By Ikram Mezghani

Have you ever wondered why certain amphibians can regenerate entire amputated limbs while humans cannot?

Well, you are not alone! Limb regeneration is a superpower that amphibians such as salamanders, newts, and axolotls possess throughout their lifetime. Even though the phenomenon has been observed by many people, amphibian limb regeneration is a question that scientists have been trying to figure out for many centuries. Yet, it was not until the early 18th century that the Italian biologist and physiologist Lazzaro Spallanzani conducted some of the earliest experiments on salamander limb regeneration.

Among the amphibians, the axolotl stands out because of its extraordinary regenerative capabilities. These incredible animals can regenerate and heal almost every single organ in their body, from missing limbs and tails, to damaged hearts, lungs, spine, eye lenses, and even parts of their brains1. This places the axolotl in the spotlight as a key research animal model for scientists to study tissue repair, regeneration, and wound healing. Learning more about how axolotls regrow tissues could help scientists create better treatments for people recovering from difficult injuries, as well as other diseases.

Wound healing: axolotls vs humans

Wound healing is a biological process where damaged cells, tissues, and organs are replaced in response to injury. In mammals, the wound healing process typically results in scar tissue formation to seal the wound site and is a far step away from full tissue regeneration (Fig. 1). Unlike us humans, axolotls have the unique ability to establish true tissue regeneration and complete healing, known as epimorphic regeneration. Similar to wound healing, epimorphic regeneration starts with clot formation to stop bleeding, followed by healing stages that mirror what occurs in human injuries. Epimorphic regeneration, in contrast, goes a step further after clot formation, skips the scar formation step, and instead forms an outgrowth of cells called blastema (Fig. 1). Blastema cells are special types of cells that have remarkable regenerative properties. These cells can quickly grow and transform into different types of cells of the body, such as skin, bone, or even blood vessel cells. This special ability allows blastema cells to completely heal a wound site and even grow entire functional limbs2.

What’s behind the axolotl’s healing superpowers?

Up until recently, little was known about the molecular mechanisms and the key players involved in the axolotls’ rapid healing response – however, a recent study from Dr. Barna’s lab at Stanford university has illuminated a critical piece of the puzzle, a hyperactive protein called Mammalian Target of Rapamycin (mTOR)3.

mTOR is a modifier protein that plays an important role in controlling how cells in our bodies grow, divide, and build other proteins, a process known as protein synthesis. In axolotls, mTOR contains changes in its sequence and structure, which are slightly different from the human mTOR and affect its properties (Fig.2). During early wound healing stages, the axolotls’ unique mTOR structure allows for a hypersensitive response, preparing it for action whenever injury occurs and readying mTOR to start protein synthesis on cue. This hypersensitive mTOR response is only present in amphibians with epimorphic regenerating capabilities, such as axolotls, and is not found in mice nor in humans.

The researchers were able to identify mTOR as the main player guiding the axolotl’s healing process through a method called polysome profiling. Polysomes are mRNAs bound to ribosomes (a non-membranous cellular organelle), which act as small protein factories responsible for protein synthesis. Separating polysomes based on size through a process called sucrose gradient centrifugation helps isolate and profile polysomes of interest (Fig.3). This provides us with a snapshot of proteins actively being made when isolated during specific stages of wound healing.

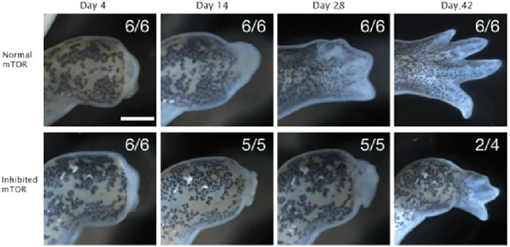

In axolotls, mTOR signaling is needed for initial wound closure and throughout the wound healing process to sustain blastema formation. Following amputation, mTOR shows increased protein production in response to injury, indicating mTOR’s direct involvement in the healing responses. Furthermore, when mTOR is inhibited in injured axolotls, a direct negative effect on the healing process is noticed, resulting in defective limb regeneration, especially during the early stages of healing (Fig. 4).

The discovery of mTOR’s importance to the axolotl wound healing process marks a thrilling leap forward in the field. This exciting finding can pave the way for improving wound healing and regeneration in patients with difficult cases of non-healing, chronic wounds, such as diabetic foot ulcers and burns. Taking these findings to the next steps, engineering an axolotl-like mTOR in human cells will shed light on whether the axolotl mTOR traits can be adapted in humans, allowing us to promote better wound healing treatments, and perhaps even full tissue regeneration. However, there is a long way ahead of us to uncover and understand how the mTOR mechanism plays a role in tissue regeneration and healing in axolotls.

Saving the axolotls: Mexican nuns leading efforts in conservation

We continue to learn valuable insights from axolotls, yet these fascinating creatures face the threat of extinction due to our disruptive practices in their natural habitats. Wild axolotls are found in the high-altitude lakes of Mexico. However, these environments are undergoing detrimental changes due to pollution and global warming. Currently, axolotls are classified as critically endangered animals, and their once-expansive habitats have dwindled to a few inland canals, barely enough to ensure the survival of the species.

Recognizing this dire situation, a dedicated group of nuns in Mexico along with other conservation biologists have taken on a mission to save the axolotl populations through a special breeding program. Their hard work and noble efforts seek not only to preserve the species but also to contribute to the broader understanding of these unique amphibians. In the face of environmental challenges, the nuns’ commitment reflects a hopeful stride towards saving a cherished Mexican icon and restoring the balance in the delicate ecosystems.

TL:DR

- Axolotls are fascinating creatures that can regenerate entire amputated limbs.

- mTOR signaling is important for the initiation and sustainability of the healing and true regeneration process in axolotls.

Reference

- Shieh, S.-J. & Cheng, T.-C. Regeneration and repair of human digits and limbs: fact and fiction. Regen. Oxf. Engl. 2, 149–168 (2015).

- Vieira, W. A., Wells, K. M. & McCusker, C. D. Advancements to the Axolotl Model for Regeneration and Aging. Gerontology 66, 212–222 (2020).

- Zhulyn, O. et al. Evolutionarily divergent mTOR remodels translatome for tissue regeneration. Nature 620, 163–171 (2023).

- Han, C. et al. Polysome profiling followed by quantitative PCR for identifying potential micropeptide encoding long non-coding RNAs in suspension cell lines. STAR Protoc. 3, 101037 (2022).