By: Zoe Katz

We may finally have a way to regrow teeth, though the therapeutic compound responsible for this scientific feat is just at the beginning stages of testing in humans.

The field of regenerative medicine aims to design therapies that use our own bodies to heal or regrow tissues to restore them to their original function. Unlike humans, numerous other animals such as fish, amphibians, and sharks retain the life-long ability to regrow lost teeth. Mammals are only able to regrow teeth once1, when we lose and replace our so-called “baby teeth” with permanent teeth. Tooth loss happens naturally throughout life and is commonly seen in populations of older individuals as a result of infection, traumatic injury, or lack of proper dental care2. Teeth are essential in our everyday lives and offer us the ability to chew food and pronounce words. They also affect the shape of our jaws, changing the appearance of our faces3. Loss of teeth may require dentures, tooth implants, or transplants which are the current and most common treatments4. Defects in tooth growth from birth, referred to as tooth agenesis5, are congenital malformations resulting in one or more missing teeth, a common feature of those with cleft lip, cleft palate, and other syndromes5. Limited treatments for lost teeth are expensive, temporary, and do not restore original tooth function4. Additionally, there are no treatments for those with congenital tooth malformations4. For years, scientists have been heavily interested in developing therapeutics to regrow teeth, a feat that was not possible until very recently.

As the first of its kind, a new drug targeting USAG-1, a key protein involved in tooth formation, will enter its Phase I human trials in September 20246, bringing the goal of tooth regeneration in humans within reach. The development of a drug therapy to directly allow for the growth of new teeth is paramount to providing beneficial, function-restoring care and improving quality of life for those affected by tooth loss.

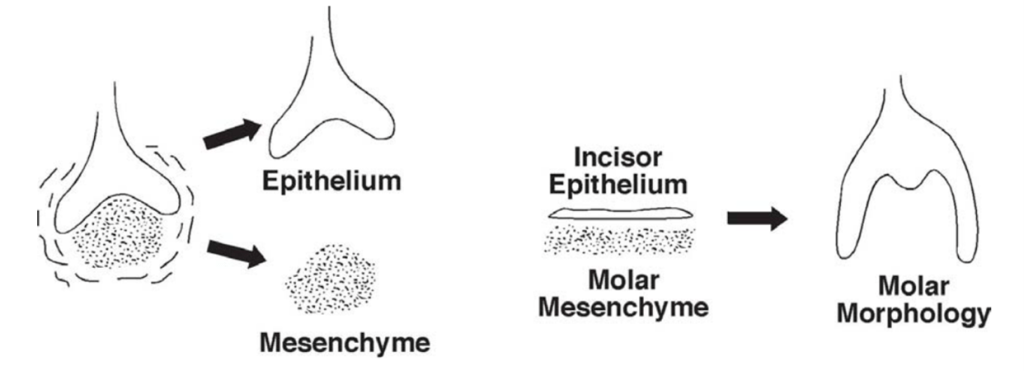

To understand how teeth can be lost both congenitally and throughout life, it is important to first understand how they grow. Occurring from embryonic stages of development through puberty, tooth development is a complex process involving both the dental epithelium and the dental mesenchyme, two tissues that differentiate (mature) into different specialized cell types (Figure 1). Differentiation of dental epithelium results in the generation of cells that produce enamel, the most mineralized tissue in the body which lacks self-healing abilities. Dental mesenchymal tissues differentiate into cells that have functions important for tissue repair and mechanical support to the enamel. Interactions between these tissues are crucial for the formation of teeth (Figure 1)7.

Tooth agenesis, or failure of tooth growth, occurs primarily due to genetic factors, although environmental factors can contribute. Importantly, gene expression throughout tooth development, such as of genes that encode bone morphogenic protein-7 (BMP-7), is crucial for tooth development to allow for cell differentiation as mentioned above. Mutations in the BMP-7 gene result in tooth development inhibition2. The importance of BMP-7 is highlighted by its function as a cell surface receptor (like a little sentinel hanging out in the cell membrane), inducing (telling the cell to do something when it receives a specific signal) dental epithelium differentiation. During development, uterine sensitization-associated gene-1 (USAG-1) is co-expressed with BMP-7 in the same cells: USAG-1 inhibits BMP-7 signaling, inhibiting tooth formation (Figure 2). Studies using mouse models in which both USAG-1 and BMP genes were deleted had decreased tooth size at birth. In contrast, mice with BMP-7 expressed, without USAG-1, showed normal tooth size and less mesenchymal cell death, allowing for normal tissue repair and better support of the enamel8 (Figure 1). Together, these results show that USAG-1 inhibits tooth formation by inhibiting BMP-7 function (Figure 2).

As USAG-1 is a BMP-7 antagonist, or inhibitor, scientists aimed to develop a therapeutic to inhibit USAG-1 and allow for tooth formation in cases of congenital agenesis (remember, that’s defects in tooth growth from birth). Two studies recently were published by the same group in Japan9,10, whereby USAG-1 was inhibited via two different methods to promote tooth growth. One study utilized a local, topically applied short-interfering RNA (siRNA) to target USAG-1 in mice9. siRNAs target genes for degradation before they can be made into proteins, which prevented USAG-1 from being expressed and inhibiting BMP-7 activity. Using USAG-1 siRNA, tooth agenesis was reversed, allowing for tooth development (Figure 2)9.

In a different study, the same group investigated the use of systemically administered antibodies to target USAG-1 and prevent its binding to BMP-7. Antibodies bind to proteins; by binding to USAG-1, the antibody prevented USAG-1 from binding to BMP-7 (Figure 2). Inhibiting USAG-1 alleviated congenital agenesis, allowing for tooth regeneration10. These studies paved the way for breakthroughs in regenerative medicine by developing therapeutics that promote tooth development in people affected by congenital agenesis.

The first human trials are beginning this year in Japan to test the safety of a USAG-1 inhibitor to promote tooth growth6. Safety trials will begin in healthy adult populations before moving to young children to treat congenital tooth agenesis11. As there are currently no treatments for congenital agenesis, and limited treatments for acquired tooth loss, these human trials begin a path toward regenerative tooth treatments. Human trials have not begun yet, so our lost teeth will not be regrowing any time soon; however, hope is on the horizon with this new therapeutic targeting USAG-1.

TL;DR

- Defects in tooth growth can be present at birth (congenital agenesis); loss of permanent teeth can occur throughout life due to a variety of causes

- Current treatments do not restore original tooth function

- A new drug to regenerate teeth, the first of its kind, begins human trials this year

Reference

- Whitlock JA, Richman JM. Biology of tooth replacement in amniotes. Int J Oral Sci. 2013;5(2):66-70. doi:10.1038/ijos.2013.36

- Ye X, Attaie AB. Genetic Basis of Nonsyndromic and Syndromic Tooth Agenesis. J Pediatr Genet. 2016;5(4):198-208. doi:10.1055/s-0036-1592421

- Rakhshan V. Congenitally missing teeth (hypodontia): A review of the literature concerning the etiology, prevalence, risk factors, patterns and treatment. Dent Res J (Isfahan). 2015;12(1):1-13. doi:10.4103/1735-3327.150286

- Ravi V, Murashima-Suginami A, Kiso H, et al. Advances in tooth agenesis and tooth regeneration. Regenerative Therapy. 2023;22:160-168. doi:10.1016/j.reth.2023.01.004

- Ritwik P, Patterson KK. Diagnosis of Tooth Agenesis in Childhood and Risk for Neoplasms in Adulthood. TOJ. 2018;18(4):345-350. doi:10.31486/toj.18.0060

- Rowan Thomas. Tooth regrowth medicine successful in animal trials. Published online June 4, 2024. https://dentistry.co.uk/2024/06/04/tooth-regrowth-medicine-successful-in-animal-trials/#:~:text=It%20works%20by%20suppressing%20USAG,University%20Hospital%20from%20September%202024.

- Fong HK, Foster BL, Popowics TE, Somerman MJ. The Crowning Achievement: Getting to the Root of the Problem. Journal of Dental Education. 2005;69(5):555-570. doi:10.1002/j.0022-0337.2005.69.5.tb03942.x

- Kiso H, Takahashi K, Saito K, et al. Interactions between BMP-7 and USAG-1 (Uterine Sensitization-Associated Gene-1) Regulate Supernumerary Organ Formations. Klymkowsky M, ed. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(5):e96938. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096938

- Mishima S, Takahashi K, Kiso H, et al. Local application of Usag-1 siRNA can promote tooth regeneration in Runx2-deficient mice. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):13674. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-93256-y

- Murashima-Suginami A, Kiso H, Tokita Y, et al. Anti–USAG-1 therapy for tooth regeneration through enhanced BMP signaling. Sci Adv. 2021;7(7):eabf1798. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abf1798

- Anna Kutz. Human trials to begin for new teeth regeneration drug: researchers. https://www.wpri.com/health/human-trials-to-begin-for-new-teeth-regeneration-drug-researchers/?utm_source=fark&utm_medium=website&utm_content=link&ICID=ref_fark