By Mariam Melkumyan

What are those star-shaped cells doing in our brains?

Astrocytes are rightly named for their stellate shape, and in my opinion, they are the star of the show when it comes to the functioning of the brain. Astrocytes are important for the blood-brain barrier, for giving support to neurons by supplying the building blocks for neurotransmission, and for clearing neurotransmitters from the synapse.

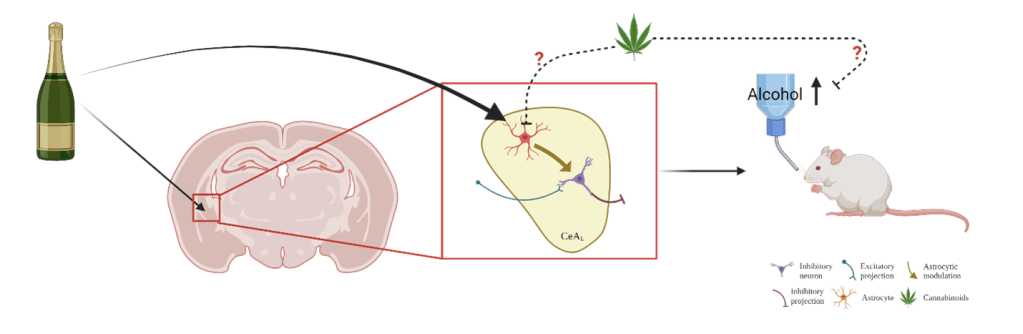

My dissertation focused on the role of the neuroimmune system, mainly astrocytes, on alcohol use and alcohol-induced changes in the brain. Specifically, I focused on the central amygdala, a brain region that is responsible for fear and anxiety and implicated in alcohol use disorder (AUD). AUD is a medical condition affecting millions of individuals in the US annually, characterized by loss of control over alcohol use and impaired ability to stop or control alcohol drinking despite negative social, occupational, and health consequences. The goal of my dissertation was trifold:

- I wanted to see what the effect of alcohol is on central amygdala neurotransmission and how astrocytes and microglia, the resident immune cells of the brain, modulate this effect.

- I wanted to test whether modulating central amygdala astrocytes would lead to changes in alcohol drinking behavior in mice.

- Since cannabinoids are being used to treat anxiety, I wanted to know whether cannabinoids can help reduce alcohol withdrawal-induced anxiety and neuroinflammation.

1. Alcohol’s effect on central amygdala excitatory transmission is mediated by astrocytes.

To understand this part of my research, we need a crash course on whole-cell patch clamp electrophysiology (Figure 1). Whole-cell patch clamp electrophysiology is a technique where a neuron is “poked” with a glass pipette that contains fluid mimicking the internal environment of the neuron. We fuse the glass pipette with the membrane of the neuron and burst through the membrane using suction. This opening of the membrane leads to the pipette and the neuron becoming one entity, allowing us to read the electrical currents happening in the cell.

Using this technique, we can test excitatory and inhibitory activity of the cell, and measure whether a drug application makes the cell more or less excited. In my studies, I used brain slices containing the central amygdala and used patch-clamp electrophysiology to assess the effect of alcohol on central amygdala cells’ electrical activity. I found that the application of alcohol led the cells to be more excited. However, my ultimate goal was to assess if neuroimmune cells contribute to this effect of alcohol on central amygdala cells. Therefore, I pretreated central amygdala containing brain slices with an astrocyte inhibitor, fluorocitrate, or a microglia inhibitor, minocycline. Fluorocitrate acts on the mitochondria of astrocytes, reducing their metabolism and thereby inhibiting their activity. However, it is important to note that fluorocitrate can also inhibit the mitochondrial activity of neurons if left on the slice for too long, so slices were only exposed briefly to target astrocytes. The mechanism of action of minocycline on microglia is less understood, with recent studies suggesting that minocycline changes the microglia from a pro-inflammatory to an anti-inflammatory state.

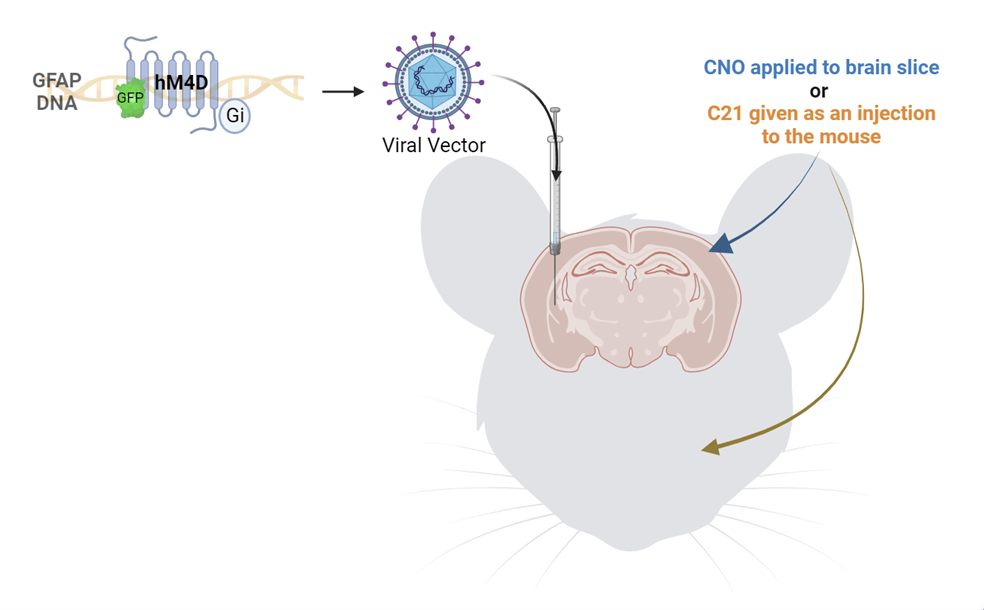

When I repeated the recordings, pretreating the slices with astrocyte inhibitor before applying alcohol, I found that there was no increase in the excitatory activity of the cells in response to alcohol. In contrast, there was still an increase in the activity of the cells treated with the microglia inhibitor. This finding led us to believe that alcohol’s excitatory effect on central amygdala cells was mediated by astrocytes, not microglia. To be rigorous, we wanted to inhibit astrocytes in a different way and see if we could replicate these results. We used a chemogenetic method involving a viral injection of a designer receptor that is exclusively activated by a designer drug (DREADD), in this case clozapine-N-oxide (CNO) (Figure 2). This receptor was an inhibitory receptor specific to astrocytes. Therefore, when this receptor was activated by CNO, astrocytes were inhibited. So, we repeated our previous experiment, but instead of pretreating the slices with fluorocitrate, we pretreated the slices with CNO, effectively inhibiting the astrocytes. When we applied alcohol to the slices, we found the exact same result as before, confirming that astrocytes are needed for alcohol to increase excitatory activity in central amygdala cells. This was an exciting finding, but what does this finding mean in terms of behavior?

2. Inhibition of astrocytes on alcohol drinking days decreases alcohol consumption.

To test the effect of central amygdala astrocytic inhibition on alcohol consumption, we microinjected mice with the same DREADDs and activated the designer receptor with a different compound, called compound 21 (C21). The reason we used C21 instead of CNO is that CNO can have many off target effects when given to the whole organism, but C21 does not have these off target effects. To test the effects of inhibiting astrocytes on behavior, we induced binge-like alcohol drinking in mice using a binge eating/binge drinking paradigm that was developed in our lab.. We gave mice high fat diet (HFD) and water on Mondays for 24 hours, and on Tuesday through Friday we gave the mice normal rodent chow throughout the day and a “two bottle choice” of alcohol or water for 4 hours each day. After the 4 hours, the alcohol was removed, and mice only had access to water. Half an hour before the first alcohol drinking session of the week, we injected mice with C21 to activate the designer receptors, effectively inhibiting central amygdala astrocytes. We then gave the mice the alcohol and water two bottle choice. We found that astrocyte inhibition prior to the first alcohol drinking session of each week led to reduced alcohol consumption. From our findings thus far, we know that astrocytes are necessary for alcohol’s effects on excitatory transmission in the central amygdala and that they are necessary for the escalation of alcohol drinking in this paradigm. We also wanted to assess how alcohol directly affects astrocytes.

To do this, we performed calcium imaging to measure the effect of alcohol on astrocytic calcium activity. Even though the literature is unclear on what changes in astrocyte calcium activity truly mean, we do know that in neurons, increased calcium activity means increased excitation. When we applied alcohol to our central amygdala containing slices, we found increased astrocytic calcium activity in response to alcohol. We also found that the central amygdala brain slices of mice with prior exposure to HFD and alcohol had a sensitized increase in calcium activity in response to alcohol application. Taken together, the findings from these two studies show that alcohol increases calcium activity of astrocytes in the central amygdala, leading to increased excitatory activity in neurons of the central amygdala, consequently increasing alcohol consumption. It is important to remember that there are a lot of other factors that play a role in alcohol consumption, and this one circuit and one cell type are not the single answer for curing alcohol use disorder. However, our findings bring us closer to new potential therapeutics for alcohol use.

3. Cannabinoids may normalize the alcohol withdrawal-induced reduction in neuroimmune activity in the central amygdala.

We know that cannabinoids are currently being used as a treatment for anxiety. We also know that alcohol withdrawal leads to increased anxiety, which can lead to individuals wanting to consume more alcohol to alleviate the anxiety symptoms, creating a vicious cycle. Therefore, our goal was to test whether we can use cannabinoids to reduce anxiety and alcohol-induced changes in neuroimmune activity. We found mixed results on cannabinoids’ effects on alcohol withdrawal-induced anxiety, with most cannabinoids having no effect on this type of anxiety. It is worth noting that our effect size for increased anxiety in these mice was very low, pointing to the need for using a better model to study alcohol withdrawal-induced anxiety. Interestingly, when we explored the neuroimmune activity in the brains of these mice, we found reduced astrocytic activity and microglial density in the central amygdala in mice in 4-hour withdrawal. This finding was unexpected, as alcohol is usually shown to increase neuroinflammation in the brain. The finding was also surprising as we did not find any differences in neuroimmune activity at 24 hours of withdrawal. However, the cannabinoids seemed to mostly normalize this reduced neuroimmune activity at 4 hours, pointing to potential therapeutic effects of the cannabinoids.

Overall, this dissertation highlighted the important role of central amygdala astrocytes in alcohol’s effects on neurotransmission, alcohol consumption, and alcohol withdrawal-induced anxiety (Figure 3). We hope that future research will explore the role of astrocytes in alcohol use to lead to better therapeutics for treating alcohol use disorders.

TL;DR

- Astrocytes are necessary for alcohol to increase the activity in the amygdala of the brain.

- Alcohol increases calcium activity which drives increased alcohol consumption.

- Astrocytes in the amygdala play an important role in the alcohol’s effect on neurotransmission, alcohol consumption, and alcohol withdrawal-induced anxiety.