By Coryn Hoffman

The skin, or the epidermis, is the largest organ in your body, but have you ever thought about the structural components that allow your skin to stay intact? Cell-cell junctions are critical for maintaining the integrity of the epidermis, which protects your body from dehydration and external elements such as infection, physical stress, and extreme temperatures. Desmosomes are one type of cell junction that connect the cytoskeleton to sites of cell-cell contact, providing the cell with structure and support much like a scaffold does at a construction site1 (Figure 1). Desmosomes maintain adhesion between cells, helping to keep certain tissues from breaking apart. Maintaining this adhesion is especially important in tissues like the skin and the heart, which experience significant mechanical stresses. Think about the stretching and compression of the skin during everyday activities and the constant beating of the heart2.

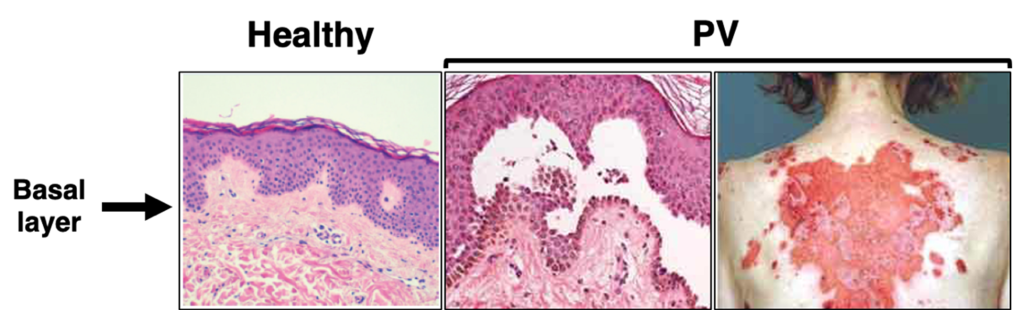

Due to their role in cell-cell adhesion and structural support, disruption of desmosomes leads to tissue fragility, and is the hallmark of various skin diseases like pemphigus vulgaris (PV). PV is an autoimmune skin blistering disease where patients produce antibodies that attack proteins in their own body, known as autoantibodies (IgG). In the case of PV, patients produce antibodies that attack desmoglein 3 (Dsg3), a protein necessary for desmosomal adhesion3. When PV patient IgG attacks Dsg3, it causes desmosome disruption and loss of adhesion between keratinocytes (a type of skin cell) in the deepest layer of the epidermis, termed the basal layer3. Clinically, PV patients present with painful blisters and erosions on the skin and mucosal surfaces like the mouth4,5 (Figure 2). While it is well-established that these autoantibodies against Dsg3 are the cause of PV, researchers still do not fully understand the cellular signaling mechanisms that lead to loss of cell-cell adhesion in this disease4.

Without treatment, PV can lead to severe pain and render patients vulnerable to additional infections. In particular, PV patients have a higher risk of mortality from systemic and respiratory tract infections, cardiovascular disease, and peptic ulcer disease8. The gold standard treatment for PV is systemic corticosteroids, which are drugs that suppress the immune system9. However, patients undergoing such immunosuppressive treatments carry serious risk of infections by other pathogens, which is especially problematic in the event of a global pandemic. With the emergence of COVID-19, the opportunistic infection risk for patients on immunosuppressive treatments became higher than ever, presenting a critical need for more targeted therapies for PV. In addition to improving patient outcomes, learning about rare diseases like PV helps us better understand fundamental biology, particularly how desmosomes dynamics are regulated.

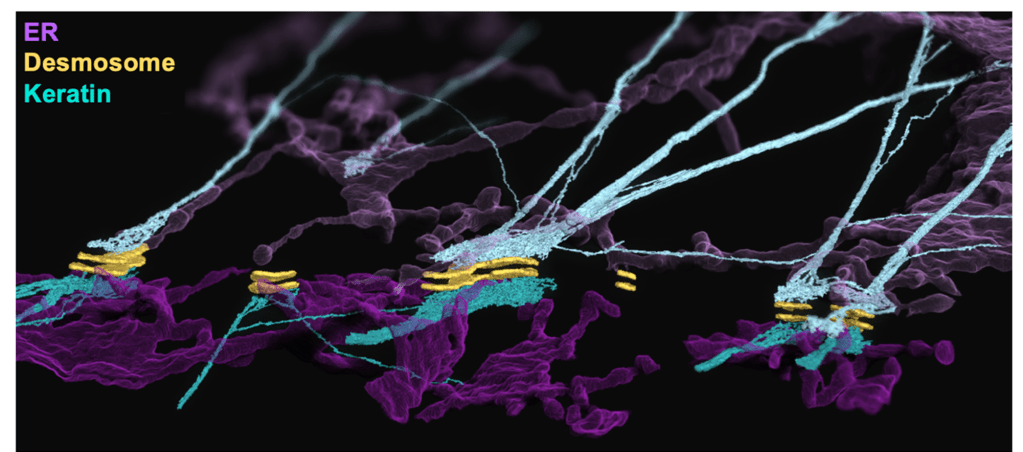

Studies from our lab using advanced imaging techniques such as focus ion beam scanning electron microscopy have demonstrated a previously unknown association between desmosomes and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)10 (Figure 3). The ER is a dynamic network that makes contacts with other cell membranes and is known to regulate stress responses, calcium signaling, and lipid transfer11. Our findings have established a clear structural relationship between desmosomes and the ER, but we have yet to establish the functional relationship of this multi-organelle complex and its potential contributions to PV pathogenesis10.

We hypothesize that the ER is capable of sensing changes in cell adhesion strength at the desmosome, where it can initiate cellular stress signals in response to mechanical disruption such as desmosome attack by PV IgG. One of these cellular stress signals is known as the “ER stress response,” which can be induced by various cellular conditions including defective protein secretion, glucose starvation, calcium flux across the ER membrane, hypoxia, and accumulation of unfolded proteins12. In an attempt to restore normal ER function, the cell activates ER stress pathways that reduce protein synthesis, activate expression of folding or degradation mechanisms, or if the damage is irreversible, these pathways can also activate apoptosis, commonly known as “programmed cell death”.

In my research, I found that when keratinocytes are treated with PV IgG from different patients, there is an increase in various ER stress markers, which are molecules that become actively produced during ER stress10. Additional preliminary studies from our lab show that drugs that inhibit ER stress appear to prevent PV IgG-induced desmosome disruption and loss of cell-cell adhesion. In other words, preventing ER stress is protective against the pathogenic effects of PV IgG. These findings suggest that ER stress pathways have the potential to be therapeutically targeted for the treatment of PV. In fact, ER stress has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of alcoholic pancreatitis, Darier’s disease (another desmosome disorder), and has been linked to an increased risk of various metabolic diseases such as diabetes, obesity and dyslipidemia10,13,14. Thus, there are lots of diseases in addition to PV that could benefit from the clinical development of ER stress inhibitors. Not only do our novel findings expand our current knowledge about desmosome and ER biology, they also lay the foundation necessary for the identification of novel therapeutic targets that will ultimately improve patient outcomes.

TL:DR

- Pemphigus vulgaris (PV) is a potentially fatal skin blistering disease

- Immunosuppressive PV treatments increase risk of infection

- Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) associates with desmosomes in a novel multi-organelle complex

- ER stress appears to be a potential therapeutically targetable pathway for PV patients

References

1. Stahley SN, Kowalczyk AP. Desmosomes in acquired disease. Cell Tissue Res. 2015;360(3):439-56. Epub 2015/03/22. doi: 10.1007/s00441-015-2155-2. PubMed PMID: 25795143; PMCID: PMC4456195.

2. Saito M, Stahley SN, Caughman CY, Mao X, Tucker DK, Payne AS, Amagai M, Kowalczyk AP. Signaling Dependent and Independent Mechanisms in Pemphigus Vulgaris Blister Formation. PLOS ONE. 2012;7(12):e50696. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050696.

3. Jennings JM, Tucker DK, Kottke MD, Saito M, Delva E, Hanakawa Y, Amagai M, Kowalczyk AP. Desmosome disassembly in response to pemphigus vulgaris IgG occurs in distinct phases and can be reversed by expression of exogenous Dsg3. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131(3):706-18. Epub 2010/12/17. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.389. PubMed PMID: 21160493; PMCID: PMC3235416.

4. Stahley SN, Warren MF, Feldman RJ, Swerlick RA, Mattheyses AL, Kowalczyk AP. Super-Resolution Microscopy Reveals Altered Desmosomal Protein Organization in Tissue from Patients with Pemphigus Vulgaris. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2016;136(1):59-66. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/JID.2015.353.

5. Kridin K, Schmidt E. Epidemiology of Pemphigus. JID Innovations. 2021;1(1):100004. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xjidi.2021.100004.

6. Stanley JR, Amagai M. Pemphigus, Bullous Impetigo, and the Staphylococcal Scalded-Skin Syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355(17):1800-10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra061111.

7. Kasperkiewicz M, Ellebrecht CT, Takahashi H, Yamagami J, Zillikens D, Payne AS, Amagai M. Pemphigus. Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2017;3(1):17026. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.26.

8. Huang Y-H, Kuo C-F, Chen Y-H, Yang Y-W. Incidence, Mortality, and Causes of Death of Patients with Pemphigus in Taiwan: A Nationwide Population-Based Study. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2012;132(1):92-7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/jid.2011.249.

9. Calkins CC, Setzer SV, Jennings JM, Summers S, Tsunoda K, Amagai M, Kowalczyk AP. Desmoglein Endocytosis and Desmosome Disassembly Are Coordinated Responses to Pemphigus Autoantibodies *. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281(11):7623-34. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512447200.

10. Bharathan NK, Giang W, Hoffman CL, Aaron JS, Khuon S, Chew T-L, Preibisch S, Trautman ET, Heinrich L, Bogovic J, Bennett D, Ackerman D, Park W, Petruncio A, Weigel AV, Saalfeld S, Wayne Vogl A, Stahley SN, Kowalczyk AP, Team CP. Architecture and dynamics of a desmosome–endoplasmic reticulum complex. Nature Cell Biology. 2023. doi: 10.1038/s41556-023-01154-4.

11. Schwarz, D. S. & Blower, M. D. The endoplasmic reticulum: structure, function and response to cellular signaling. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 73, 79–94 (2016).

12. Høyer-Hansen M, Jäättelä M. Connecting endoplasmic reticulum stress to autophagy by unfolded protein response and calcium. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14(9):1576-82. Epub 2007/07/07. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402200. PubMed PMID: 17612585.

13. Li H, Wen W, Luo J. Targeting Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress as an Effective Treatment for Alcoholic Pancreatitis. Biomedicines. 2022; 10(1):108. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10010108

14. Sarvani C, Sireesh D, Ramkumar KM. Unraveling the role of ER stress inhibitors in the context of metabolic diseases. Pharmacol Res. 2017 May;119:412-421. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.02.018. Epub 2017 Feb 22. PMID: 28237513.