By: Natale Hall

Introduction

The art of making a perfectly crusted sourdough loaf dates back to around 2,000 B.C., when the Ancient Egyptians discovered that a combination of flour, water, and environmental contamination resulted in the formation of bubbly and delicious bread1. Four thousand years later, sourdough experienced a massive resurgence in popularity during the COVID-19 pandemic, when a combination of panic over yeast shortages and an abundance of time at home inspired thousands to take up bread making2. If you have ever watched a video on the sourdough-making process, or perhaps endeavored to make your own loaf, then you may be wondering how a recipe consisting of three ingredients can be so complicated. From precisely measuring out each component with a kitchen scale to timing each step down to the second, making a loaf of sourdough feels a lot like conducting an at-home science experiment. Creating sourdough is a highly scientific process rooted in microbiology and chemistry. From the early stages of cultivating the starter to the final overnight proof, every meticulous step in the sourdough process holds a fascinating scientific explanation that transforms simple ingredients into a flavorful, beloved loaf.

Getting started with the starter

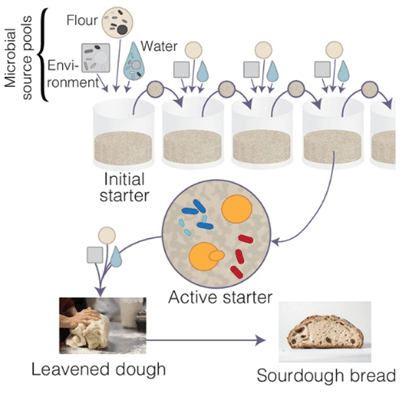

Sourdough bread begins as a humble starter. A mixture of flour and water is colonized by two types of microbes: yeast and bacteria. These microorganisms naturally exist in the flour used to create the starter but can also come from the air, water, and container holding the starter. While the idea of microbes in bread may sound alarming, the yeast and bacteria are essential to the final product.

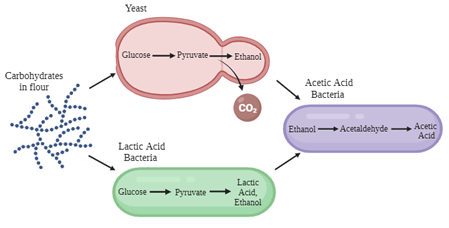

Yeast are single-celled fungi that function as the main leavening agent in sourdough, giving the sourdough its characteristic bubbles and allow it to rise3. The yeast accomplish this by undergoing anaerobic metabolism, or fermentation, in the low-oxygen conditions of the starter. During fermentation, the different types of complex carbohydrates in the flour, including starch, glucofructans, and hemicelluloses, are broken down by various yeast enzymes to yield the sugar molecule: glucose. The glucose is further broken down into pyruvate through a process called glycolysis. In the anaerobic environment of the yeast cells, pyruvate is fermented into ethanol, which produces carbon dioxide gas (CO2) as a by-product. The buildup of CO2 causes bubbles to form, which makes the starter to rise, and eventually is what gives way to the signature bubbles in the final cooked loaf.

Sourdough starters are typically colonized by several hundred species and strains of bacteria4. However, as the starter is maintained, two types of bacteria out-compete the others due to their ability to produce acid and create an acidic environment: namely, lactic acid bacteria (LAB) and acetic acid bacteria (AAB). The more prevalent of the two, LAB, accounts for most of the bread’s taste and texture. Like yeast, LAB digest the flour’s supply of carbohydrates to produce glucose and pyruvate. Then, LAB undergo a second type of anaerobic metabolism called lactic acid fermentation. This process results in the formation of lactic acid, which gives sourdough its unique tangy flavor. On the other hand, the less common AAB produce acetic acid through oxidation of the yeast-made ethanol, also enhancing the bread’s overall taste by adding more sourness to the final flavor5.

Maintaining a starter includes periodically discarding part of the mixture and supplementing it with fresh flour and water in a process called “feeding,” as illustrated in Figure 2. This practice helps maintain a diverse, flourishing microbiome by introducing new species and strains of yeast and bacteria to the culture, which in turn adds to the complex flavor of the final bread.

Stretch and fold!

To make the dough, a portion of the starter is mixed with water, flour, and salt. Then, the dough undergoes a series of kneading followed by rest periods, known as “stretch and fold,”. Stretching and folding speeds up the formation of the gluten network, which is necessary for the chewy and airy texture of the final bread.

Flour, made from wheat, naturally contains two proteins, gliadin and glutenin, that do not dissolve in water6. When water is added to make the dough, these proteins form a viscous mass known collectively as gluten. Initially, the gluten mass is extremely unorganized and, if left unattended, would result in dense, gummy bread. This is where the science of the stretch and fold technique comes into play. By physically maneuvering the gluten proteins in the dough, the proteins become positioned to form more favorable interactions such as disulfide bridges and hydrogen bonds7. Repeating the stretch and fold process causes more of these bonds to form and eventually promotes the organization of the gluten proteins into a secondary structure called β-sheets, shown in Figure 3 below, which are the main structural component of the gluten network8. This network gives sourdough its strength and elasticity, which enables the dough to expand as CO2 is produced from the fermentation process and retains most of this gas in the form of the characteristic bubbles.

Although the bulk of the sourdough-making process is stretching and folding the dough to build up the gluten network, sourdough bread has a relatively low gluten content9. This is because in between each set of stretch and fold, the dough is set aside to rest. Additionally, after the final stretching and folding iteration, the dough is set aside for a final proof, or overnight rest, before being baked. During these rest periods, the yeast and bacteria become more active, producing large quantities of CO2, lactic acid, and acetic acid. Particularly, the acids produced by the LAB and AAB break down some of the gluten proteins in the dough. While sourdough has a highly organized gluten network, it also has less gluten compared to other wheat breads. As a result, some individuals with gluten sensitivities may still be able to enjoy a slice of tasty sourdough!

It’s so much more than bread!

The ancient practice of making sourdough extends far beyond simply baking bread. Routinely feeding starters with fresh flour and water (and yeast and bacteria) means that sourdough starters can be maintained indefinitely5. As such, some starters are hundreds of years old and have been passed down through generations, making them a living piece of history. Additionally, the act of discarding some starter during feeding has led people to give away their extra starter to friends, family, and even strangers. This sharing has helped create a welcoming community of sourdough enthusiasts around the world.

Whether you buy your sourdough from the store or make it at home, remember the fascinating science and rich history behind each yummy slice. Every bite is a blend of biology and tradition: a testament to the wonders of fermentation and the connections formed through a shared love of baking.

TL;DR

- Making sourdough is an ancient practice dating back to 2,000 B.C. in Ancient Egypt

- Sourdough contains CO2-producing yeast that help the bread rise and acid-producing bacteria that give the bread flavor

- Developing the dough’s gluten network is essential to the chewy texture of sourdough

- Starters can be hundreds of years old and are often shared among communities

Reference

1. Cappelle, S., Guylaine, L., Gänzle, M. & Gobbetti, M. History and Social Aspects of Sourdough. in Handbook on Sourdough Biotechnology (eds. Gobbetti, M. & Gänzle, M.) 1–13 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2023). doi:10.1007/978-3-031-23084-4_1.

2. Easterbrook-Smith, G. By Bread Alone: Baking as Leisure, Performance, Sustenance, During the COVID-19 Crisis. Leis. Sci. 43, 36–42 (2021).

3. Maicas, S. The Role of Yeasts in Fermentation Processes. Microorganisms 8, 1142 (2020).

4. Calvert, M. D. et al. A review of sourdough starters: ecology, practices, and sensory quality with applications for baking and recommendations for future research. PeerJ 9, e11389 (2021).

5. Landis, E. A. et al. The diversity and function of sourdough starter microbiomes. eLife 10, e61644 (2021).

6. Alfaris, N. A. et al. Impacts of wheat bran on the structure of the gluten network as studied through the production of dough and factors affecting gluten network. Food Sci. Technol. 42, e37021 (2022).

7. Newman, K. L. Sourdough by Science: Understanding Bread Making for Successful Baking. (The Countryman Press, 2022).

8. Létang, C., Piau, M. & Verdier, C. Characterization of wheat flour–water doughs. Part I: Rheometry and microstructure. J. Food Eng. 41, 121–132 (1999).

9. Lau, S. W., Chong, A. Q., Chin, N. L., Talib, R. A. & Basha, R. K. Sourdough Microbiome Comparison and Benefits. Microorganisms 9, 1355 (2021).

Pingback: Ultimate Sourdough Bread Recipe: Easy and Delicious

Pingback: Friends, Food, and Fighters: How Biotics Shape Your Microbiome | Lions Talk Science