By Paige Elizabeth Bond

Don’t worry, scientists haven’t brought back the dinosaurs… yet. Instead, researchers are working on developing new ways to understand reproduction through a genetically engineered fruit fly. Before getting into the topic of genetic engineering, we should start with the basics of reproduction. Reproduction starts with the creation of gametes, which are eggs and sperm that have half of the genetic material, organized into chromosomes, compared to normal cells. The fusion of these gametes results in a zygote that has the same genome, or number of chromosomes, as an adult of that species. For example, human gametes are haploid and have 23 chromosomes, while zygotes are diploid and have 46. The zygote undergoes many cell divisions to differentiate into the many cell types necessary to create a functioning organism, but the genetic material in these cells stays the same. This fusion of gametes from two individuals of a species explains sexual reproduction, but asexual reproduction is similar. For animals, asexual reproduction requires the fusion of female egg cells from only one individual to produce a zygote. Parthenogenesis is a type of asexual reproduction that follows this mechanism. Different variations of parthenogenesis in different species can occur, with either haploid or diploid offspring as a result (Figure 1). Although this form of reproduction leads to less genetic variation, parthenogenesis gives these species an evolutionary advantage when mates are hard to come by. The offspring produced by parthenogenesis are also not clones of the mother, creating a slight survival advantage5. Species that have facultative parthenogenesis can reproduce either sexually or asexually. A more detailed description of sexual and asexual reproduction is shown in Figure 1.

Mechanisms of reproduction are as diverse as the number of species on this planet, making them difficult to model. Usually in the laboratory, simple organisms that reproduce frequently, such as fruit flies, are used to understand reproduction and genetic inheritance. D. melanogaster, the most used laboratory fruit fly, cannot naturally reproduce through parthenogenesis. As D. melanogaster is commonly used to study sexual reproduction and inheritance, its inability to reproduce utilizing parthenogenesis is generally good news for genetic crosses. Conversely, scientists wanted to induce this phenomenon to create a better model to study this form of asexual reproduction. By understanding the genes involved with parthenogenesis, scientists are hoping to understand how this phenomenon evolved and study its advantages and disadvantages compared to sexual reproduction 4. The fruit fly makes a better model for asexual reproduction than the mouse because mice undergo genomic imprinting, which causes some genes to be silenced, while flies do not5. Also, a fly model can better illustrate the many agricultural pests that are able to reproduce via parthenogenesis. One example of this is Tuta absoluta, a species of moth that damages tomato crops. A common strategy to manage an infestation of this moth includes a spray that disrupts mating6. For obvious reasons, this is less effective when the insects can still reproduce via parthenogenesis. Therefore, studying how to induce parthenogenesis in the laboratory can help scientists find better ways to manage pest infestations to protect agriculture.

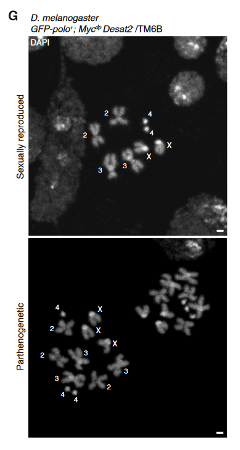

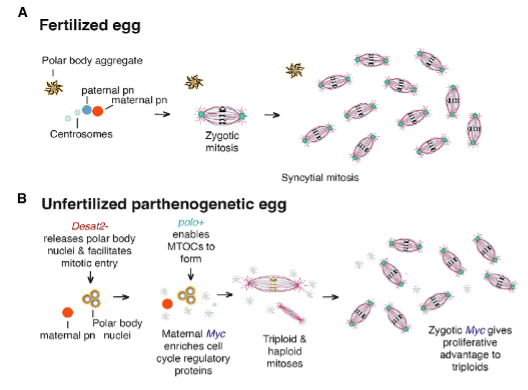

To produce a parthenogenic strain of D. melanogaster, researchers first turned to three different strains of the related speciesD. mercatorum: one that reproduces sexually, one that reproduces through parthenogenesis, and one that can use both through facultative parthenogenesis. Analysis of the eggs of these three strains indicated multiple pathways that were upregulated in the parthenogenetic flies. These pathways indicated genes that may be important for the maturation of the zygote if no genetic material from sperm is available, as would be the case in parthenogenesis. Researchers then did a CRISPR/RNAi screen to change gene expression of 44 significant genes and 5 control genes identified in the comparison, utilizing homologs in D. melanogaster. Homologous genes are optimal for comparison because they share similar genetic sequences and functions, relating back to the shared evolutionary ancestor of the two closely related species. Knocking out or down only one of the genes resulted in high death rate among the flies, even in terms of the control genes. Researchers therefore moved onto pairwise combination of 16 of the most differently expressed genes. This combination resulted in parthenogenic females whose offspring did not mature to adulthood. To increase mitosis of the early zygote, the researchers added a growth-promoting gene onto the third chromosome of the flies. This insertion resulted in 11.4% facultative parthenogenesis of the flies, with offspring surviving until adulthood. The genome of the offspring produced via parthenogenesis had a greater number of chromosomes, but no obvious physical abnormalities (Figure 2). These offspring were also able to reproduce via parthenogenesis, indicating that the parthenogenesis was heritable.

Looking at the function of the mutations in the parthenogenic flies gave some insight to the necessary biological conditions for facultative parthenogenesis. Manipulation of the Desat2 and polo genes promotes structural integrity of the zygote throughout cell divisions. The Myc gene promotes more cell division, giving the early zygote a necessary growth advantage for survival. These three genes that were either mutated or inserted into D. melanogaster were sufficient for the flies to utilize facultative parthenogenesis. The function of these genes during the parthenogenetic process is not fully understood, and more research needs to be conducted. Further research into parthenogenesis would lead to better understanding of its natural development; however, the basis of this research produced a current model of parthenogenesis (Figure 3). This model lays the foundation for future work in understanding the process of parthenogenesis.

Since even before the dinosaurs, diverse forms of life have been evolving to create the vast number of species we see today. It would make sense that the processes involved in reproduction would also be incredibly diverse and continuously evolving. With the creation of a genetically engineered fly model, future mechanistic study of the evolution of sexual reproduction versus parthenogenesis can be conducted. The parthenogenetic model fly could also provide insight into the environmental and intrinsic factors that can trigger this form of asexual reproduction. Information about environmental triggers for parthenogenesis can be used to create better pest management programs, protecting agriculture against pests such as the moth T. absoluta mentioned above.

TL:DR

- Scientists have created a D. melanogaster fruit fly strain that exhibits sporadic facultative parthenogenesis, a form of asexual reproduction.

- This model can be used for further study of the evolution of parthenogenesis and help fight agricultural pests that reproduce via this mechanism.

References

- Jeff Goldblum, Richard Attenborough, Laura Dern and Sam Neill in “Jurassic Park.”Universal Pictures / via Getty Images.

- Sperling, A. L.; Fabian, D. K.; Garrison, E.; Glover, D. M. A Genetic Basis for Facultative Parthenogenesis in Drosophila. Current Biology 2023, S0960982223009132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2023.07.006.

- Britannica, T. E. of E. Parthenogenesis. Encyclopedia Britannica 2023.

- Oza, A. ‘Virgin Birth’ Genetically Engineered into Female Animals for the First Time. Nature 2023, d41586-023-02404-z. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-02404-z.

- Vrana, P. B. Genomic Imprinting as a Mechanism of Reproductive Isolation in Mammals. J Mammal 2007, 88 (1), 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1644/06-MAMM-S-013R1.1.

- Grant, C.; Jacobson, R.; Bass, C. Parthenogenesis in UK Field Populations of the Tomato Leaf Miner, Tuta Absoluta , Exposed to the Mating Disruptor Isonet T. Pest Manag Sci 2021, 77 (7), 3445–3449. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.6394.

Pingback: “You (Don’t) Got Male”: Parthenogenesis and its Applications in Biomedical Research | Lions Talk Science