By Stephanie Baringer, Ph.D.

The following is a synopsis of my Ph.D. thesis that I defended on July 17, 2023, titled Regulation of Brain Iron Acquisition and Misappropriation in Alzheimer’s Disease. Thank you to LTS for the years of opportunity to write about my deep-dive interests and now for the chance to share this summary of my dissertation findings.

The Set Up: Iron is Important

Iron: it’s one half of Tony Stark’s alter-ego, it paints the American Southwest landscape a distinctive ruddy hue, and it’s an essential element to cellular function. Iron is the most abundant transition metal found in the human body, and an essential factor for a number of biological processes, including DNA synthesis, and energy production via mitochondrial respiration, and the transport of oxygen throughout the body1. In addition to these systemic uses of iron, there are specialized processes in the brain that require a ferric-touch. The synthesis of two key factors in brain signal transmission – neurotransmitters used to relay signals between neurons, and myelin, which insulates neurons to quicken signal speed – both rely on iron1.

If iron is so important for brain function, we should all be trying to get as much iron into the brain as possible, right? Wrong.

There is a fine balance of iron that must be maintained. Too little iron prevents cells from producing energy, myelin, and neurotransmitters, and it can lead to cognitive impairment and developmental problems2. On the other hand, too much iron can lead to cellular death. Free iron can damage cellular structures if the iron is not properly bound to transferrin (Tf), the primary iron transport protein1. Over time, excessive accumulation of iron in the brain can lead to neurodegenerative disease such as Alzheimer’s disease2.

If fluctuating iron levels in the brain are such an issue, how does the body control the movement of iron into the brain space? Enter, stage left: the blood-brain barrier.

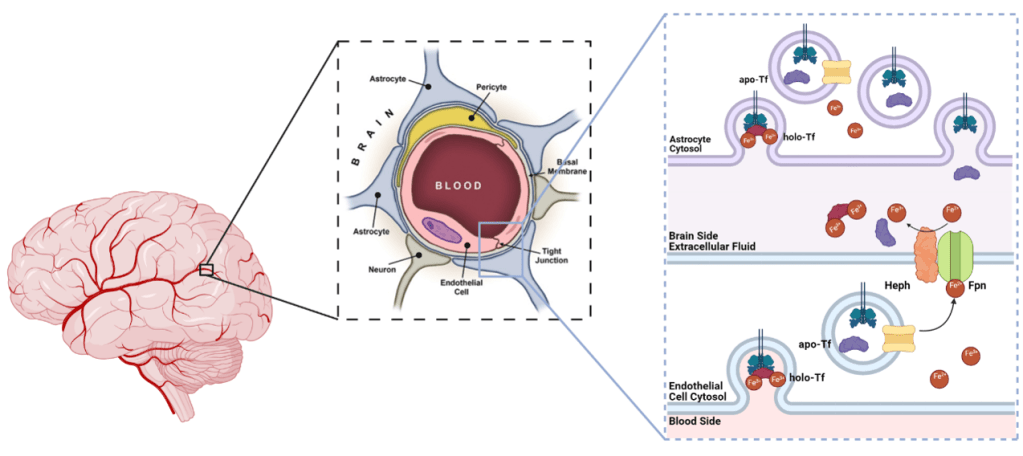

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) is a specialized barrier of cells that encircle blood vessels that permeate throughout brain tissue (Figure 1). The BBB simultaneously prevents entry of foreign compounds and facilitates the movement of essential nutrients into the brain3 (for a deep dive into how therapeutics can cross the BBB, check out my past LTS article here). Of the cell types that comprise the BBB, the endothelial cells directly border the vasculature throughout the brain3, and it is here that the release of iron is regulated to prevent the aforementioned problems with fluctuations in brain iron levels.

The way the brain regulates iron uptake is simple yet elegant (Figure 1). Imagine your house is a neuron and the post office is an endothelial cell (Figure 2). Tf is like your mail carrier, and iron is like letters you need delivered. When cells, such as neurons, need iron, they take up Tf-bound iron, otherwise known as holo-Tf. So in our metaphor, when you (neuron) need mail (iron), the mail carrier with mail in tow (holo-Tf) hand delivers the mail (iron). Once the cell uses that iron, it releases the iron-lacking Tf also known as apo-Tf – which is our mail carrier with no mail. The released apo-Tf can bind more free iron in the extracellular space to start the process all over. In other words, our mail carrier goes to the post office to pick up more mail to deliver to other houses, but only as much as they can carry. If there is an excess of free iron floating in the brain, all of the available Tf will bind to the iron and be holo-Tf. If there is a deficiency of free iron in the brain, the available Tf will remain as apo-Tf.

Now imagine you (neuron) don’t need the mail that the mail carrier is trying to deliver. If the mail carrier cannot deliver the mail, they cannot go back to the post office to get more. And the post office cannot just throw the mail out the door and hope it reaches its destination, so the mail sits at the post office and waits for an available mail carrier. Our lab has shown that when endothelial cells (post office) are exposed to holo-Tf (mail carriers full of mail) on the brain side, the release of iron is suppressed, whereas when the cells are exposed to apo-Tf (mail carriers with empty trucks), the release of iron is stimulated4–6. Thus through brain-side apo- and holo-Tf, cells can signal their iron needs based on their iron consumption and create a feedback loop to modulate iron release from the BBB.

The Gap in Knowledge

Despite the lab already knowing at the start of my Ph.D. research that levels of apo- and holo-Tf control iron release from endothelial cells in a dish, there was a lot we still didn’t know. I set out to answer the following questions in my pursuit of becoming a master of iron biology:

- Do apo- and holo-Tf regulate iron uptake into the brainin living organisms, using mice as a model? Does the sex of the organism or the protein used to deliver the iron impact the regulation?

- How do apo- and holo-Tf affect the release of iron from endothelial cells? Do other iron-release-regulating molecules prevent Tf’s influence?

- Is the process of iron uptake regulation dysfunctional in Alzheimer’s disease, and does this putative dysfunction lead to excessive iron accumulation in the brain?

What I Did and What I Discovered

To address my first question – what does apo- and holo-Tf regulation of iron uptake into the brain look like in an organism? – I had a few considerations. First, human and rodent females have higher rates of iron-consuming processes and iron uptake compared to males7–9. Additionally, while the conventional iron delivery protein is Tf, H-ferritin, an iron storage protein, can also deliver iron to the brain10,11. To determine if changing the levels of apo- and holo-Tf in the brain would impact iron uptake, I infused a steady rate of apo- or holo-Tf directly into the brain of mice. After a few days, I injected the mice under the skin with traceable iron bound to either Tf or H-ferritin. I found that in males, the ratio of apo- to holo-Tf regulates Tf-bound iron uptake, just as it did in previous cell culture experiments. However, in females, this is not the case. In contrast, H-ferritin-bound iron uptake does not differ between males and females and is not influenced by the ratio of apo- to holo-Tf.

Apo- and holo-Tf regulate Tf-bound iron uptake into the brain, but how? Without going into too much detail, the release of iron is facilitated by ferroportin, the only known iron exporter protein, and hephaestin, which stabilizes ferroportin in the cellular membrane. Think of ferroportin as the gate to the post office where mail carriers can pick up mail and hephaestin as the hinges and keypad to open the gate (Figure 2). Hepcidin is a hormone peptide that iron researchers have rallied behind to be the iron release regulator because hepcidin binds to ferroportin, resulting in ferroportin degradation. If ferroportin is a gate, hepcidin is a 2-ton boulder that crushes the gate, renders the gate inoperable, and prevents the mail carriers from collecting more mail. To decipher the mechanism of apo- and holo-Tf’s influence of iron release, I examined the relationship between Tf and these iron-release-regulation proteins using a handful of standard molecular biology techniques. I found that holo-Tf (remember, this is the mail carrier with mail in hand) directly interacts with ferroportin (the post office gate), resulting in ferroportin degradation in a similar pathway as hepcidin-induced degradation. This is as if so many people refused their mail that the mail carriers crowded around the post office gate and damaged it. Disease levels of hepcidin prevent holo-Tf from interacting with ferroportin because hepcidin degrades ferroportin faster than holo-Tf – a 2-ton boulder will damage a gate faster than extra mail carriers. However, physiological levels of hepcidin (think of this as a normal sized rock rather than a boulder) do not impact the interaction between holo-Tf and ferroportin. Apo-Tf directly interacts with hephaestin – remember, the hinges on the ferroportin gate – to facilitate iron release, and this interaction is not interrupted by any amount of hepcidin. It is like the mail carriers typing in the code to open the gate to get more mail to deliver. Whether this condition still facilitates the release of iron (mail) remains to be seen.

Now armed with a newfound understanding of iron regulation in normal conditions, I turned my attention to how the process could be dysregulated in disease. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common neurodegenerative disease, affecting nearly 6.7 million Americans over the age of 65 years. Clinically, it is characterized by cognitive decline and memory loss, and pathologically, it is characterized by amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques, neurofibrillary tau tangles, and excessive iron accumulation in the brain13. Before Aβ and tau tangles spread widely enough to wreak havoc on brain cells, iron starts to accumulate12, suggesting the process of iron uptake becomes dysregulated early in the disease. To test this, I exposed astrocytes, which provide the connection between endothelial cells of the BBB and the rest of the brain, to levels of Aβ consistent with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. I found that in response to Aβ, astrocytes increased their mitochondrial activity and iron uptake. The increased utilization of iron results in elevated levels of apo-Tf in the brain, and thus increased iron release from endothelial cells at the BBB to satisfy the higher iron needs of the astrocytes.

The Key Takeaways

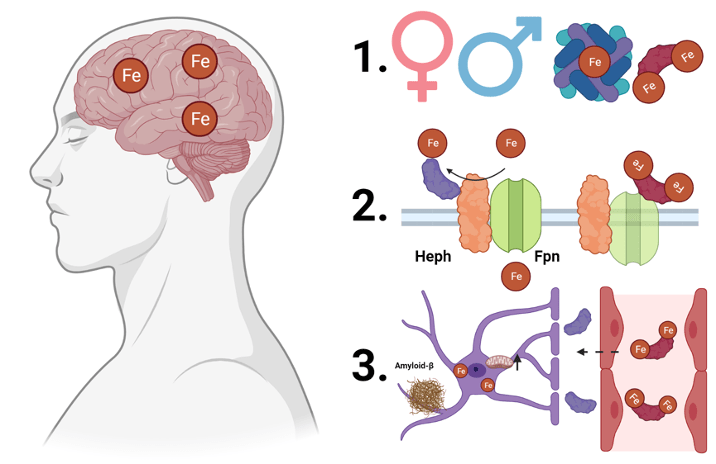

To summarize my three years of dissertation research (Figure 3):

- There are sex differences in the regulation on Tf bound iron uptake into the brain, likely due to different iron needs of male and female brains. H-ferritin bound iron uptake is not regulated by apo- and holo-Tf in the brain, suggesting H-ferritin broadly delivers iron, while Tf delivers iron where it is acutely needed.

- Apo- and holo-Tf differentially interact with proteins to regulate iron release. When hepcidin is present at amounts consistent with disease, it seems to influence iron release more so than holo-Tf, suggesting hepcidin is deployed to act as a metaphorical panic button to stop iron release immediately to prevent further cellular damage.

- Cellular response to pathology of early-stage Alzheimer’s disease causes misappropriation of the regulatory mechanism of iron release, leading to increased iron accumulation.

The Larger Implications

So I uncovered a new cellular mechanism of iron release regulation, big whoop. What does it all mean?

Iron biology has a huge impact on both neurological and peripheral diseases. Because of the fundamental experiments I performed, my findings suggest that apo- and holo-Tf are the iron release regulators throughout the body. Thirty years of research has focused on how hepcidin modulates iron release in disease, but there was a lack of a clear model for how hepcidin would control iron release in non-disease conditions. By accepting our new paradigm of iron regulation, the field can further investigate how apo- and holo-Tf are modulated in disease and figure out whether the overarching mechanism of iron release can be targeted for therapeutic intervention.

On that note, the therapeutic landscape for Alzheimer’s disease has undergone exciting developments over recent years, however, there is still a lack of effective treatments to halt or substantially slow disease progression. The pathological proteins associated with Alzheimer’s disease have received most of the attention from the field, but the influence of iron is important to consider. My findings have shown that early-stage disease levels of Aβ hijack iron release signals, resulting in iron accumulation. Iron has examined in a few Alzheimer’s disease studies and clinical trials (read more in my previous LTS article here), and results suggest that controlling iron accumulation in the brain could be key to successful disease management. How many other diseases could iron regulation play a key role in?

Haven’t Had Your Fill of Iron?

You can find out more by reading my published papers below. If you want to talk more about iron, Alzheimer’s disease, or anything related to drug trafficking into the brain, reach out to me via email at stephaniebaringer@gmail.com. I didn’t get the nickname “Iron Lady” at conferences for nothing!

Baringer SL, Simpson IA, Connor JR. Brain iron acquisition: An overview of homeostatic regulation and disease dysregulation. J Neurochem. 2023 Apr 12. doi: 10.1111/jnc.15819.

Baringer SL, Neely EB, Palsa K, Simpson IA, Connor JR. Regulation of brain iron uptake by apo- and holo-transferrin is dependent on sex and delivery protein. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2022 Jun 10. doi: 10.1186/s12987-022-00345-9.

Baringer SL, Palsa K, Spiegelman VS, Simpson IA, Connor JR. Apo- and holo-transferrin differentially interact with hephaestin and ferroportin in a novel mechanism of cellular iron release regulation. J Biomed Sci. 2023 Jun 6. doi: 10.1186/s12929-023-00934-2.

Baringer SL, Lukacher AS, Palsa K, Kim H, Lippmann ES, Spiegelman VS, Simpson IA, Connor JR. Amyloid-β exposed astrocytes induce iron transport from endothelial cells at the blood-brain barrier by altering the ratio of apo- and holo-transferrin. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2023 May 17. doi: 10.1101/2023.05.15.540795.

TL:DR

- The brain employs neural iron usage to communicate current iron needs to the blood-brain barrier and control iron uptake.

- A thorough understanding of the regulation of cellular iron release is needed to be able to uncover dysfunctions in disease in hopes the process can be exploited for therapies.

References

1. Dev, S. & Babitt, J. L. Overview of Iron Metabolism in Health and Disease. Hemodial Int 21, S6–S20 (2017).

2. Kim, Y. & Connor, J. R. The roles of iron and HFE genotype in neurological diseases. Mol Aspects Med 75, 100867 (2020).

3. Goldstein, G. W. & Betz, A. L. The blood-brain barrier. Sci Am 255, 74–83 (1986).

4. Chiou, B. et al. Endothelial cells are critical regulators of iron transport in a model of the human blood-brain barrier. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 39, 2117–2131 (2019).

5. Simpson, I. A. et al. A novel model for brain iron uptake: introducing the concept of regulation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 35, 48–57 (2015).

6. Duck, K. A., Simpson, I. A. & Connor, J. R. Regulatory mechanisms for iron transport across the blood-brain barrier. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 494, 70–75 (2017).

7. Cerghet, M. et al. Proliferation and death of oligodendrocytes and myelin proteins are differentially regulated in male and female rodents. J Neurosci 26, 1439–1447 (2006).

8. McDermott, J. L., Liu, B. & Dluzent, D. E. Sex Differences and Effects of Estrogen on Dopamine and DOPAC Release from the Striatum of Male and Female CD-1 Mice. Experimental Neurology 125, 306–311 (1994).

9. Munro, C. A. et al. Sex Differences in Striatal Dopamine Release in Healthy Adults. Biological Psychiatry 59, 966–974 (2006).

10. Chiou, B., Neely, E. B., Mcdevitt, D. S., Simpson, I. A. & Connor, J. R. Transferrin and H-ferritin involvement in brain iron acquisition during postnatal development: impact of sex and genotype. Journal of Neurochemistry 152, 381–396 (2020).

11. Chiou, B., Lucassen, E., Sather, M., Kallianpur, A. & Connor, J. Semaphorin4A and H-ferritin utilize Tim-1 on human oligodendrocytes: A novel neuro-immune axis. Glia 66, 1317–1330 (2018).

12. Ayton, S. et al. Regional brain iron associated with deterioration in Alzheimer’s disease: A large cohort study and theoretical significance. Alzheimers Dement (2021) doi:10.1002/alz.12282.

13. Ayton, S. et al. Brain iron is associated with accelerated cognitive decline in people with Alzheimer pathology. Molecular Psychiatry 1–10 (2019) doi:10.1038/s41380-019-0375-7.