By Abbey Rebok

DNA, the complex code that defines our existence, is under constant assault by a slew of both exogenous (e.g. UV radiation, tobacco smoke) and endogenous (e.g. spontaneous chemical modifications) DNA-damaging agents. Limiting your exposure to exogeneous agents may decrease your overall DNA damage burden, but normal biological processes also generate DNA damage. Estimates suggest that we experience roughly 10,000 to 100,000 DNA damage events per cell every single day. Yikes. Before your cortisol levels spike, rest assured that your genetic code is not on the precipice of total disaster: fortunately, we have a highly conserved set of DNA repair mechanisms to preserve our genomic integrity. Mutations in proteins necessary for these repair processes may lead to ineffective repair and genomic instability, which is the case for Lynch syndrome, a hereditary condition linked to colorectal cancer. To better understand Lynch syndrome, we need to go back to basics: how DNA copies itself when cells divide, and how cells prevent replication errors.

DNA repair: a crash course

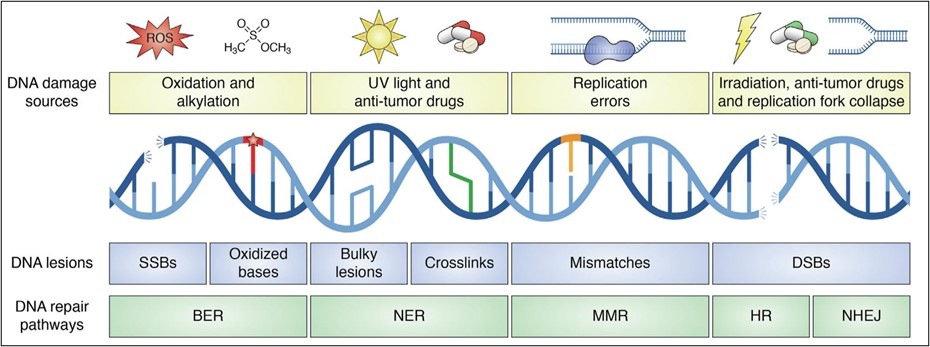

DNA damage exists in an astronomical number of different forms, ranging from bulky adducts (a chemical moiety attached to DNA) to breaks. It may seem reasonable to assume that we’ve evolved an equally substantial set of DNA repair mechanisms to combat them – but in reality, we make do with a small set of broadly effective repair “weaponry” in our DNA defense arsenal. There are five main DNA repair mechanisms: direct repair, base excision repair, nucleotide excision repair, mismatch repair, and double-strand break repair (Figure 1). These five DNA repair systems are robust and can identify and combat the majority of DNA damages. Defects in any of these systems, however, can lead to the formation of mutations and potentially give rise to cancer. In fact, it’s defects in mismatch repair (MMR) that are associated with Lynch syndrome.

In addition to combating DNA damage from endogenous and exogeneous agents, cells must also combat replication errors. DNA replication is carried out by high-fidelity polymerases (proteins that synthesize new DNA strands) to ensure genomic integrity. High-fidelity polymerases have low error rates due to their proofreading capabilities. After a nucleotide is inserted, their proofreading domain validates that the correct nucleotide was inserted. If not, the polymerase can remove the incorrect nucleotide and replace it. During replication, the two parental strands are separated and copied to produce new daughter strands. Even with high-fidelity polymerases, an error occurs once every 104 – 105 nucleotides inserted, an error rate which may seem remarkably small but adds up to more than 100,000 errors every replication. These errors can be nucleotide mismatches, as well as small insertions and deletions (indels) that arise from “slippage” of the polymerase. Imagine getting distracted while reading a book and trying to find where you last read. Depending on where you start reading again, you may reread or miss a section. A similar conundrum occurs with replicative polymerases and can lead to the problematic loss or gain of DNA.

Mismatch repair to the rescue

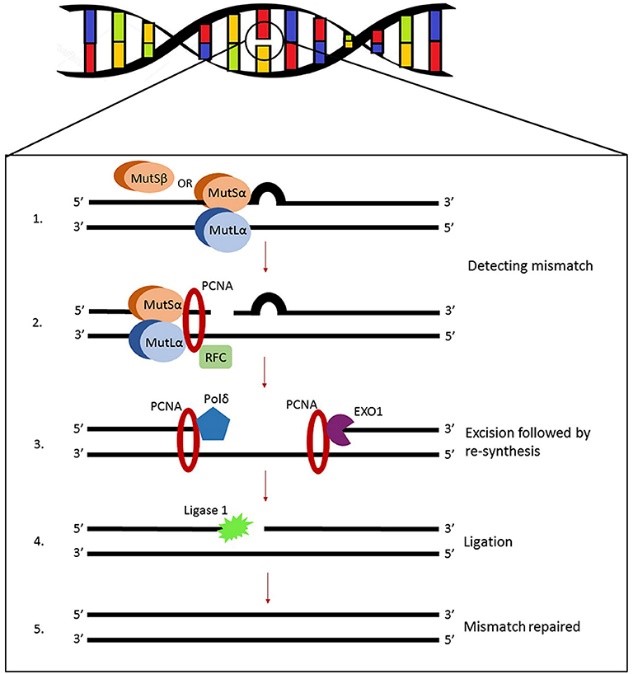

To combat the thousands of replication errors, MMR is activated to detect base pair mismatches and indels. MMR is robust and can also repair certain types of DNA damage. Mismatches and small indels are recognized by a protein called MutSa, while larger indels are recognized by MutSb. MutSa and MutSb are heterodimers, meaning they’re formed by two different polypeptide chains, critical for the initial recognition of errors. Mismatch and indel recognition recruits MutLa and additional proteins to excise (cut out) DNA containing the error, synthesize (re-make, but properly this time) the resulting gap, and ligate (stitch together) the DNA.

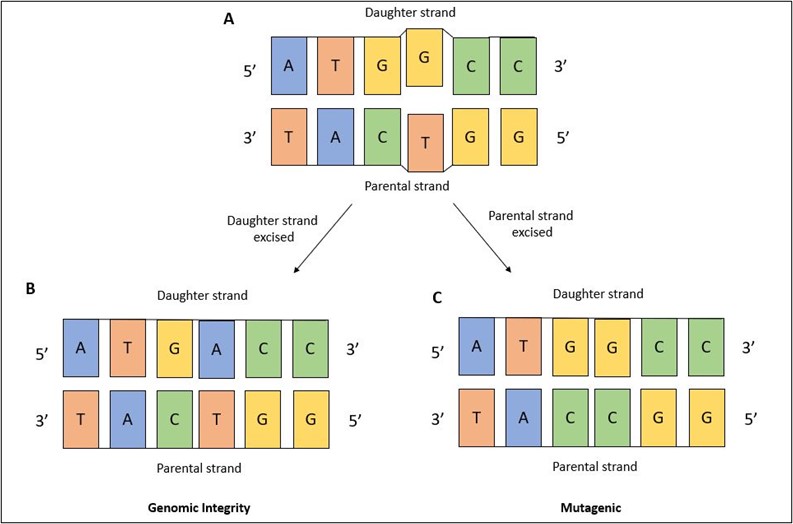

The question remains, if mismatches are formed with undamaged nucleotides – as in, there’s nothing wrong with them structurally, they’re just in the wrong spot – how can MMR decipher which nucleotide to remove? This is an important question because MMR needs to accurately identify the daughter strand that contains the incorrect nucleotide. If MMR were to accidently remove the nucleotide from the parental strand – which is the correct nucleotide – then the DNA becomes altered (Figure 3). It’s not entirely clear how MMR differentiates the parental and daughter strands from one another – that remains an open question in the DNA repair field.

Lynch syndrome: why you should care about it

Lynch syndrome, also referred to as hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer, arises due to defects in MMR. While Lynch syndrome is most commonly associated with colorectal cancer, affected individuals also have an increased risk for endometrial, gastric, and ovarian cancers, among others. The risk for cancer in these individuals is quite high, with some estimates suggesting an 80% lifetime risk of developing colorectal cancer. Lynch syndrome is characterized by several identified mutations in genes called MSH2, MSH6, MLH3, and PMS2. MutSa (MSH2/MSH6) and MutLa (MLH3/PMS2) are proteins critical for the detection and initial processing of mismatches and indels, so mutations in any of these genes can render MMR inoperative. Lynch syndrome is inherited in an autosomal (non-sex chromosome) dominant manner, which means one mutated copy is sufficient to elicit disease. Affected individuals typically possess one functional and one mutated gene copy (MSH2. MSH6, MLH3, or PMS2). If the functional copy acquires a mutation during an individual’s lifetime, then MMR becomes defective and the risk for cancer increases.

Lynch syndrome is the most common hereditary cause of colorectal cancer. If you have a family history of colorectal cancer, talk with your doctor to see if screening is the right choice for you. An 80% lifetime risk of colorectal cancer may seem unsettling, but preventative measures, such as routine colonoscopies, can be started early on for individuals that test positive for Lynch syndrome or any of the other hereditary conditions.

TL;DR

- DNA damages and replication errors need repaired to preserve genomic integrity.

- Replication errors, such as mismatches and insertions/deletions, are repaired by mismatch repair.

- Mismatch repair deficiency is linked to Lynch syndrome, a hereditary form of colorectal cancer.