By Sarah Latario

The bunch of bananas you bought at the grocery store this week are genetically identical to the ones you ate last month. The bananas imported into the United States and sold in most stores are all clones from a single banana tree, which originated in south China in 1826. This variety, called Cavendish, is sterile and look very little like the other 1,000+ varieties of bananas that exist. The Cavendish are a genetic outlier with three copies of each chromosome, while wild bananas only have two. This unique genetic composition makes these bananas perfect for growing at scale, as they cannot be accidentally cross pollinated and “tainted” by the genes from wild varieties. Their identical genetics also makes them a very reliable crop. Farmers know how the Cavendish will respond to pesticides, how long they take to ripen, how much water they need, and how many bananas each plant will yield. This knowledge allows for the utilization of a standard farming system that yields a uniform, reliable, and high-profit crop across multiple fields, countries, and continents. The Cavendish clones almost single-handedly make up the entire banana export industry, with 55 million tons being shipped around the world every year, propping up a 25-billion-dollar industry.

Cavendish were not always the dominant banana variety. Before them, the Gros Michel banana reigned supreme with a creamier, sweeter taste, and thicker peel which made transport easy. Bananas first came to the United State in the 1800s, brought by ship captains returning from the Caribbean and sold in ports from New Orleans to New England. By the late 1800s, fruit companies took over the trade and created large plantations that focused on growing only the Gros Michel, due to its superior quality and ease of shipping. The Cavendish variety existed during this time but was considered second rate. However, Cavendish progressively rose to prominence between the 1920s and 1960s thanks to a strain of Fusarium fungus called Tropical Race 1 (TR1). This fungus infected Gros Michel trees, killing off field after field of bananas across Latin America and sparking the beginning of the Cavendish dynasty. Naturally resistant to TR1 infection, Cavendish trees rose from the ashes of the Gros Michel. As Gros Michel trees failed, plantations were replanted with Cavendish, and by 1965 the Cavendish had fully replaced the Gros Michel banana in US markets.

Although the Cavendish banana has reigned supreme for over half a century, it is facing the same downfall as its predecessor. The very thing that made its success is now threatening to cause its destruction. A new Fusarium fungus, Tropical Race 4 (TR4), has arisen and the Cavendish is no longer resistant to the fungus. TR4 lives in the soil, is resistant to fungicides, and infects plants through their roots. It grows up into the center of the tree and cuts off its ability to absorb water and nutrients, essentially starving the tree. Since the infection spreads outward from the center of the tree, there are often few unique signs of sickness until the tree suddenly collapses under the weight of itself, exposing its diseased, hollowed-out centers.

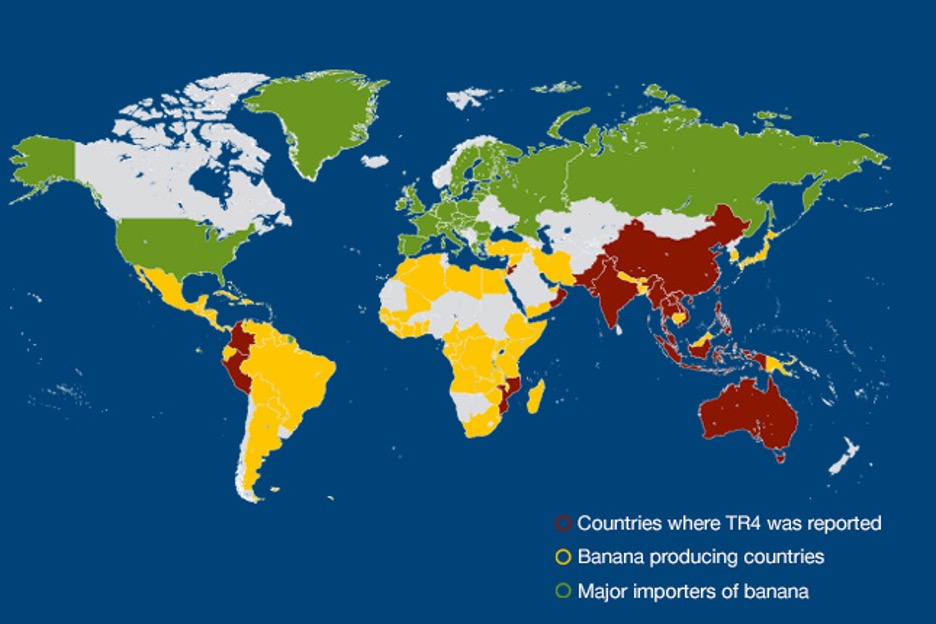

TR4 infections were first identified in Taiwan in the 1960s and quickly spread, becoming a much more serious issue than expected (Figure 1). By the 1990s, TR4 infections jumped continents, appearing in East Africa and Australia, and in 2019 were found in Latin America. The fungus can linger in the soil for 30 years, ruining plantation land and preventing new trees from being planted to replace the ones lost to infection. Although the fact that Cavendish bananas are all clones seemed like a blessing to early farmers, it has now become a curse. Once one tree is infected with TR4, it easily spreads through the entire plantation because all trees are equally susceptible to infection due to their identical genetics. Because of this unique susceptibility, and how widely TR4 has already spread, researchers believe Cavendish bananas could become extinct in the next several decades.

To battle this impending extinction, researchers around the world are utilizing diverse genetic engineering approaches to create TR4 resistant Cavendish bananas.1 A team in Australia has isolated a gene from wild bananas and inserted it into the Cavendish genome. These plants are able to grow in TR4+ soil without becoming infected (Figure 2). Due to various regulations across Australia, the US and the EU, these bananas have yet to be approved to be grown and sold in markets.

Introducing any new genetic material raises a red flag for regulators, but removing and editing genes currently in the genome is less frowned upon. Therefore, these same regulations are more forgiving of CRISPR edited organisms. CRISPR utilizes a mechanism that recognizes specific sequences of DNA and cuts them out. This cutting process is very precise and can be used on many different genes across numerous cell types. The acceptance of this CRISPR technology has sparked new biotech companies to begin using this approach to engineer a more robust Cavendish banana using stem cells. These cells can be grown to give rise to other types of cells that eventually develop into the banana tree.

Embryogenic Cavendish banana stem cells have been cultured and edited to grow into full-sized plants with fruit that has a heightened immune system and lacks the genes required for TR4 infection. Other modifications are also in the works that will yield bananas that are less susceptible to browning and slower to ripen, increasing the number that survive shipping. However, CRISPR does not work in every cell it is introduced to. The hurdle lies in selecting for the correctly modified stem cells that can then be used to create new banana tree varieties. The genes normally inserted to help researchers are considered extraneous DNA but are crucial for identifying properly transformed cells to be isolated and grown into new banana trees.

While many researchers continue to invest in genetically modifying the Cavendish, others believe that the banana market should shift to selling a wild variety that already exists and is naturally resistant to TR4. A new banana may take the market in the same way that the Cavendish replaced the Gros Michel. Whether we are eating genetically engineered Cavendish bananas or a new wild variety in the coming decades, the banana is a perfect example of how the balance of nature shifts genetics. As human involvement shapes nature, nature responds, often causing genetic drift and the potential loss of genetic diversity.

TL:DR

- Supermarket bananas are clones from Cavendish banana variety.

- Cavendish bananas conquered markets after a fungus killed its predecessor in the mid-1900s.

- A new fungus threatens Cavendish, and farmers must choose whether to embrace genetic engineering or a different wild banana.

References

- Maxman, A. (2019). CRISPR could save bananas from fungus. Nature, 574, 15.

- Dale, J., James, A., Paul, JY. et al. Transgenic Cavendish bananas with resistance to Fusarium wilt tropical race 4. Nat Commun 8, 1496 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01670-6