno V, Lindblom A, Wolk A, Wu AH, Li L, Gunter MJ, Gsur A, Keku TO, Pearlman R, Bishop DT, Castellví-Bel S, Moreira L, Vodicka P, Kampman E, Giles GG, Albanes D, Baron JA, Berndt SI, Brezina S, Buch S, Buchanan DD, Trichopoulou A, Severi G, Chirlaque MD, Sánchez MJ, Palli D, Kühn T, Murphy N, Cross AJ, Burnett-Hartman AN, Chanock SJ, de la Chapelle A, Easton DF, Elliott F, English DR, Feskens EJM, FitzGerald LM, Goodman PJ, Hopper JL, Hudson TJ, Hunter DJ, Jacobs EJ, Joshu CE, Küry S, Markowitz SD, Milne RL, Platz EA, Rennert G, Rennert HS, Schumacher FR, Sandler RS, Seminara D, Tangen CM, Thibodeau SN, Toland AE, van Duijnhoven FJB, Visvanathan K, Vodickova L, Potter JD, Männistö S, Weigl K, Figueiredo J, Martín V, Larsson SC, Parfrey PS, Huang WY, Lenz HJ, Castelao JE, Gago-Dominguez M, Muñoz-Garzón V, Mancao C, Haiman CA, Wilkens LR, Siegel E, Barry E, Younghusband B, Van Guelpen B, Harlid S, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A, Liang PS, Du M, Casey G, Lindor NM, Le Marchand L, Gallinger SJ, Jenkins MA, Newcomb PA, Gruber SB, Schoen RE, Hampel H, Corley DA, Hsu L, Peters U, Hayes RB. Cumulative Burden of Colorectal Cancer-Associated Genetic Variants Is More Strongly Associated With Early-Onset vs Late-Onset Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(5):1274-86.e12. Epub 20191219. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.12.012. PubMed PMID: 31866242; PMCID: PMC7103489.

13. Pearlman R, Frankel WL, Swanson B, Zhao W, Yilmaz A, Miller K, Bacher J, Bigley C, Nelsen L, Goodfellow PJ, Goldberg RM, Paskett E, Shields PG, Freudenheim JL, Stanich PP, Lattimer I, Arnold M, Liyanarachchi S, Kalady M, Heald B, Greenwood C, Paquette I, Prues M, Draper DJ, Lindeman C, Kuebler JP, Reynolds K, Brell JM, Shaper AA, Mahesh S, Buie N, Weeman K, Shine K, Haut M, Edwards J, Bastola S, Wickham K, Khanduja KS, Zacks R, Pritchard CC, Shirts BH, Jacobson A, Allen B, de la Chapelle A, Hampel H. Prevalence and Spectrum of Germline Cancer Susceptibility Gene Mutations Among Patients With Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(4):464-71. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5194. PubMed PMID: 27978560; PMCID: PMC5564179.

14. Strum WB, Boland CR. Clinical and Genetic Characteristics of Colorectal Cancer in Persons under 50 Years of Age: A Review. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64(11):3059-65. Epub 20190504. doi: 10.1007/s10620-019-05644-0. PubMed PMID: 31055721.

15. Kneuertz PJ, Chang GJ, Hu CY, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Eng C, Vilar E, Skibber JM, Feig BW, Cormier JN, You YN. Overtreatment of young adults with colon cancer: more intense treatments with unmatched survival gains. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(5):402-9. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.3572. PubMed PMID: 25806815.

16. Benson AB, Venook AP, Al-Hawary MM, Arain MA, Chen YJ, Ciombor KK, Cohen S, Cooper HS, Deming D, Farkas L, Garrido-Laguna I, Grem JL, Gunn A, Hecht JR, Hoffe S, Hubbard J, Hunt S, Johung KL, Kirilcuk N, Krishnamurthi S, Messersmith WA, Meyerhardt J, Miller ED, Mulcahy MF, Nurkin S, Overman MJ, Parikh A, Patel H, Pedersen K, Saltz L, Schneider C, Shibata D, Skibber JM, Sofocleous CT, Stoffel EM, Stotsky-Himelfarb E, Willett CG, Gregory KM, Gurski LA. Colon Cancer, Version 2.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19(3):329-59. Epub 20210302. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2021.0012. PubMed PMID: 33724754.

17. Dong Y, Tu R, Liu H, Qing G. Regulation of cancer cell metabolism: oncogenic MYC in the driver’s seat. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. 2020;5(1):124. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00235-2.

18. Marx O, Mankarious M, Yochum G. Molecular genetics of early-onset colorectal cancer. World J Biol Chem. 2023;14(2):13-27. doi: 10.4331/wjbc.v14.i2.13. PubMed PMID: 37034132; PMCID: PMC10080548.

19. Marx OM, Mankarious MM, Koltun WA, Yochum GS. Identification of differentially expressed genes and splicing events in early-onset colorectal cancer. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1365762. Epub 20240411. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2024.1365762. PubMed PMID: 38680862; PMCID: PMC11047122.

20. Han H, Jain AD, Truica MI, Izquierdo-Ferrer J, Anker JF, Lysy B, Sagar V, Luan Y, Chalmers ZR, Unno K, Mok H, Vatapalli R, Yoo YA, Rodriguez Y, Kandela I, Parker JB, Chakravarti D, Mishra RK, Schiltz GE, Abdulkadir SA. Small-Molecule MYC Inhibitors Suppress Tumor Growth and Enhance Immunotherapy. Cancer Cell. 2019;36(5):483-97.e15. Epub 20191031. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.10.001. PubMed PMID: 31679823; PMCID: PMC6939458.

21. Garralda E, Beaulieu ME, Moreno V, Casacuberta-Serra S, Martínez-Martín S, Foradada L, Alonso G, Massó-Vallés D, López-Estévez S, Jauset T, Corral de la Fuente E, Doger B, Hernández T, Perez-Lopez R, Arqués O, Castillo Cano V, Morales J, Whitfield JR, Niewel M, Soucek L, Calvo E. MYC targeting by OMO-103 in solid tumors: a phase 1 trial. Nat Med. 2024. Epub 20240206. doi: 10.1038/s41591-024-02805-1. PubMed PMID: 38321218.