By Julia Simpson

Part 1: Snapshot of the Climb

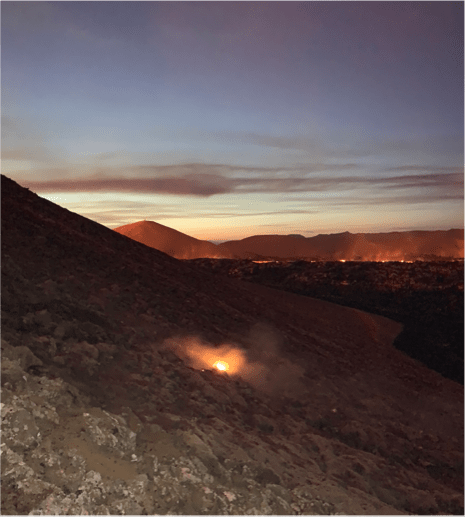

When the golf-ball-sized volcanic bomb struck the ground just ten feet from where Denali Kincaid stood, it set the grass on fire (Figure 1).

“The fire didn’t spread,” Kincaid clarifies. “But it landed right there and I was like, ‘I should not be standing this close to it… so I backtracked a little bit, and went up a different way.”

It was May of 2021, and a new volcano was being born. This eruption of what is now known as the Fagradalsfjall volcano – historically, just a quiet geologic giant on the hilly, green Icelandic landscape – marked the first time a mountain in the Fagradalsfjall region of the Reykjanes Peninsula had woken up and spit fire in six thousand years1. The scale and vivid imagery of the eruption captured global attention. The event was a turning point for Kincaid who, by her mid-twenties, already had a non-linear career trajectory. Having finally found her calling – volcanology – the eruption came as Kincaid was finishing up her Bachelor’s in Geology. Volcanologists worldwide were already beginning to flock to Fagradalsfjall, and Kincaid, too, found herself drawn to it.

“I was just like, ‘oh my god, I have to go,’” Kincaid recalls, recounting the story to me through a Zoom screen, across three thousand miles and a four-hour time difference. At the time of our interview, Kincaid is in Alaska working as a marine geologic contractor; a lab tech at the Alaska Volcano Observatory; and a social media science communicator to over 260,000 followers on TikTok, whom she educates on all things geology.

I’m getting ahead of myself. Back to the actively erupting volcano.

When Kincaid learned of the eruption, she immediately reached out to Dr. Mike Perfit, her research advisor, and asked if he could put her in touch with some Icelandic volcanologists. He connected her with a researcher at the University of Iceland. A few short weeks later, what had started as a far-fetched idea became plane tickets and a plan: she’d observe the University of Iceland team conduct hot lava sampling, then perform her own less hazardous fieldwork independently (Figure 2).

“I feel like there’s still a lot of taboo around just asking for things, around just asking for opportunities – I feel like a lot of people are afraid to do that,” Kincaid says, reflecting on how she wound up climbing an erupting volcano. “But if you don’t ask, you’re never gonna get the opportunity.”

It’s a powerful observation, not only because it’s something all early-career scientists should probably take to heart. The sentiment also offers a window into the mind of a woman who gave herself time to figure out what she wanted and has spent the last three years forging a path to accomplish her goals – not unlike the path she trekked up the Fagradalsfjall volcano, which she embarked on just hours after leaving the Icelandic airport. The route was steep, but she persevered, determined to make it to the designated safe-viewing hilltop, impending nightfall and fire-bombs be damned.

The darkness was near-complete when Kincaid finally made it to the hilltop, the remaining daylight just a sliver of vibrant orange horizon in a deep blue night sky. Before her, lava flowed from the mountain, a rare glimpse of the Earth’s lifeblood churning from a burst vein of its great tectonic body (Figure 3).

“It was the most amazing moment of my life,” Kincaid says. “I start[ed] giggling… laughing and tearing up.” Standing there, the path of her future was as sure and striking as the flames against the dark. “I was like, ‘yeah, this is what I’m doing,’” she recounts. There’s no one set track towards becoming a volcanologist, and Kincaid’s path was certainly a winding one – but in that moment, she knew she’d finally found her way (Figure 4).

Part 2: The Winding Road

“I started off pre-med, and I know lots of people who loved it and are very passionate about it,” Kincaid tells me, “…but I was not passionate about it. I hated it.” What next, then, for a young woman whose entire family was either in the military or the medical field? Kincaid left school, worked as a bank notary, saved money, and did some self-reflection about what she enjoyed in life.

“I like being outside, and I like the ocean,” Kincaid says. She grew up on an island off of southeastern Alaska, a location she credits with heavily influencing her professional interests today. So, she enrolled in community college classes in earth science and oceanography, and the curriculum introduced her to a concept that captivated her like nothing else had before.

“We learned about mid-ocean ridges (Figure 5)… where two tectonic plates are diverging apart, and in between them magma/lava comes up between the two plates.” Kincaid gestures, mimicking the diverging plates. “There’s volcanism all along mid-ocean ridges. It accounts for something like 60-80% of the world’s volcanism, so the majority of our volcanism is actually on the ocean floor.”

Fascinated and entranced, Kincaid started reading about volcanology and prominent researchers in the field. This is how she learned about renowned submarine volcanologist Dr. Mike Perfit. Emboldened with new purpose, Kincaid decided to apply to the University of Florida, where Dr. Perfit worked, to pursue a Bachelor’s in Geology.

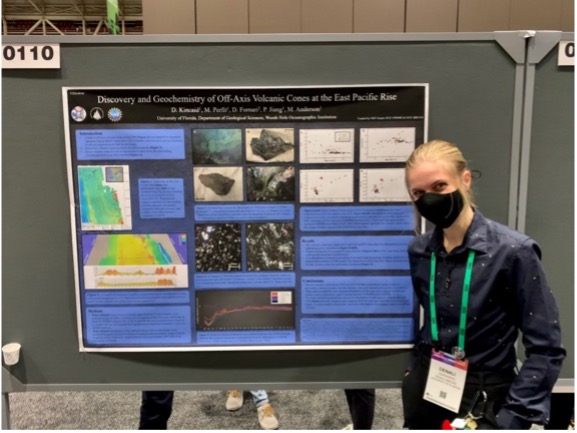

“I wanted him as my advisor,” she says. “I hadn’t talked to him. I just applied to the school, and I was like – I’m just gonna do my best.” Kincaid worked hard, and her academic success eventually led her to be hired as an undergraduate researcher in Dr. Perfit’s lab (Figure 6). After the Fagradalsfjall trip, she planned to use her volcanic samples for her senior thesis, but in the end, a different opportunity arose that she couldn’t pass up.

“[Our colleagues] had a set of samples from… submarine volcanic cones at the East Pacific Rise,” Kincaid explains excitedly. The East Pacific Rise is a tectonic plate boundary deep below the Pacific Ocean. In a poetically full-circle moment, she was able to write her thesis on the geochemical composition of rock formed at the very type of geological formation – mid-ocean ridges – that had sparked her love for geology (Figure 7).

After earning her degree, Kincaid wanted to pursue a PhD in volcanology, but she sought more experience first. “The job that I have at the volcano observatory, that position didn’t exist when I wanted it,” Kincaid says. “There are no volcanology jobs that you can get with just a bachelor’s, and I didn’t want to spend my gap year doing not-volcanology.”

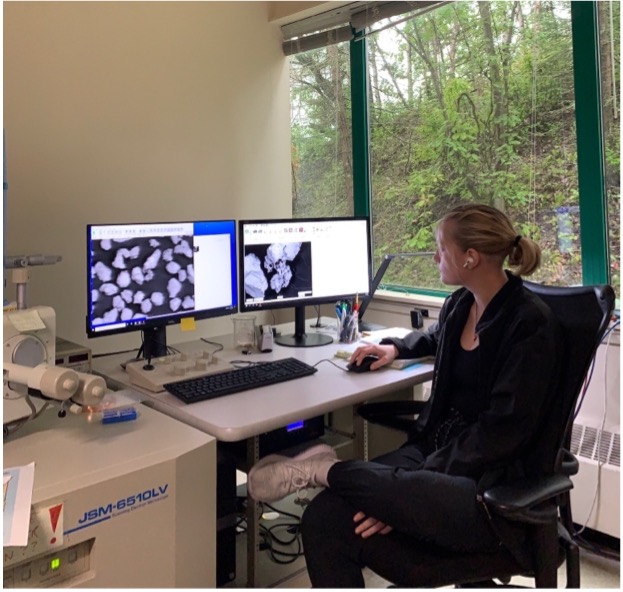

Determined, Kincaid emailed volcano observatories, asking if they needed a lab tech. The Alaska Volcano Observatory said yes, but they could only initially accommodate her as a volunteer. Kincaid worked volunteer day shifts in the lab for months while working a separate night job to pay the bills, on top of her industry position as a marine geologic contractor (Figure 8).

Eventually, the Observatory was able to use Kincaid’s demonstrated productivity to obtain enough federal funding to support her work (Figure 9) until she starts her PhD – which she is excited to begin in the fall of 2023, at a top-ranked research university. Kincaid eagerly looks forward to studying “the geochemistry of Icelandic mantle plumes” under the mentorship of Dr. Tanya Furman.

Part 3: Getting Started with Science Communication

Kincaid first delved into science communication shortly after moving to Florida to start her Geology degree. Classes were in hybrid-form, and she was unable to participate in her pastimes of choice – the gym and aerial acrobatics – since both required groups or public spaces.

“I was bored and I needed a social and creative outlet,” she explained. She also felt “very disconnected” from the LGBTQ+ community, a valued factor of life for Kincaid, the absence of which she felt acutely after moving to a new place amid the pandemic. Unable to make in-person connections in her new city, Kincaid turned to TikTok.

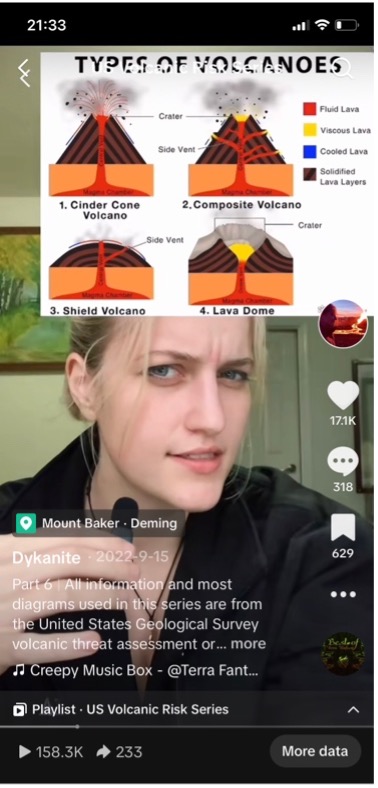

“I started off making exclusively queer-related content,” Kincaid says. After one of her videos went viral, she gained a wave of followers and had a lightbulb moment. “I was like, ‘oh my gosh, I’m gay, and I like geology, and all of these gay people followed me, I bet they would like geology!’” And so began Kincaid’s endeavor to bring geology to life for her growing and increasingly diverse audience.

Kincaid has been asked several times by TikTok viewers why she’s so adamant about being open regarding her sexuality on her geology education channel. Her response?

“I didn’t know that it was possible to be gay and a scientist,” Kincaid says. “Where I grew up, it was very much presented to me that you could either be successful, or you could be gay, like those were mutually exclusive options – especially when it comes to a career that is so networking-oriented.” This idea, she tells me, is one of the main reasons she stayed closeted into her early twenties. “I don’t want other people to have that same experience,” she says. Now she hopes to be the representation for other aspiring scientists that she didn’t have.

Love for teaching and sharing scientific information is nothing new for Kincaid, who has participated in numerous science outreach initiatives. What was new with TikTok was the experience of talking to an audience that often talked back. Kincaid says that this dynamic helped her evolve as a science communicator.

“I was learning how much responsibility there was, in having an audience that big,” she says. Kincaid meticulously cites all of her sources in her videos, and makes sure to reference scientific experts when she discusses research and current events (Figure 10). “The only thing I may be an expert on is… social media science communication,” Kincaid emphasizes. “I don’t really make content that’s my own opinion about scientific things…I am simply translating scientific statements by the actual experts into common language.”

What advice or comments does Kincaid have for current scientists, across fields, about the importance of science communication?

“Ultimately, research is for the public,” Kincaid emphasizes. Lack of access to information, rather than lack of interest – that, she argues, is the real issue.

“What’s happening is that [laypeople] feel excluded from science,” Kincaid says. “[Science] is inaccessible to them, both in how it’s delivered, and in how much it costs.” Building trust, she says, is the key. “We need to communicate [science] to them in a way that they feel they can understand, and in a way that they feel is respectful.”

Part 4: Early-Education Outreach – the Bedrock of Progress

Some of Kincaid’s favorite TikTok engagements are when teachers ask how to get kids excited about geology. It would be easier, she explains to me, if geoscience education was a more widespread requirement in K-12 schools.

“You’re not getting kids at the time where they develop their life dreams,” Kincaid says. She is also keenly aware of the lack of diversity in the geosciences (Figure 11), and points out that racial and socioeconomic inequality contribute to the situation: many resume-building research experiences are un- or under-paid, rendering them inaccessible to those lacking financial support. For Kincaid, all of this just underscores the importance of early-education outreach.

“A lot to do with [kids wanting to study geosciences] is just believing that it’s a possibility for you,” Kincaid says. She hopes to pursue a career as an academic researcher in volcanology, but intends to continue being active in educational outreach.

And why should kids study geology?

“Everything, literally everything, has to do with geology!” Kincaid exclaims. “I feel like it’s kind of… the silent ruler of modern society. Every object in this room with me – and you – right now is a result of minerals and materials that came from the earth.” Global economies, the buildings we construct and occupy, the groundwater we rely upon – all of these, she emphasizes, are based on geology.

“There is a specialty in geology that affects every subset of our society, everything we need to live.” Kincaid ties this notion back to her chosen sub-specialty, volcanology: “Mid-ocean ridges produce a majority of the iron that’s needed by phytoplankton in the oceans, and phytoplankton and algae are the core of oceanic food chains. So, if they don’t have the iron that they can use to photosynthesize… the entire oceanic food web wouldn’t really be able to exist.”

For some reason, it was this image – ocean-floor volcanos producing a crucial element for tiny creatures that anchor the ocean’s ecosystem, the inorganic fueling the organic, the colossal scale and cyclical connections of it all – that drove the message home for me.

“It’s the fundamental basis of our entire planet,” Kincaid says, “it” being geology, and I see it now – and watching her talk about it, I can understand why she flew halfway around the world to walk towards fire in the middle of the night. This is why I – and Kincaid – feel so strongly that science communication, directed from scientists towards a lay audience, is so crucial to the growth and progress of our society: because science helps us understand the world we share, and that knowledge, uncovered by the few, is the rightful inheritance of the many.

Additional information:

- Denali Kincaid’s geology education videos can be found under the name “Dykanite,” an account name combining the words “dyke” – slang for “lesbian” once considered disparaging, but now often reclaimed by members of the queer community – and kyanite, Kincaid’s second-favorite mineral (“because it’s blue!”)

- Her favorite mineral is garnet, because “it’s ortho-rhombic-shaped,” and due to its isotropic properties that cause it to absorb rather than reflect light. “Instead of having a color under a microscope, [garnets] are pitch black… like a little mineral black hole.”

- Her favorite rock, of course, is mid-ocean ridge basalt (MORB) (Figure 12).

TL:DR

- Denali Kincaid – “Dykanite” on TikTok – is a science communicator and aspiring volcanologist whose geology education videos have engaged a vast audience.

- Despite a non-linear career trajectory, Kincaid has found her passion in studying geochemistry and submarine volcanism, and looks forward to starting a PhD on these topics in the fall.

- Kincaid is an enthusiastic science communicator who cares deeply about early-education outreach and the importance of making science accessible to the public.

- Kincaid aspires to be a role model for young people interested in STEM, especially those in the LGBTQ+ community.

References

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-022-04981-x

- https://www.marineinsight.com/environment/what-is-a-mid-ocean-ridge/

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s43247-021-00196-6/figures/1

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41561-018-0116-6

Many thanks to Denali Kincaid, who generously shared her time, her story, and the included images for this article.